What the world gets right and wrong about the connections between Islam and slavery.

SAFIN HAMED/AFP/Getty ImagesHaifa, a 36-year-old woman from Iraq’s Yazidi community who was taken as a sex slave by ISIS, stands on a street during an interview with AFP journalists in the northern Iraqi city of Dohuk on November 17, 2016.

“These are evil personalities,” Philippine military spokesman Jo-Ar Herrera said at a news conference in June, referring to the Islamic militants who had then been besieging the city of Marawi for five weeks.

What Herrera was addressing wasn’t the fact that these ISIS-affiliated militants had taken over chunks of Marawi, killing about 100 and displacing nearly 250,000 in the process. Instead, Herrera was referencing the reports that the militants had been taking civilians captive, forcing them to loot homes, convert to Islam, and, worst of all, act as sex slaves.

This was indeed the aspect of the battle for Marawi that made headlines around the world.

And just a week later, separate reports from 5,600 miles away in Raqqa, Syria detailed the horrific extent of ISIS’ practice of taking slaves, largely for sexual servitude. Women who had lived as wives to ISIS fighters spoke with an Arabic television reporter and revealed that their husbands had ripped girls as young as nine from their parents so that they could rape them and keep them as sex slaves.

With details like this making headlines again and again throughout ISIS’ three-year reign, it’s left many in the West asking just what, if any, is the connection between not only ISIS, but perhaps even Islam itself, and the taking of slaves?

Slavery In Historical Islam

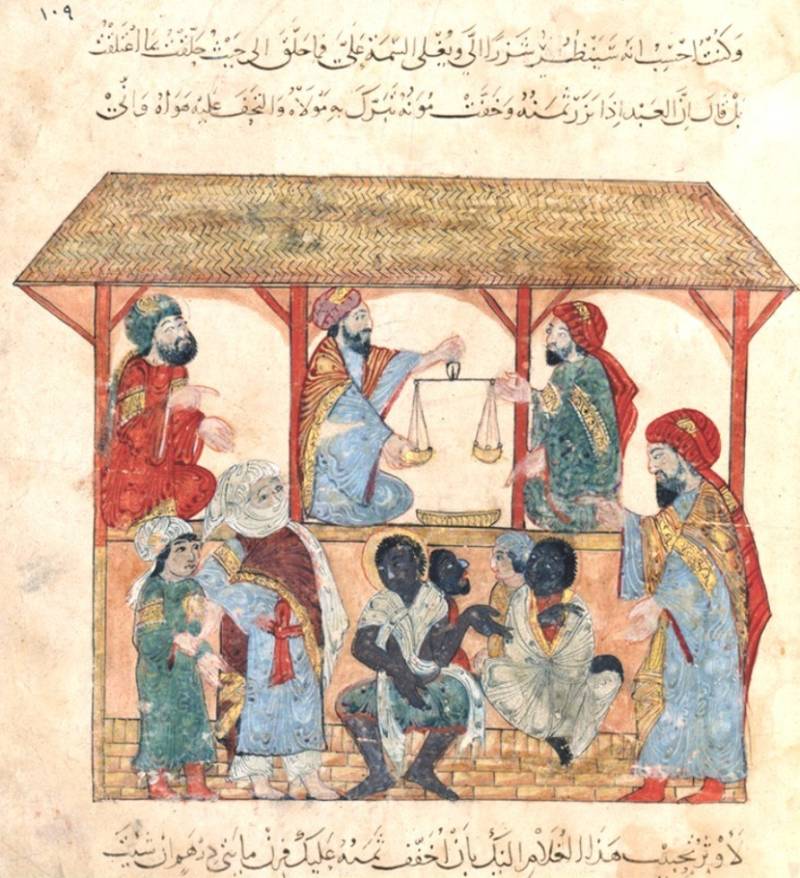

Wikimedia CommonsA 13th-century slave market in Yemen.

Slavery had existed in pre-Islamic Arabia, of course. Before the rise of the Prophet Muhammad in the seventh century, the region’s various tribes engaged in frequent small-scale wars, and it was common for them to take captives as spoils.

Islam then codified and greatly expanded this practice, if for no other reason than the fact that a unified Islamic state was capable of much larger-scale warfare than ever before, and that its slave economy benefited from economies of scale.

As the first caliphate swept across Mesopotamia, Persia, and North Africa in the seventh century, hundreds of thousands of captives, largely children and young women, flooded into the Islamic empire’s core territory. There, these captives were put to work in almost any job there was to do.

Male African slaves were favored for heavy-duty work in salt mines and on sugar plantations. Older men and women cleaned streets and scrubbed floors in wealthy households. Boys and girls alike were kept as sexual property.

