In the U.S. alone, the vibrator is a billion dollar industry. But how long have they really been around, and who invented them?

An early vibrator ad. Image Source: Wikipedia

A sex toy staple, the rise of the vibrator has always been linked to the hysteria treatments of Victorian England. But the Victorians were hardly the first to employ “pelvic massage” as a medical treatment. As it happens, the history of the vibrator is much longer than that:

The Vibrator’s Ancient Origins

The term hysteria — from the Greek word for uterus, hysteros — originated some 2,500 years ago and described a triad of symptoms experienced by women: fatigue, nervousness and depression. Hippocrates believed that these symptoms were caused by a “wandering uterus,” and given the science of the time, it was as logical an assumption as anything else.

Questionable anatomy aside, dildos apparently appeared as an answer to this set of problems, having been found in places dating back to this period. In Ancient Egypt, legend has it that Cleopatra filled a hollowed out gourd with bees and used it for clitoral stimulation. It’s likely just an urban legend, though: she probably just used dildos, like every other woman of her time.

From Medieval times throughout the Renaissance, village doctors viewed hysteria as a sign of sexual deprivation, and thus encouraged married hysteria sufferers to engage in rigorous sex to cure their ails.

In fact, for much of history, the pursuit of the female orgasm was more important than we’ve been led to believe: even in the Victorian era, sex guides touted the female orgasm as essential to pregnancy. If a man wanted an heir, the female orgasm, and foreplay, were essential.

Vibrators In The Victoria Era

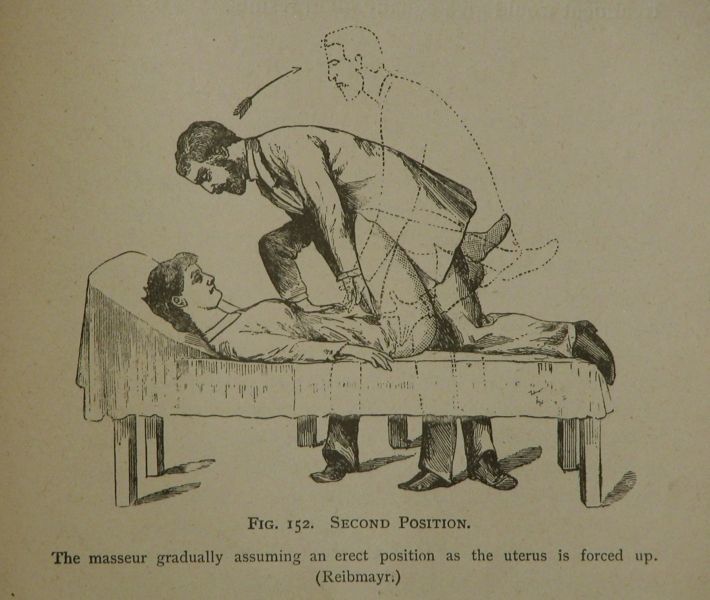

A Victorian era doctor comes to the aid of his patient. Image Source: Wikipedia

The Victorians did coin a term for the orgasm: hysterical paroxysm. The clinical definition added a degree of scientific legitimacy to the experience, but was concurrent with a belief that masturbation was sinful and even harmful (although a few doctors conceded that it might have been okay for women on their periods).

If a “hysterical” woman was unmarried and didn’t have the option or interest in “rigorous sexual intercourse,” she still had to achieve that curative hysterical paroxysm somehow.

At first, midwives and medical doctors — predominantly men at the time — manually massaged a woman’s vulva and clitoral region in order for the woman to experience a “hysterical paroxysm.” The intended effect did wear off, meaning that women would come back for more treatment — and after a while, physicians ran into a significant challenge: their hands and wrists were getting tired and, in some cases, probably bordering on repetitive motion injuries like tendonitis.

The necessity for an automated massager begat the first of many automatic “vibrators”: more specifically, a rather large, steam-powered one that practically took up an entire room and was known as “The Manipulator.”

Perhaps the most well-known iteration, in part because of the major motion picture that dramatized the story, is Dr. Joseph Mortimer Granville’s 1880 invention of the first electric vibrator.

Granville never meant to treat “hysterics” with his device; rather, he meant for it to treat musculoskeletal pain in men. Nevertheless, these devices reduced the time it took for women to achieve her paroxysm — helpful as at the time many doctors feared a “hysteria” epidemic — and soon became smaller and more portable, opening up the door for new innovations by actors outside the medical field.