Cetacean intelligence is an object of fascination among scientists. Their social complexity and methods of communications rival, or even outmatch, our own.

Before we delve into the meat of this issue, here are a couple of terms to familiarize yourself with.

Cetacean: the term “Cetacean” refers to the order of marine mammals ranging from the 200-ton blue whale, to the comparatively tiny 130-pound harbor porpoise, and everything in-between. Cetacea can be divided into two categories: toothed whales, whose best known members include dolphins, porpoises, narwhals, and orcas, and baleen whales like the humpback whale, right whale, and grey whale.

It doesn’t matter that you can’t read the species names. Just know that there are A LOT of different kinds of cetacea.

Frontiers Of Zoology

Smarter: words like “intelligent” and “smart” are inherently loaded terms. They’re typically used to refer to human developments and achievements, and trying to measure another creature’s abilities against a human barometer of intelligence is as futile as it is reductive. Cetacea don’t take IQ tests, but they do recognize themselves, other whales, and individual humans. A dolphin has obviously never graduated from college or held political office, but some of the more social species have highly developed languages that make English seem simple.

Beluga whales are small, playful, toothed whales.

Adventure Caravans

Why Should You Care If You’re Smarter Than A Cetacean?

There’s currently a debate about whether whales and dolphins should hold a status called non-human personhood. If this legislation were to pass it would give cetaceans individual rights and “moral standing,” and thus becoming “ethically indefensible to kill, injure, or keep these beings captive for human purposes.” They wouldn’t be able to vote, so don’t worry, but it would force governments to protect whales and dolphins from the slaughter and abuse they so regularly face in the wild and captivity.

Herein lies the problem–how do we measure the intelligence of creatures we can’t communicate with? One method scientists have used is measuring brain size. If size is the standard we’re going with, then at 8,000 cubic centimeters the sperm whale’s brain is the largest in the animal kingdom.

But that’s a highly reductive method that fails to take overall body size into account, you say. It’s almost as misleading as phrenology, you say. You’re not wrong. Plus, where are we getting all these whale brains? Craigslist? And if we do measure brain-to-body mass, then the tree shrew is the winner holding a whopping 10% of its body mass in its brain. That’s not helpful, and the question remains: are you smarter than a cetacean?

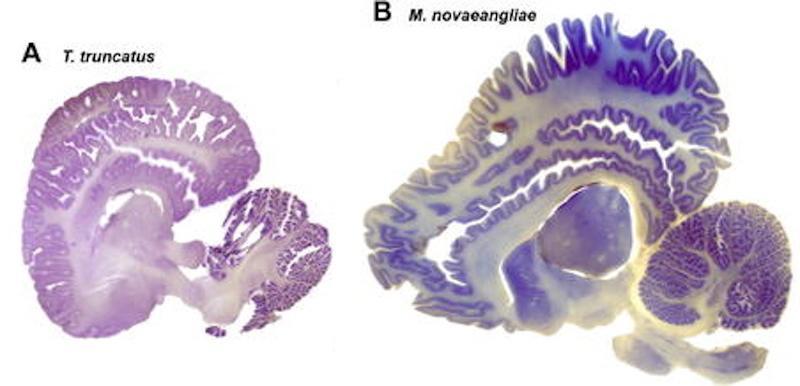

So simply measuring the size of a brain doesn’t work, and measuring brain-to-body mass doesn’t work, but maybe brain scans can help us understand cetacean intelligence.

Neuroscientist Lori Marino believes cetaceans (especially toothed whales) are so smart because their need to hunt as a group has encouraged them to develop social complexity and methods of communication which rival, or even outmatch our own. Baleen whales survive off of easy-to-find plankton and krill, so their brains aren’t as complex as their toothed relations.

A dolphin’s brain (left) and a humpback whale’s brain (right). Cetacean brains have far more more cortical convolutions and surface area than human brains do.

Neurotic Thought

Marino took MRI scans of a group of orcas, and the results were incredible. Their limbic system (the area of a mammal’s brain which processes emotions) has an entire component that humans, and most other mammals, lack. Orcas distribute their sense of self throughout their entire pod, which means it’s not an orca’s nature to disconnect from his/her social group in the same way humans often do for survival or success.

The distributed sense of self would explain mass strandings–a previously inexplicable phenomena where a pod of a hundred or more individuals will beach themselves on shore to die when only one is sick. It would also explain why when a mother orca dies, her male calf will often stop eating, go into a clinical depression, and die.

Mass stranding in Flinders Bay, Australia.

Wikipedia

Their behavior implies a social cohesion unlike anything humans have ever experienced, and Marino concluded cetaceans have “highly elaborate emotional lives [which are] stronger and more complex than in humans.” So maybe we can say that they have a different kind of intelligence–an empathetic intelligence that makes us look unevolved by comparison. But until we develop the technology to untangle their languages we’ll have to go off inferences and educated guesses.

Bottom line:

We have no idea whether or not you’re smarter than a cetacean — which would truly be a weird pet to own. The world isn’t black and white. Deal with it.