Over the course of 100 days in 1994, the Rwandan Genocide of Hutus against Tutsis claimed the lives of some 800,000 people — while the world sat by and watched.

Over the course of 100 days in 1994, the central African nation of Rwanda witnessed a genocide that was shocking for both the sheer number of its victims and the brutality with which it was conducted.

An estimated 800,000 men, women, and children (more than 1 million by some estimates) were hacked to death with machetes, had their skulls bashed in with blunt objects, or were burned alive. Most were left to rot where they fell, leaving nightmarish mountains of dead preserved in their last moments of agony throughout the country.

For a period of three months, nearly 300 Rwandans were killed every hour by other Rwandans, including former friends and neighbors — in some cases, even family members turned on each other.

And as an entire country was consumed with horrific bloodshed, the rest of the world stood idly by and watched, either woefully ignorant of the Rwandan Genocide, or worse, purposefully ignoring it — a legacy that, in some ways, persists to this day.

The Seeds Of Violence

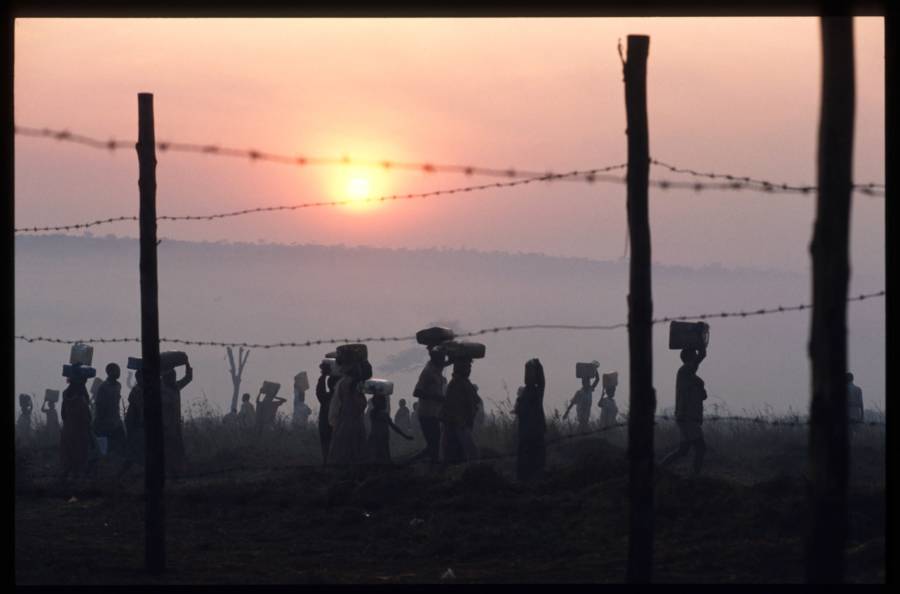

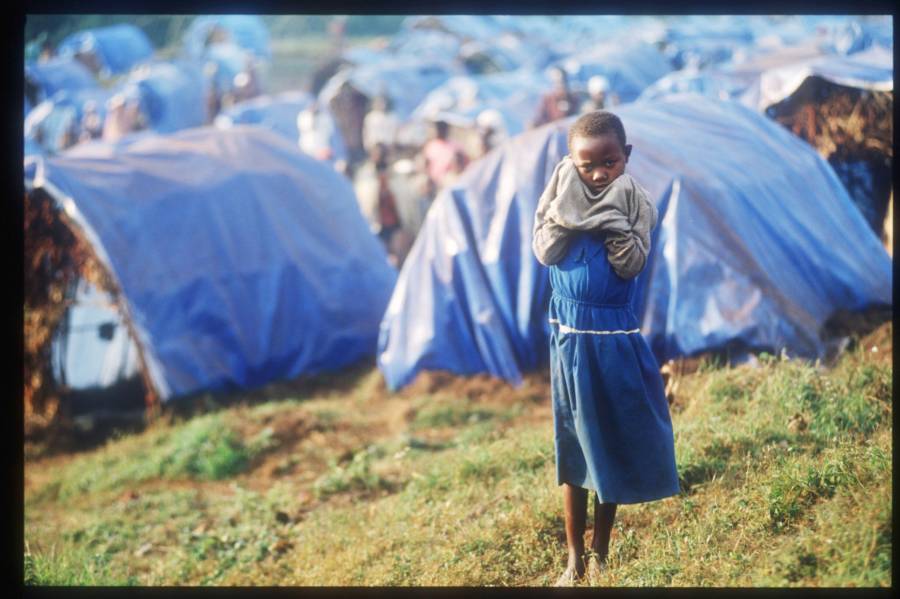

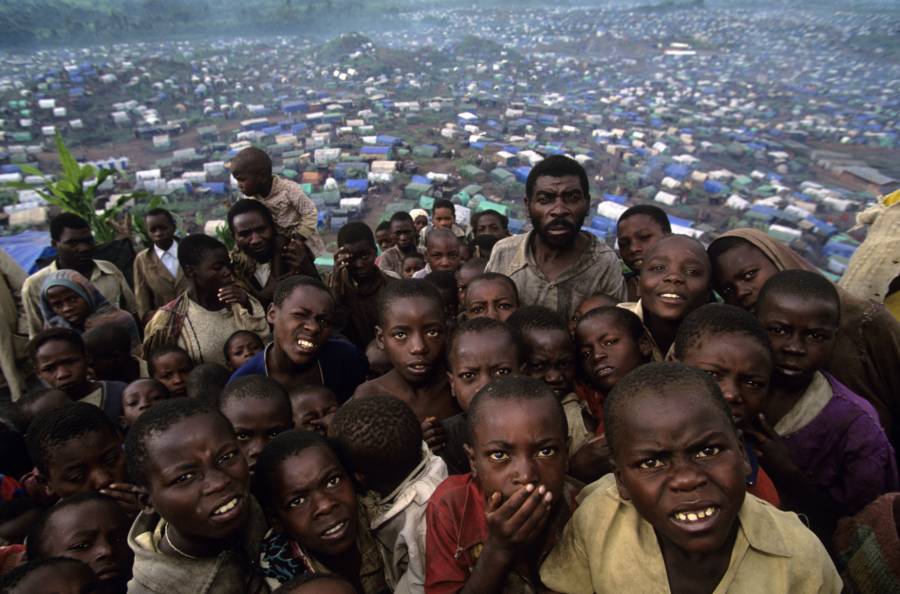

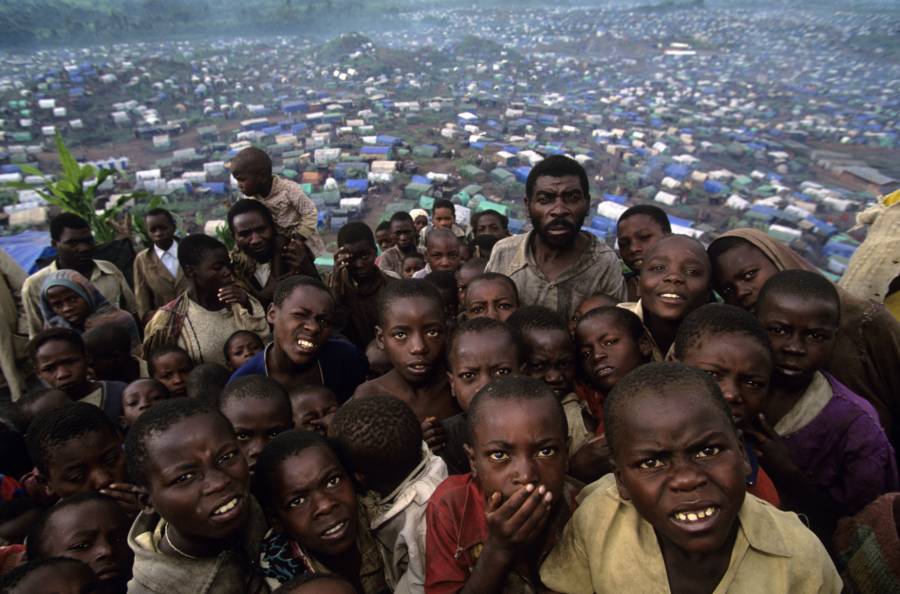

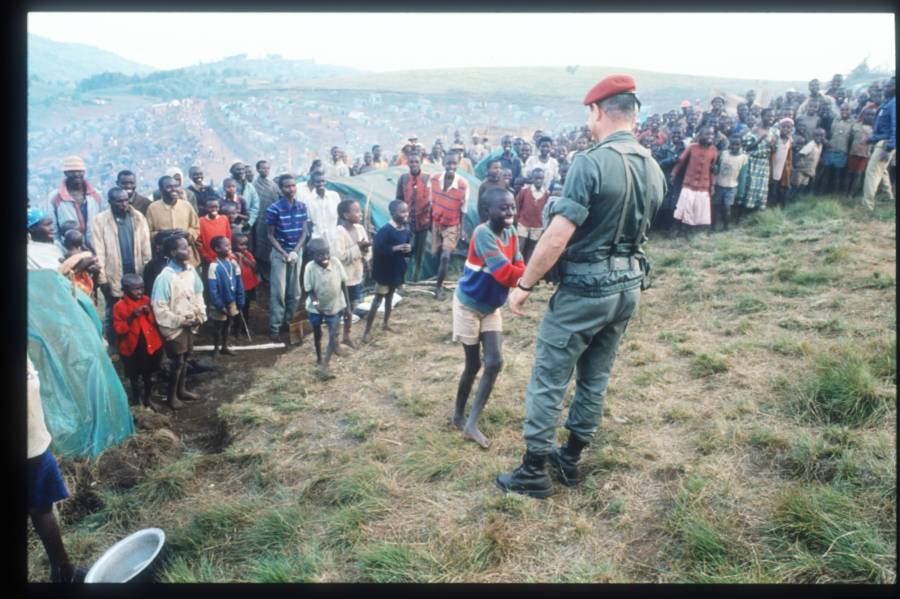

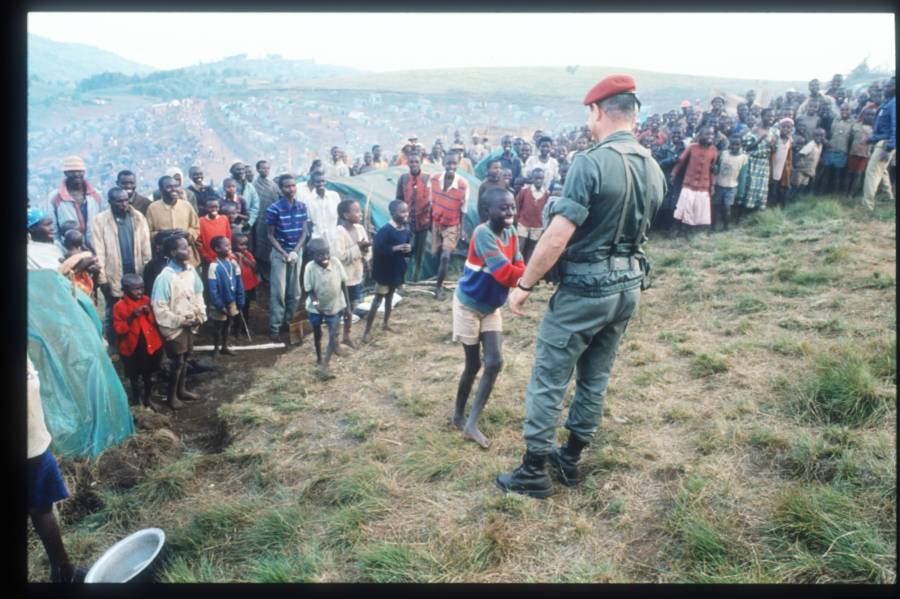

