A former news reporter has developed an algorithm to help solve murders — but will law enforcement use it?

NOEL CELIS/AFP/Getty Images

A decade or so ago, a Scripps journalist named Thomas Hargrove was after some data for a report on the rate at which U.S. police departments enforced prostitution as a crime. He obtained the data he needed without issue, but a supplementary report that he hadn’t requested showed up, too — perhaps somewhat serendipitously.

The “supplementary homicide report,” Hargrove realized, was a listing of unsolved homicides from cities throughout the United States, and one which U.S. police departments had to submit to the FBI annually. The reporter and self-described “data guy” found the numbers compelling — and devastating.

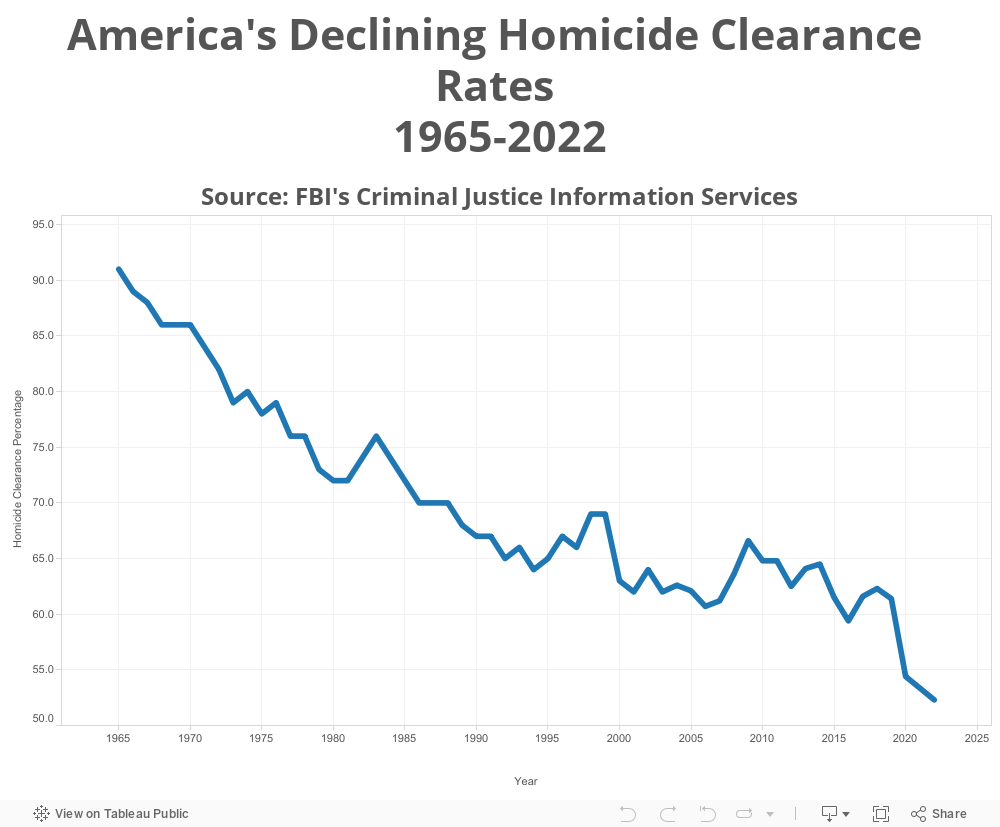

Despite technological advances — whether it be in computer science, medicine and genomics, or any other field that directly lends itself to investigative efforts — the clearance rate (when police make an arrest for a crime, regardless of the outcome) for homicides wasn’t just low; it was falling.

As Hargrove, now 61, studied the overwhelming amount of data, he wondered if there were connections among the unsolved crimes that eluded detectives who had stared at the same cases year after year.

And then Hargrove had an idea: What if he could create a computer algorithm that would do the looking for him? What if he could teach a computer to look for similarities between these unsolved cases?

What if he could teach a computer how to solve a murder?