Male slaves who were taken as toddlers or very young children could be inducted into the military, where they formed the core of the feared Janissary Corps, a kind of Muslim shock troop division that was kept tightly disciplined and used to break enemy resistance. Tens of thousands of male slaves were also castrated, in a procedure that usually involved the removal of both the testicles and the penis, and forced to work in mosques and as harem guards.

Slaves were one of the principal spoils of empire, and the newly enriched Muslim master class did with them what they liked. Beatings and rapes came frequently for many, if not most, domestic servants. Harsh lashings, for example, were used as motivation for Africans in the mines and on trading ships.

Arguably the worst treatment was meted out to East African slaves (known as Zanj) in Iraq’s marshy south.

This area was prone to flooding and by the Islamic era, it had largely been abandoned by its native farmers. Wealthy Muslim landlords were given titles to this land by the Abbasid Caliphate (which came to power in 750), on the condition that they bring in a profitable sugar crop.

The new landowners approached this task by throwing tens of thousands of black slaves into the swamps and beating them until the land was drained and a paltry harvest could be raised. Because swamp farming is not terribly productive, the slaves often worked without food for days at a time, and any disruption – which threatened the already-slim profits – was punished with mutilation or death.

This treatment helped spark the Zanj Rebellion in 869, which lasted 14 years and saw the revolting slave army get within two days’ march of Baghdad. Somewhere between a few hundred thousand and 2.5 million people died in this fight, and when it was over, the thought leaders of the Islamic world gave some thought to how to prevent such unpleasantness in the future.

The Philosophy Of Islamic Slavery

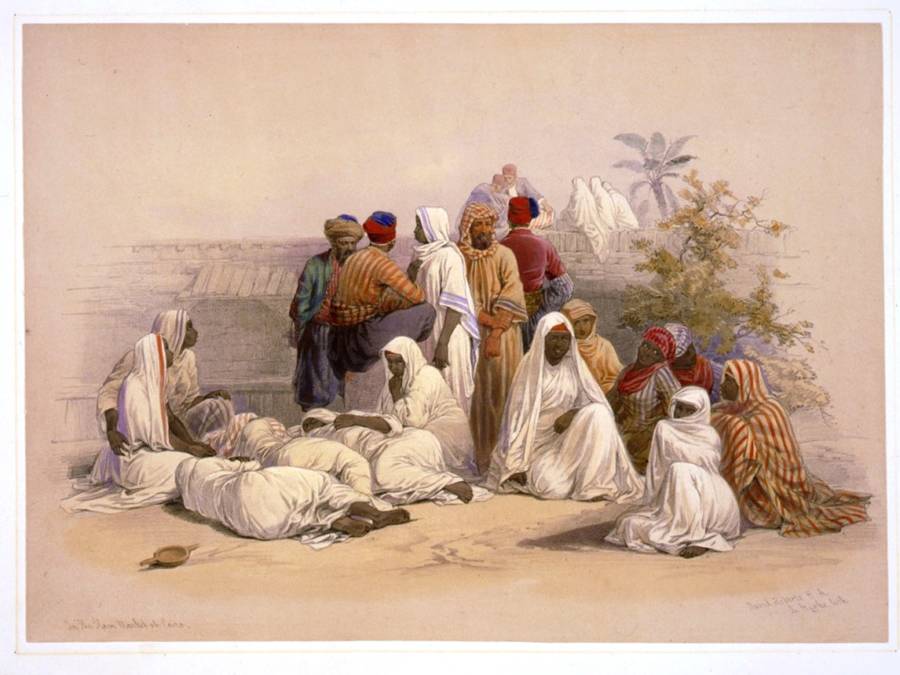

David Roberts/Louis Haghe/Library of CongressSlave market in Cairo. Published circa 1846-1849.

Some of the reforms that grew out of the Zanj Rebellion were practical. Laws were passed to limit the concentration of slaves in any one area, for example, and breeding of slaves was strictly controlled with castration and by banning casual sex among them.

Other changes, however, were theological, as the institution of slavery came under religious guidance and rules that had been present since the time of Muhammad, such as the ban on keeping Muslim slaves. These reforms completed the conversion of slavery from a non-Islamic practice into a bona fide facet of Islam.

Slavery is mentioned nearly 30 times in the Quran, mostly in an ethical context, but some explicit rules for the practice are set out in the holy book.

Free Muslims must not be enslaved, for example, though captives and the children of slaves may become “those whom your right hand has possessed.” Foreigners and strangers were presumed to be free until shown to be otherwise, and Islam forbids racial discrimination in the matter of slavery, though in practice, black Africans and captured Indians have always made up the bulk of the slave populations in the Muslim world.