Joe McNally/Getty ImagesRefugees of the Rwandan Genocide stand atop a hill near hundreds of makeshift homes in Zaire in Dec. 1996.

The first seeds of the Rwandan Genocide were planted when German colonialists took control of the country in 1890.

When Belgian colonialists took over in 1916, they forced Rwandans to carry identification cards listing their ethnicity. Every Rwandan was either a Hutu or a Tutsi. They were forced to carry those labels with them everywhere they went, a constant reminder of a line drawn between them and their neighbors.

The words “Hutu” and “Tutsi” had been around long before the Europeans arrived, though their exact origins remain unclear. That said, many believe that the Hutus migrated to the region first, several thousand years ago, and lived as an agricultural people. Then, the Tutsis arrived (presumably from Ethiopia) several hundred years ago and lived more as cattle-herders.

Soon, an economic distinction arose, with the minority Tutsis finding themselves in positions of wealth and power and the majority Hutus more often subsisting in their agricultural lifestyle. And when the Belgians took over, they gave preference to the Tutsi elite, putting them in positions of power and influence.

Before colonialism, a Hutu could work his way up to join the elite. But under Belgian rule, the Hutus and the Tutsis became two separate races, labels written in the skin that could never be peeled off.

In 1959, 26 years after the identity cards were introduced, the Hutus launched a violent revolution, chasing hundreds of thousands of Tutsis out of the country.

The Belgians left the country shortly after in 1962, and granted independence to Rwanda — but the damage had already been done. The country, now ruled by Hutus, had been turned into an ethnic battleground where the two sides stared each other down, waiting for the other to attack.

The Tutsis who'd been forced out fought back several times, most notably in 1990, when the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) — a militia of Tutsis exiles led by Paul Kagame with a grudge against the government — invaded the country from Uganda and tried to take the country back. The ensuing civil war lasted until 1993, when Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana (a Hutu) signed a power-sharing agreement with the majority-Tutsi opposition. However, the peace didn't last long.

On April 6, 1994, a plane carrying Habyarimana was blasted out of the sky with a surface-to-air missile. Within minutes, rumors were spreading, pinning the blame on the RPF (who exactly is responsible remains unclear to this day).

The Hutus demanded revenge. Even as Kagame insisted that he and his men had had nothing to do with Habyarimana’s death, furious voices were filling the radio waves, ordering every Hutu to pick up any weapons they could find and make the Tutsi pay in blood.

“Begin your work,” one Hutu army lieutenant told mobs of furious Hutus. “Spare no one. Not even babies.”