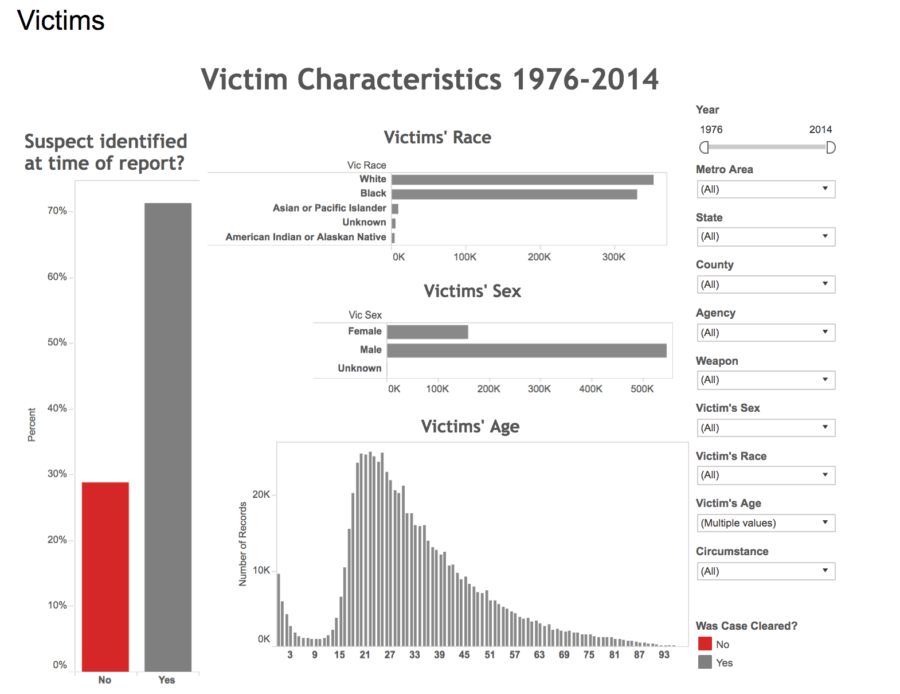

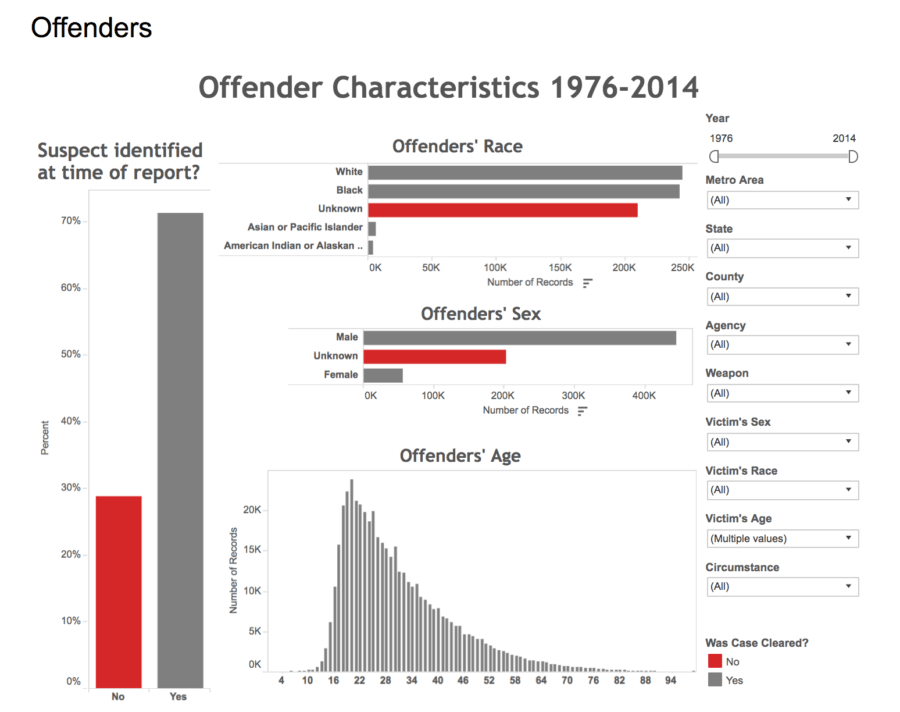

The Supplementary Homicide Report that Hargrove had to work with was from 2002. It included information about 16,000 murders — things like the the victim’s demographics, what killed them and how, and what if anything police knew about the circumstances.