Slaves and their masters are definitively unequal – socially, slaves occupy a status similar to children, widows, and the infirm – but they are spiritual equals, technically under the stewardship of their masters, and will face Allah’s judgment in the same way when they die.

Contrary to some interpretations, slaves do not have to be freed when they adopt Islam, though masters are encouraged to educate their slaves in the religion. Freeing slaves was permissible in Islam, and many wealthy men either freed some of their own slaves or bought freedom for others’ as an act of atonement for sin. Islam requires the regular paying of alms, and this could be done by manumitting a slave.

The Other African Slave Trade

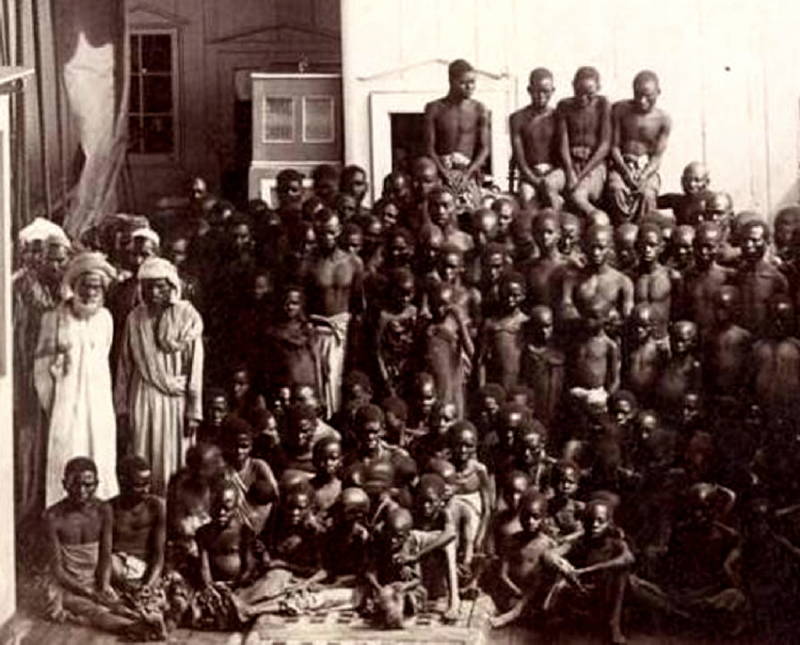

WikimediaRescued African slaves and their Arab captors in Zanzibar. 1881.

From the beginning of the Islamic era, slavers had been staging raids against the coastal tribes of equatorial East Africa. When the Sultanate of Zanzibar was established in the ninth century, the raids shifted inland to present-day Kenya and Uganda. Slaves were taken from as far south as Mozambique and as far north as Sudan.

Many slaves went to the mines and plantations of the Middle East, but many more went to Muslim territories in India and Java. These slaves were used as a kind of international currency, with up to hundreds of them being given as gifts to Chinese diplomatic parties. As Muslim power expanded, Arab slavers spread to North Africa and found a very lucrative trade waiting for them in the Mediterranean.

Islamic rules mandating gentle treatment of slaves didn’t apply to any of the Africans being bought and sold in the Mediterranean trade. Visiting a slave market in 1609, Portuguese missionary João dos Santos wrote that Arab slavers had a “custome to sew up their females, especially their slaves being young to make them unable for conception, which makes these slaves sell dearer, both for their chastitie, and for better confidence which their masters put in them.”

Despite such accounts, when Westerners think of African slavery, what comes to mind more than anything is the transatlantic trade of some 12 million African slaves, which stretched from roughly 1500 to 1800, when the British and American navies began interdiction against slave ships. The Islamic slave trade, however, began with the Berber conquest in the early eighth century and remains active to this day.

During the years of the American slave trade, some historians suggest that at least 1 million Europeans and 2.5 million total were taken as slaves by majority-Muslim forces throughout the Arab region. In total, wildly varying estimates also suggest that between the start of the Islamic era in the ninth century and the supremacy of European colonialism in the 19th, the Arab trade could have taken well over 10 million slaves.

Long caravans of slaves – black, brown, and white – were driven across the Sahara for more than 1,200 years. These trips through the desert could take months, and the toll on the slaves was enormous, and not just in terms of lives lost.

As reported in 1814 by Swiss explorer Johann Burckhardt: “I frequently witnessed scenes of the most shameless indecency, which the traders, who were the principal actors, only laughed at. I may venture to state that very few female slaves who have passed their tenth year, reach Egypt or Arabia in a state of virginity.”