The Rwandan Genocide Begins

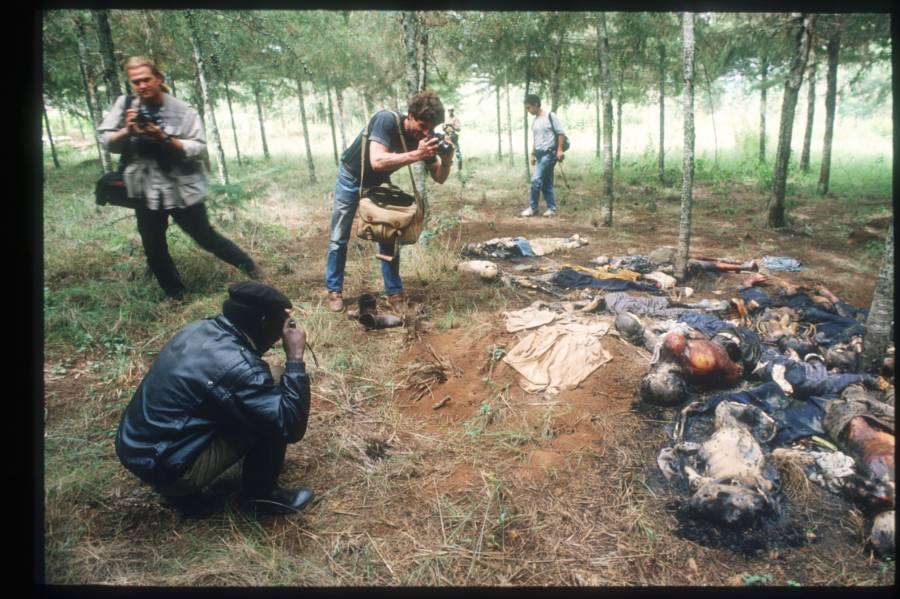

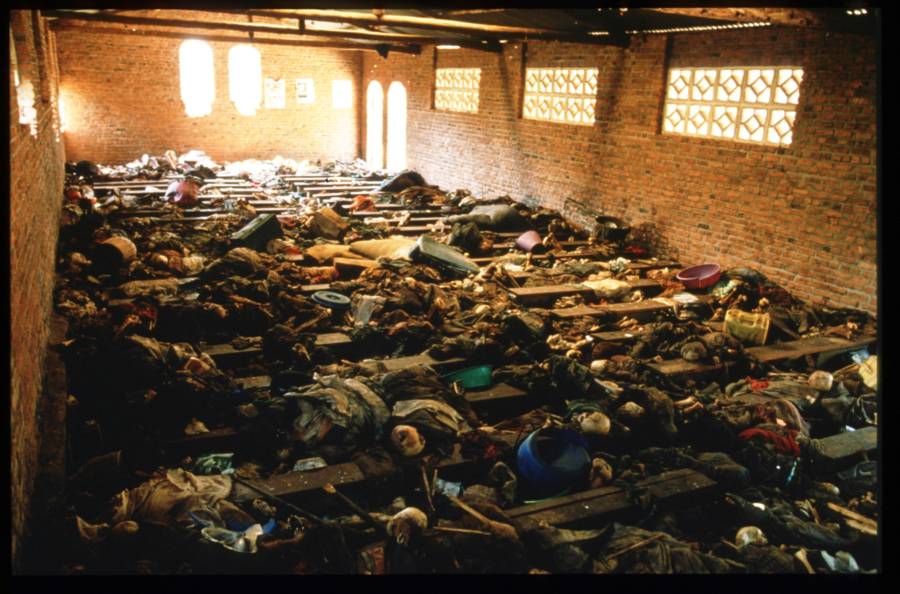

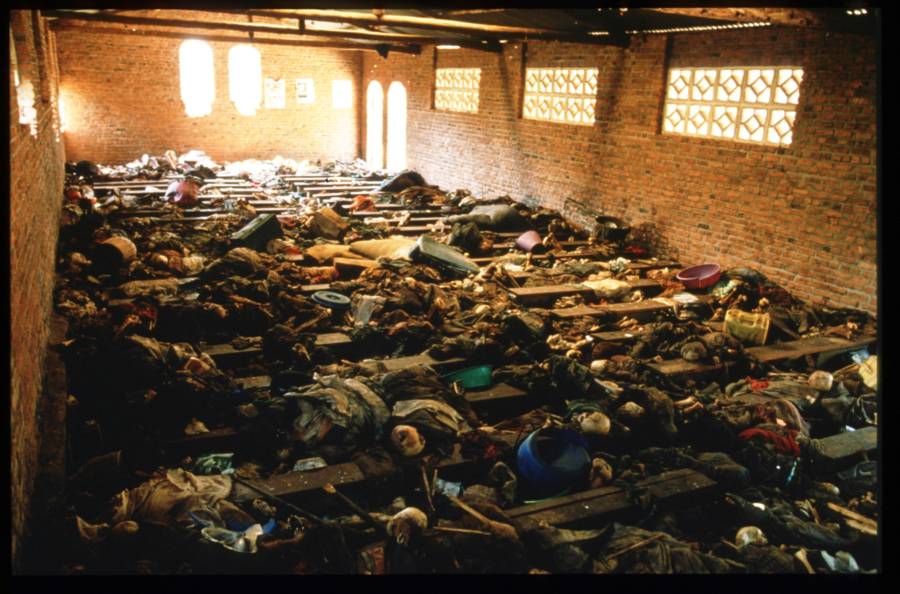

Scott Peterson/Liaison/Getty ImagesThe bodies of 400 Tutsis murdered by Hutu militiamen during the Rwandan Genocide were found in a church at Ntarama by an Australian-led United Nations team.

The Rwandan Genocide began within an hour of the plane going down. And the killings wouldn't stop for the next 100 days.

Extremist Hutus quickly took control of the capital city of Kigali. From there, they began a vicious propaganda campaign, urging Hutus across the country to murder their Tutsi neighbors, friends, and family members in cold blood.

