How a single photo by a photography student of David Kirby moved the world to a greater understanding of the AIDS pandemic.

Therese FrareDavid Kirby, near death, lies in bed with his family by his side in Ohio, 1990.

In November 1990, a gaunt, dying man appeared in the pages of LIFE magazine.

That man, David Kirby, had already made a name for himself as an HIV/AIDS activist in the 1980s, and was in the final stages of the disease in March 1990, when journalism student Therese Frare began photographing Kirby’s own battle with the virus.

The following month, Frare captured Kirby on his deathbed surrounded by his family. He died soon after it was taken, and his family’s grief came through the haunting black-and-white still frame.

The photo took on a life of its own after being published, and the story surrounding it is as moving as the image itself.

David Kirby The Activist

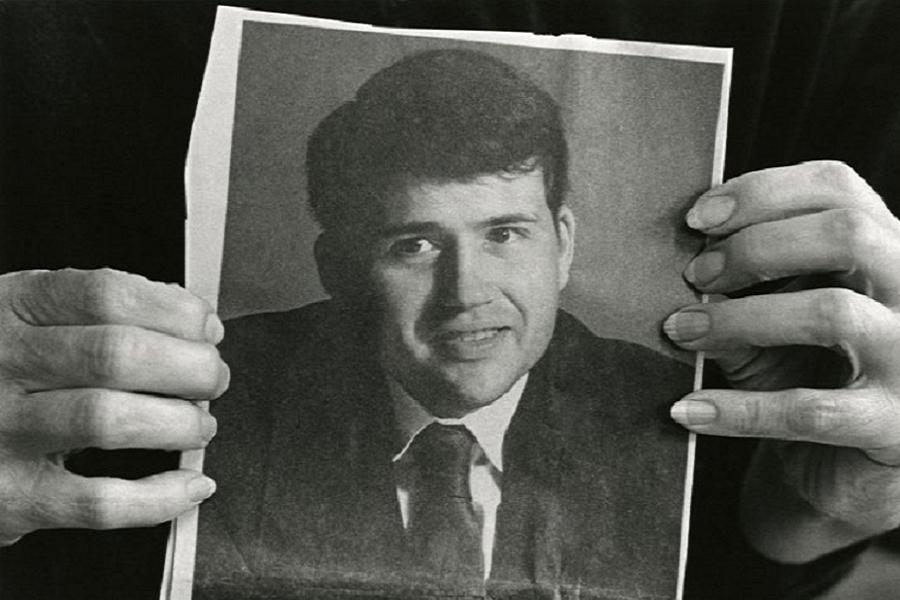

Therese FrareDavid Kirby’s mother holds a picture of him from about ten years before his death, when he was a healthy young man.

David Kirby was born in 1957 and raised in a small town in Ohio. As a gay teenager in the 1970s, he found life in the Midwest difficult.

After finding out about his orientation, Kirby’s family reacted the way most did then: negatively. With his personal relationships strained and no obvious way forward for him, Kirby set off for the West Coast and settled into life in the (still partly underground) gay scene in Los Angeles. He fit in well there and soon became a gay activist.

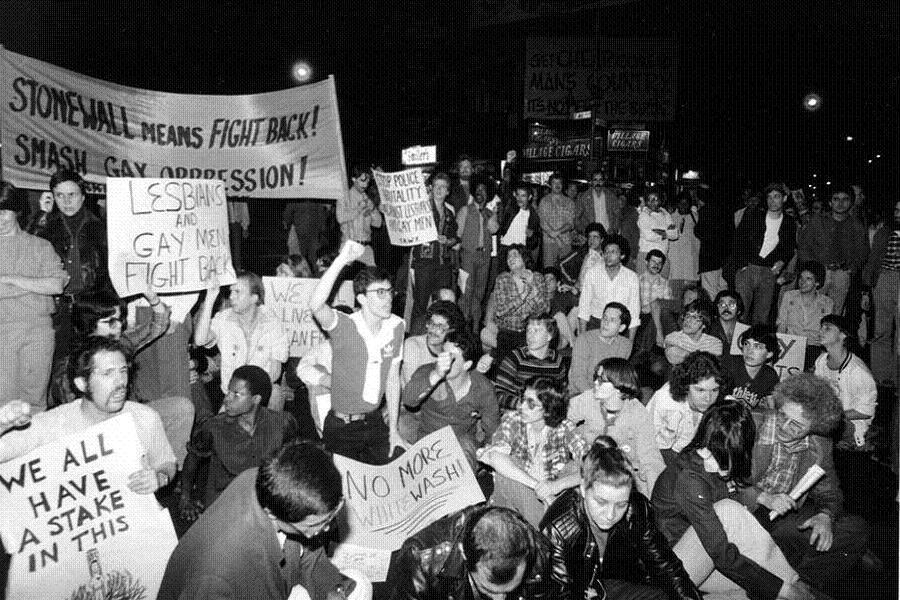

In the 1970s and ’80s, homosexual behavior was still illegal in most states. Normal adult relationships for gays carried the risk of arrest and prosecution as sex offenders.

In California, in 1978, the so-called Briggs Initiative, for example, had sought to ban openly gay residents from working near children in a public school. Activists had been crucial in the initiative’s narrow defeat, and Kirby began attending rallies and protests to widen gay rights in the state and nationwide.

As activists tend to do, Kirby built up a network of contacts who would later help him raise awareness of the disease that was stalking his community.

Tremors Of The Epidemic

Wikimedia CommonsThe 1970s were a time of increasing social and political consciousness for the gay community.

Unfortunately for David Kirby, and for millions of others, the Los Angeles gay scene was an epicenter of the burgeoning HIV/AIDS epidemic. The first scientific description of what we now call AIDS was published as a series of case studies of Los Angeles residents who were treated at the UCLA Medical Center.

Kirby got to town just as the infection was taking off, but before anybody knew what was going on.

It was typical of gay men in “the scene” to have multiple partners in quick succession, and protection was almost never used. Combined with its long incubation period and slow, enigmatic onset, the disease was well-positioned to spread from person to person with impunity.

Nobody knows when Kirby was infected, but by the early 1980s, clusters of unusual cancers and respiratory illnesses were cropping up among gay men in every major city in America.

Kirby was diagnosed with AIDS in 1987 at the age of 29. Without effective treatments or even a clear idea of how the virus was killing its victims, the diagnosis was a death sentence. It was known by then that the infected had from a few months to a couple of years after the onset of symptoms to live.

Kirby decided to spend the time he had left in AIDS activism. He also reached out to his family and asked to come home.