It also contained information on the person who may have committed the crime — that is, if the police department had actually come up with a suspect. Hargrove continued to download the reports each year, working to refine the algorithm he hoped would be able to make connections that the people scouring the cases had missed.

As Hargrove continued to compile the data, he realized that some municipalities weren’t actually sending their reports to the FBI.

“Since it’s inception by Congress in 1930, the Uniform Crime Report has been a completely voluntary program,” Hargrove explains, “[But] It’s our feeling [at the Murder Accountability Project] that reporting murder data (or the other serious crimes) should not be optional. We take the position that the American people have the right to know how they are being murdered, and whether those murders are being solved. We use FOIA laws to compel reporting (to us) the data police did not feel obliged to report under the voluntary UCR.”

With that in mind, Hargrove remained diligent about collecting state data — even if it meant taking individual states to court (which he did with Illinois).

Making use of the Freedom of Information Act, Hargrove gathered additional data on municipal homicides that even the federal government lacked. Hargrove’s compiled information — all of which is available to anyone to download — is the most comprehensive dataset on U.S. homicides available. And since anyone can download it and run it through a statistical analysis program, it could be the basis for a new way to solve murders: by crowdsourcing.

To this end, Hargrove officially founded the Murder Accountability Project in 2015. Everyone involved with the project — and it’s just a handful of people at this point — works on a volunteer basis.

Through their dedication and Hargrove’s follow-through on his big “what if” question, the algorithm he has since developed has proven to be not just effective but essential.

In 2014, for instance, Hargrove’s algorithm identified 15 unsolved strangulation cases in Gary, Indiana, which came along with the arrest of Darren Deon Vann. As it turned out, Vann had been killing women for decades. Officers in Gary dismissed Hargrove’s initial missives about the possibility that the town had a serial killer to contend with — and that came at a cost: According to Hargrove, at least seven women died after he contacted the Gary PD.

The problem isn’t confined to this one Indiana city, either.

“It really is rather abysmal that in 2015, we only solved about 61 percent of murders. That’s ridiculous,” Hargrove said. “So, we’re trying to work with homicide detectives and investigators, offering them a tool that they didn’t have before.”

www.murderdata.org

The Murder Accountability Project has taken its algorithm to the FBI’s Quantico Academy and homicide departments in cities throughout the U.S. The latter may be even more important, as Hargrove points out that the variability in solve-rate amongst cities is staggering.

By teaching detectives how to use the data available, and giving them an efficient tool that is inherently incapable of experiencing fatigue, Hargrove hopes that the project will help lower the rate of unsolved homicides.

That said, the Murder Accountability Project is a non-profit, and when members travel to teach departments about the program, it’s on their own dime.

While Hargrove and project volunteers are dedicated to continuing their work as long as it’s needed, they hope to eventually pass the baton to the state. “Ultimately, our goal is to be put out of business by Congress,” Hargrove says, adding that the work he’s doing really “should be a government function — but nobody’s doing it.”

Well, not nobody: Hargrove certainly is doing the work, and so can you. You can download the data Hargrove uses on the website. If the size of the files (one is 6.8 gigabytes) is any indication, there’s still a lot of work to be done — and some of it might be in your own backyard.

“We would really like it if everybody would call up their local police department’s clearance rate,” Hargrove added, which can be done on the website by inputting a user’s state, county, or agency. “If they don’t like what they see, we hope they’ll have a conversation with their elected leaders to express their feelings about the places where most killers go uncaught.”

Next, read up on the unsolved serial killings that the MAP may be able to solve. Then, read up on six famous people who probably got away with murder and rape.