Tutsis quickly learned that their government would not protect them. The mayor of one town told the crowd begging him for help:

"If you go back home, you shall be killed. If you escape into the bush, you shall be killed. If you stay here, you shall be killed. Nevertheless, you must leave here, because I do not want any blood in front of my town hall.”

At the time, Rwandans still carried identity cards listing their ethnicity. This relic from colonial rule made it all the easier for the slaughter to be carried out. Hutu militiamen would set up roadblocks, check the identity cards of anyone trying to pass, and viciously cut down anyone bearing the ethnicity "Tutsi" on their cards with machetes.

Even those who sought refuge in places they thought they could trust, like churches and missions, were slaughtered. Moderate Hutus were even slaughtered for not being vicious enough.

"Either you took part in the massacres," one survivor explained, "or you were massacred yourself."

The Ntarama Church Massacre

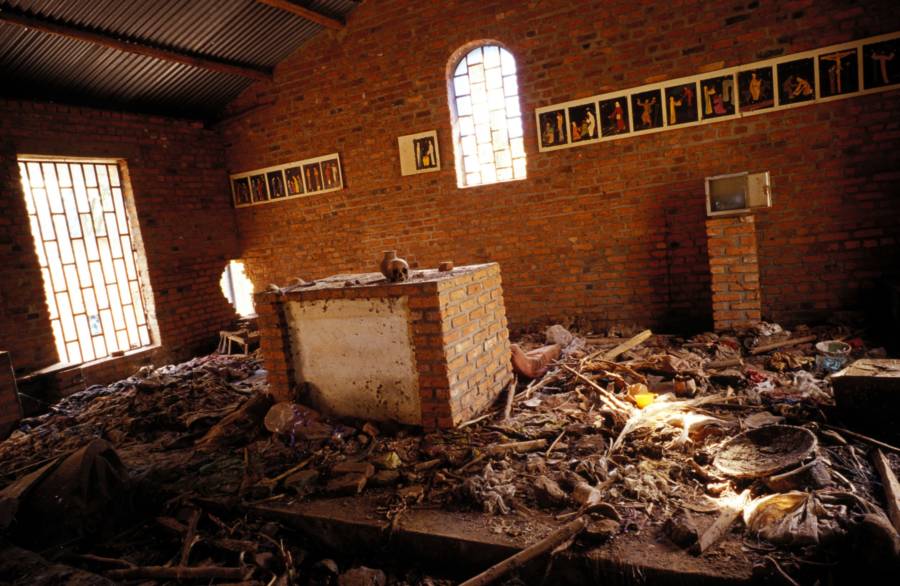

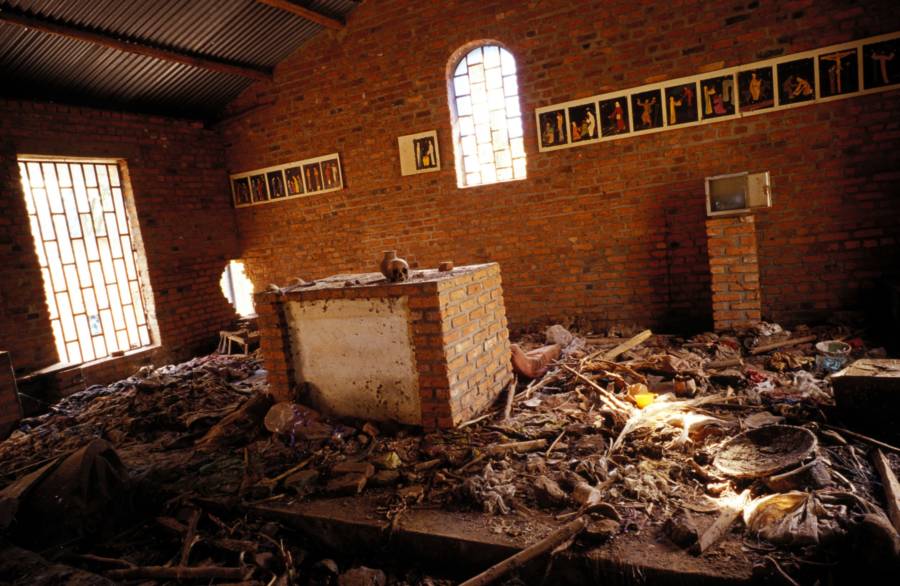

Per-Anders Pettersson/Getty ImagesThe floor of Ntarama church — where thousands of people were killed during the Rwandan Genocide — is still littered by bones, clothes, and personal belongings.

Francine Niyitegeka, a survivor of the massacre, recalled how after the Rwandan Genocide began, she and her family planned "to stay in the church in Ntarama because they had never been known to kill families in churches."

Her family's faith was misplaced. The church in Ntarama was the scene of one of the worst massacres of the entire genocide.

On April 15, 1994, Hutu militants blasted open the church doors and began hacking away at the crowd gathered inside. Niyitegeka remembered when the killers first entered. The frenzy was such that she couldn't even perceive every individual murder, but that she "recognised many neighbours’ faces as they killed with all their might."

Another survivor recalled how his neighbor shouted that she was pregnant, hoping the assailants would spare her and her child. Instead one of the assailants "ripped open her belly like a pouch in one slicing movement with his knife."

