For nearly two centuries, Australia pursued deliberate policies of extermination against the native people that have left scars visible to this day.

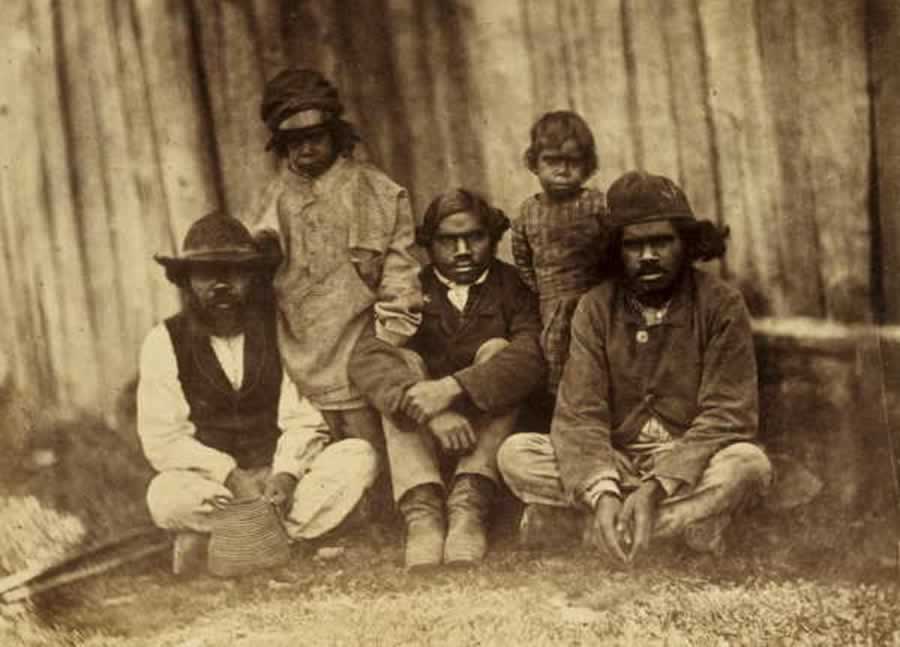

Wikimedia Commons

Writing about the two months he spent in Australia during the around-the-world voyage of the HMS Beagle, Charles Darwin recollected this about what he saw there:

Wherever the European has trod, death seems to pursue the aboriginal. We may look to the wide extent of the Americas, Polynesia, the Cape of Good Hope, and Australia, and we find the same result…

Darwin happened to visit Australia at a bad time. During his 1836 stay, all of the indigenous people of Australia, Tasmania, and New Zealand were in the midst of a catastrophic population crash from which the region has yet to recover. In some cases, such as that of the native Tasmanians, no recovery is possible because they’re all dead.

The immediate causes of this mass death varied. Deliberate killing of native people by Europeans greatly contributed to the decline, as did the spread of measles and smallpox.

Between disease, war, starvation, and conscious policies of kidnapping and re-education of native children, the Australian region’s indigenous population declined from well over a million in 1788 to just a few thousand by the early 20th century.

First Contact, First Casualties

Wikimedia Commons

The first humans we know of arrived in Australia between 40,000 and 60,000 years ago. That is an immense amount of time – at the upper end, it’s ten times longer than we’ve been farming wheat – and we know next to nothing about the bulk of it. Early Australians were preliterate, so they never wrote anything down, and their cave art is cryptic.

We do know that the land they traveled to was extremely harsh. Highly unpredictable seasons have always made Australia hard to live in, and during the last ice age huge carnivorous reptiles, including a monitor lizard the size of a crocodile, inhabited the continent. Giant man-eating eagles flew overhead, venomous spiders scurried underfoot, and clever humans took the wilderness head on and won.

By the time British explorer James Cook’s expedition reached Australia in 1770, over a million people – virtually all descendants of those first pioneers – lived in almost complete isolation, just as their ancestors had for a thousand generations.

The consequences of breaking this airlock were immediate and devastating.

In 1789, an outbreak of smallpox nearly wiped out the indigenous people living in what is now Sydney. The contagion spread outward from there and destroyed whole bands of Aborigines, many of whom had never seen a European.

Other diseases followed; in turn, the native population was decimated by measles, typhus, cholera, and even the common cold, which had never existed in Australia before the first Europeans came along and started sneezing on things.

Without an ancestral history of coping with these pathogens, and with only traditional medicine to treat the sick, the indigenous Australians could only stand by and watch as plagues consumed their people.

The Press for Land

Wikimedia CommonsFarmland near Bruce Rock in the Western Australian wheat belt.

With the first large tracts of land cleared by disease, the London-based planners thought Australia seemed like an easy spot to colonize. A few years after the First Fleet dropped anchor, Britain established a penal colony at Botany Bay and started shipping convicts to farm the land there.

Australia’s soil is deceptively fertile; the first farms sprouted bumper crops right away and kept on producing good harvests for years. Unlike European or American soil, however, Australia’s farmland is only rich because it had tens of thousands of years to stockpile nutrients.

The land’s geological stability means there’s very little upheaval in Australia, so very few fresh nutrients get deposited in the dirt to support long-term agriculture. The bounteous harvests of the first years, therefore, were effectively gotten by mining the soil of non-renewable resources.

When the first farms gave out, and when colonists first introduced sheep to graze the wild grasses, it became necessary to spread out and cultivate new land.

As it happens, the children of those who survived the first epidemics occupied the land. Because they had a low population density – partly because of their hunter-gatherer lifestyle, and partly because of the plagues – none of these Stone Age nomads were in a position to resist settlers and ranchers with horses, guns, and British soldiers for backup.

As such, countless Aborigines fled land that their ancestors may have inhabited for thousands of years, and colonists simply shot numberless tens of thousands others to keep them from hunting sheep or stealing crops.

No one knows how many Australian natives died in this way. While the Aborigines had no way to keep records of the killing, the Europeans seem not to have bothered: Shooting an “abo” became so routine that accurate records are impossible to come by, but the death toll must have been immense as vast new tracts of land opened up to replace exhausted soil every few harvest cycles.