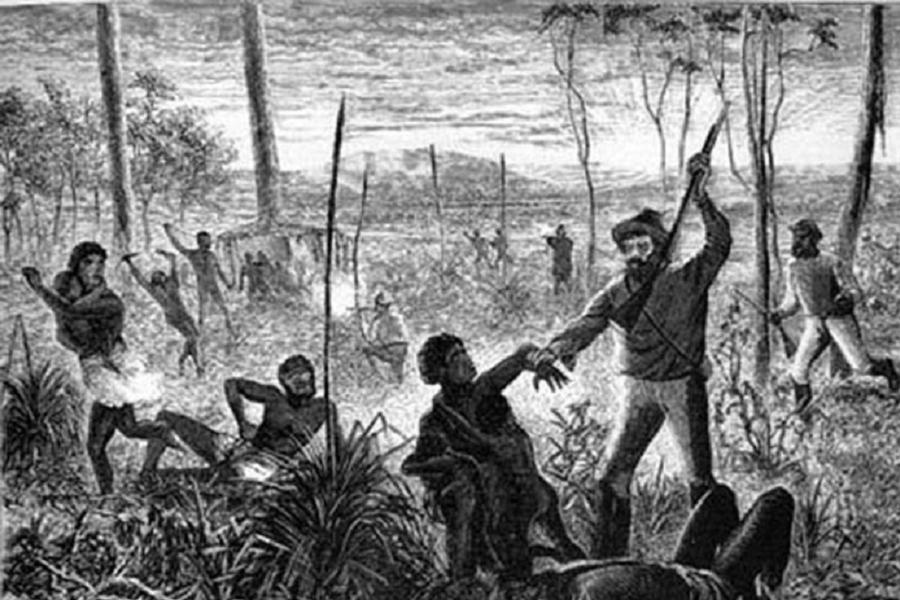

Hunting for Sport

Wikimedia Commons

In some ways, differing understandings of property can help explain the ranchers’ slaughtering of natives. Colonists complained about traditional hunters poaching sheep that didn’t “belong” to them, and often had other property taken by natives who didn’t grow up with the same ideas about property rights that the English-speaking whites took for granted.

These losses cost the ranchers and farmers dearly and impaired the new colony’s growth, so the authorities eventually decided to let one problem solve another in perhaps the most grotesque way possible: bounty hunting.

In 1833, the Noongar tribe from south of modern-day Perth rose in a minor revolt. They mostly limited their resistance to spearing sheep, which did not amuse the territorial government.

The government placed a £30 bounty on a tribal elder named Yagan, whom settler William Keates eventually ran to the ground. Soon enough, Yagan’s pickled head made its way to London as a curiosity, where it remained until 1997.

This bounty method turned out to be popular and effective. In the early 1830s, governments across the colony offered bounties of £5 per aboriginal adult and £2 per child. By the middle of the decade, it was open season on the native people.

In a single action in 1832, over 5,000 whites formed a human chain in Van Diemen’s Land and drove through the bush as if they were a hunting party. Colonists forced Aborigines who escaped the drive to Flinders Island, where scarcity and disease nearly drove them extinct.

The Lost Generations

National Unity Government

This carnage eventually got to be a bit much for the British government, which had undergone a radical shift with the incoming Whig Party. These reformers got elected on a platform of abolishing slavery and limiting various other outrages in the colonies, as well as enacting major reforms at home. The new climate opposed open-air murder, and London started putting pressure on Australia to rein things in a bit.

In response, the Australian government actually charged a handful of whites with murder in the 1838 Stockman Case, which the Crown instigated after a dozen stock ranchers staged an unprovoked attack on a nearby camp of Aborigines. This marked the first time the state had formally charged whites for killing natives, and the whole colony watched to see how it would turn out.

When the court found the men guilty – and worse, sentenced some to hang – the settler population across Australia unfurled in outrage. Many protested and sent letters repudiating the decision, but they didn’t save the condemned men.

Still, the event marked a sea change in the way colonists treated native people. Going forward, the destruction of the native way of life would be far more appropriate for the papers back home — like assimilation.

The Crown government came up with a series of reforms aimed at civilizing the Aborigines. In the past, the native people could come and go as they liked, though at the risk of being shot on sight if they stepped out of line.

Under the new order, from about 1838 onward, they held a legal status akin to children. The Crown established a royal office for Aboriginal affairs, which assigned each group to a specific geographic area and issued permits for travel.

Commissions would approve marriages, along with job assignments and housing arrangements. The government assigned England-trained missionaries to each group to Christianize them. Likewise, colonial governments would routinely remove Aboriginal children from their parents and force them into schools to learn English, with severe punishments for speaking native languages.

The children had to dress, eat, live, and work like white children, which a regimen of physical punishment enforced. On top of the official abuse, the consequence-free environment of these schools invited rampant physical and sexual abuse that went almost totally unnoticed and unaddressed for decades.

By 1920, the children forced into these schools had become known as the “Stolen Generations.”

Much of the culture was lost as well. In 1905, for example, Fanny Cochrane Smith, the last full-blooded native Tasmanian and descendant of a group that had been isolated even from other Aborigines for 10,000 years, died shortly after pressing a wax cylinder of traditional songs. It is the only audio recording of the Tasmanian language in existence.