At the end of the Ntarama Massacre, an estimated 20,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus were dead. The bodies were left out right where they fell.

When photographer David Guttenfelder came to take pictures of the church a few months after the massacre, he was horrified to discover "people piled on top of one another, four or five deep, on top of the pews, between the pews, everywhere," most of whom had been struck down by people with whom they had lived and worked.

Over the course of several months, the Rwandan Genocide played out in horrific incidents like this. In the end, an estimated 500,000 - 1 million people were killed, with untold numbers likely in the hundreds of thousands raped as well.

The International Response

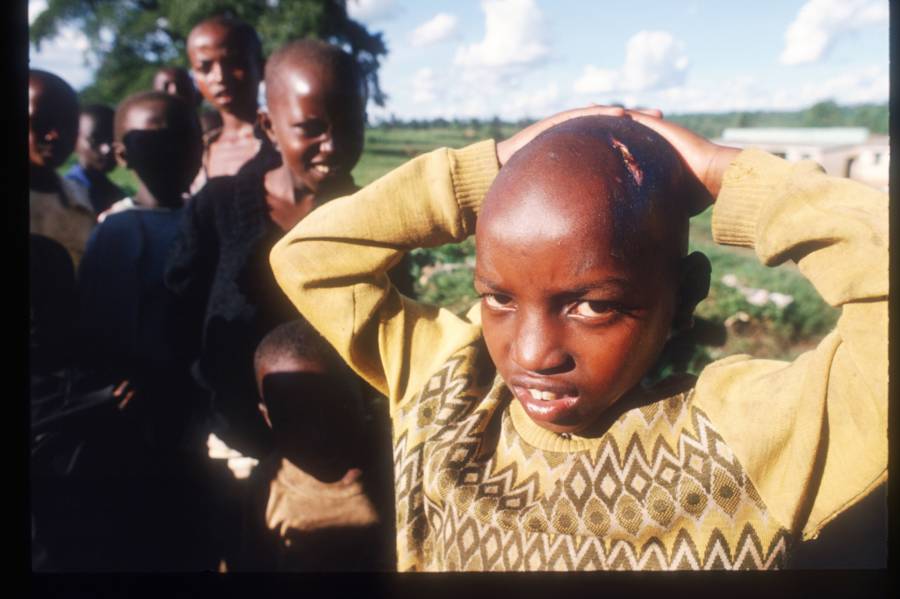

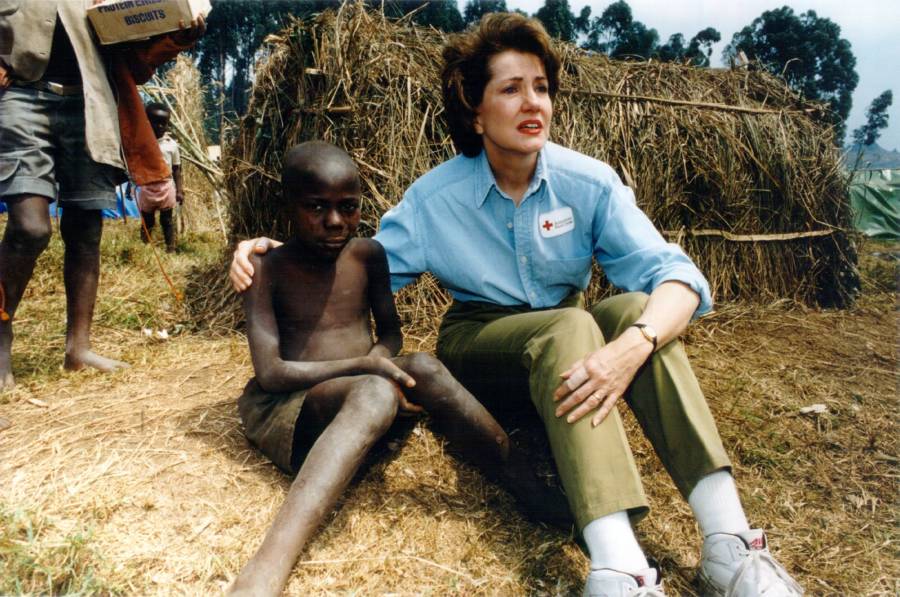

Scott Peterson/Liaison/Getty ImagesA French soldier gives candy to a Tutsi child at the Nyarushishi Tutsi refugee camp on the Zaire border in Gisenyi, Rwanda. June 1994.

Hundreds of thousands of Rwandans were being slaughtered by their friends and neighbors — many coming from either the army or government-backed militias like the Interahamwe and Impuzamugamb — but their plight was largely ignored by the rest of the world.

The United Nations' actions during the Rwandan Genocide remain controversial to this day, especially considering that they had received previous warnings from personnel on the ground that the risk of genocide was imminent.

Although the UN had launched a peacekeeping mission in the fall of 1993, the troops were forbidden from using military force. Even when the violence kicked off in the spring of 1994 and 10 Belgians were killed in the initial attacks, the UN decided to withdraw its peacekeepers.

Individual countries were also unwilling to intervene in the conflict. The U.S. was hesitant to contribute any soldiers after a failed 1993 joint peacekeeping mission with the UN in Somalia left 18 American soldiers and hundreds of civilians dead.

Rwanda's former colonizers, the Belgians, withdrew all of their troops from the country immediately after the murder of its 10 soldiers at the start of the Rwandan Genocide. The withdrawal of European troops only emboldened the extremists.

The Belgian commanding officer in Rwanda later admitted:

"We were perfectly aware of what was about to happen. Our mission was a tragic failure. Everyone considered it a form of desertion. Pulling out under such circumstances was an act of total cowardice."

A group of around 2,000 Tutsis who had taken shelter at a school guarded by UN troops in the capital of Kigali watched helplessly as their last line of defense abandoned them. One survivor recalled:

"We knew the UN was abandoning us. We cried for them not to leave. Some people even begged for the Belgians to kill them because a bullet would be better than a machete."

The troops continued their withdrawal. Mere hours after the last of them had left, most of the 2,000 Rwandans seeking their protection were dead.

Finally, France requested and received approval from the UN to send their own troops to Rwanda in June of 1994. The safe zones established by French soldiers saved thousands of Tutsi lives — but they also allowed Hutu perpetrators to slip over the border and escape once order had been re-established.

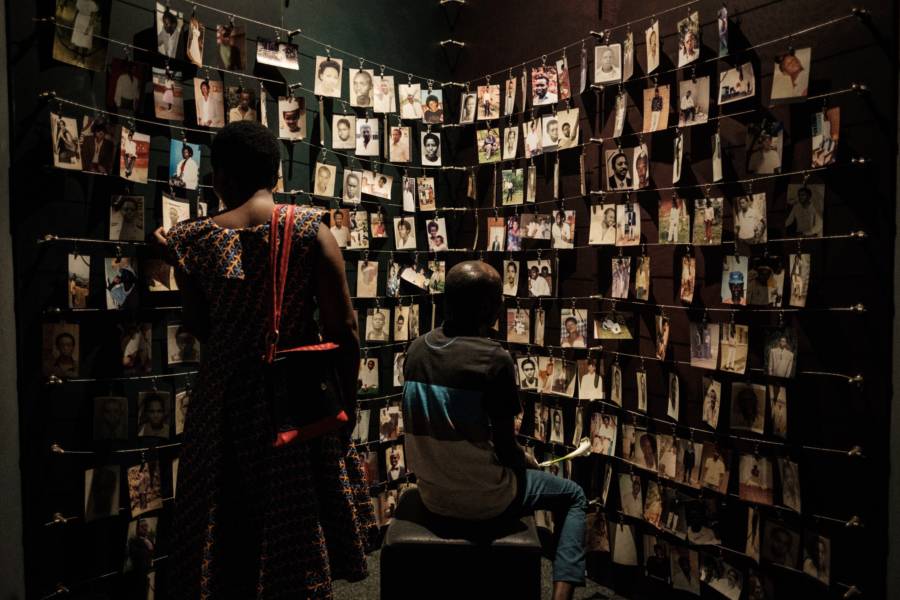

Forgiveness In The Wake Of A Massacre

MARCO LONGARI/AFP/Getty ImagesA survivor of the Rwandan Genocide is taken away by family members and a policeman in Butare's stadium, where more than 2,000 prisoners suspected of taking part in the genocide were made to face the victims of the massacre. Sept. 2002.

The violence of the Rwandan Genocide came to an end only after the RPF was able to wrest control of most of the country away from the Hutus in July 1994. The death toll after just three months of fighting was close to 1 million Rwandans, both Tutsis and moderate Hutus who stood in the way of the extremists.

Fearing reprisal from the Tutsis who were once again in power at genocide's end, more than 2 million Hutus fled the country, with most winding up in refugee camps in Tanzania and Zaire (now the Congo). Many of the most-wanted perpetrators were able to slip out of Rwanda, and some of those most responsible were never brought to justice.

Blood was on nearly everyone's hands. It was impossible to imprison every Hutu who had killed a neighbor. Instead, in the wake of the genocide, the people of Rwanda had to find a way to live side-by-side with those who had murdered their families.

Many Rwandans embraced the traditional concept of "Gacaca," a community-based justice system which forced those who had participated in the genocide to ask forgiveness from the families of their victims face-to-face.

The Gacaca system has been hailed by some as a success that allowed the country to move forward rather than linger in the horrors of the past. As one survivor said:

"Sometimes justice does not give someone a satisfactory answer... But when it comes to forgiveness willingly granted, one is satisfied once and for all. When someone is full of anger, he can lose his mind. But when I granted forgiveness, I felt my mind at rest."

Otherwise, the government prosecuted some 3,000 perpetrators in the ensuing years, with an international tribunal also going after lower-level offenders. But, all in all, a crime of this magnitude was simply too vast to fully prosecute.

Rwanda: A Nation In Healing

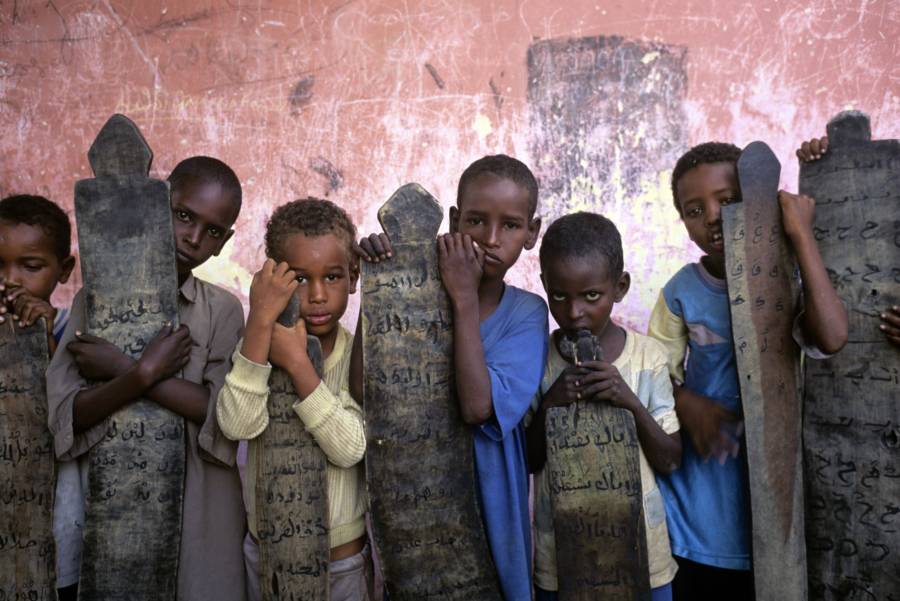

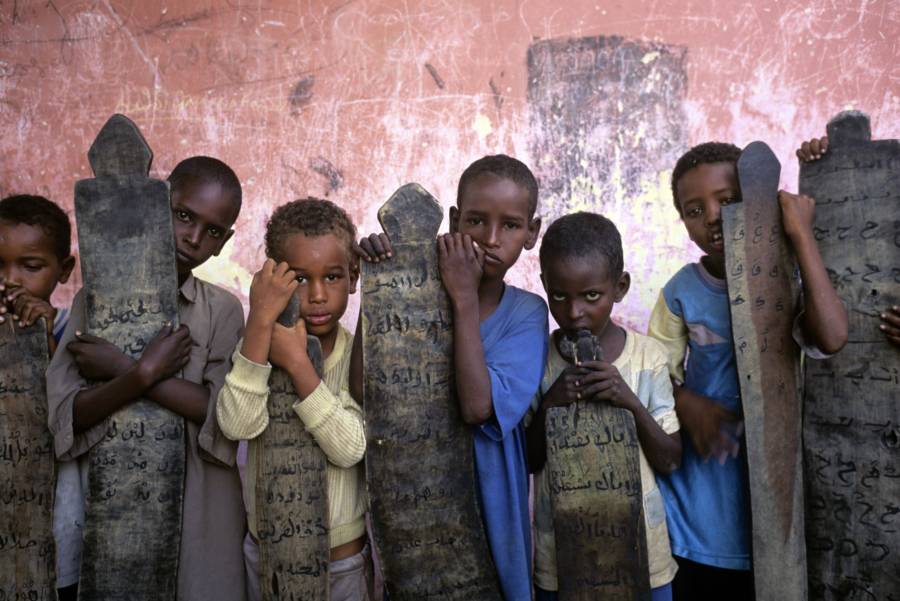

Joe McNally/Getty ImagesYoung Rwandan boys pose with grave stones in their grasp in Dec. 1996.

The government in place after the Rwandan Genocide wasted no time in trying to root out the causes of the killings. Tensions between Hutus and Tutsis still exist, but the government has taken great efforts to officially "erase" ethnicity in Rwanda. Government IDs no longer list the bearer's ethnicity, and speaking "provocatively" about ethnicity can result in a prison sentence.

In a further effort to break all bonds with its colonial past, Rwanda switched the language of its schools from French to English and joined the British Commonwealth in 2009. With the help of foreign aid, Rwanda's economy essentially tripled in size in the decade after the genocide. Today, the country is considered one of the most politically and economically stable in Africa.

So many men had been killed during the genocide that the entire country's population was nearly 70 percent female in the aftermath. This led President Paul Kagame (still in office) to lead a huge effort for the advancement of Rwandan women, with the unexpected yet welcome result that today the Rwandan government is widely hailed as one of the most inclusive of women in the world.

The country that 24 years ago was the site of unthinkable slaughter today has a Level 1 travel advisory rating from the U.S. Department of State: the safest designation that can be bestowed on a country (and higher than that of both Denmark and Germany, for example).

Despite this tremendous progress in only a little more than two decades, the brutal legacy of the genocide will never fully be forgotten (and has since been documened in films like 2004's Hotel Rwanda). Mass graves are still being uncovered to this day, hidden beneath ordinary houses, and memorials such as that at Ntarama Church serve as grim reminders of how quickly and easily violence can be unleashed.

After this look at the Rwandan Genocide, witness the widely-forgotten horrors of the Armenian Genocide. Then, see the killing fields of the Cambodian Genocide.