After four white police officers were acquitted for the beating of Rodney King in April 1992, protests turned violent as the LA riots left 53 dead, 2,000 injured, and thousands incarcerated.

On April 29, 1992, the streets of South Central Los Angeles erupted into chaos. Four white officers of the LAPD had just been acquitted by a nearly all-white jury in the violent, videotaped beating of a black man named Rodney King — and the city’s black community was now incensed.

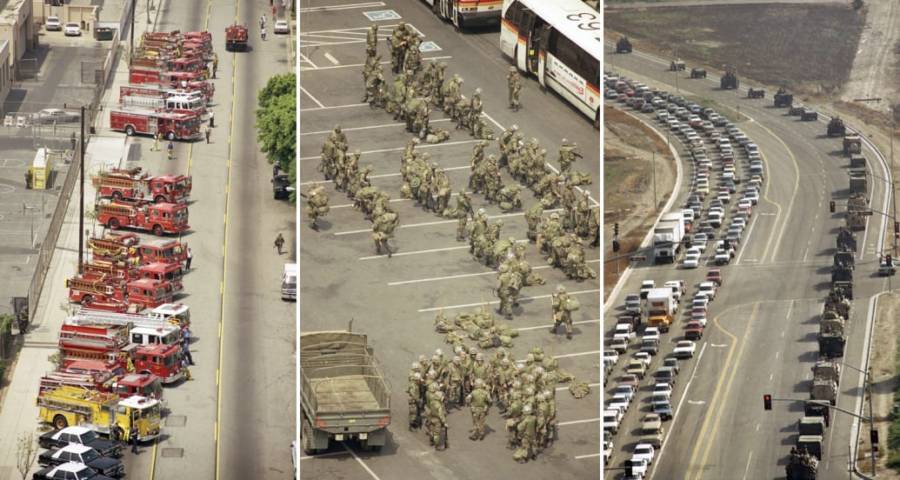

For five days, the public protested in what has since become known as the LA riots or the Rodney King riots, which ultimately reduced entire swathes of the city to rubble. By the time the National Guard came in six days later, 55 people were dead, more than 2,000 were injured, and more than $1 billion worth of property damage was left to clean up.

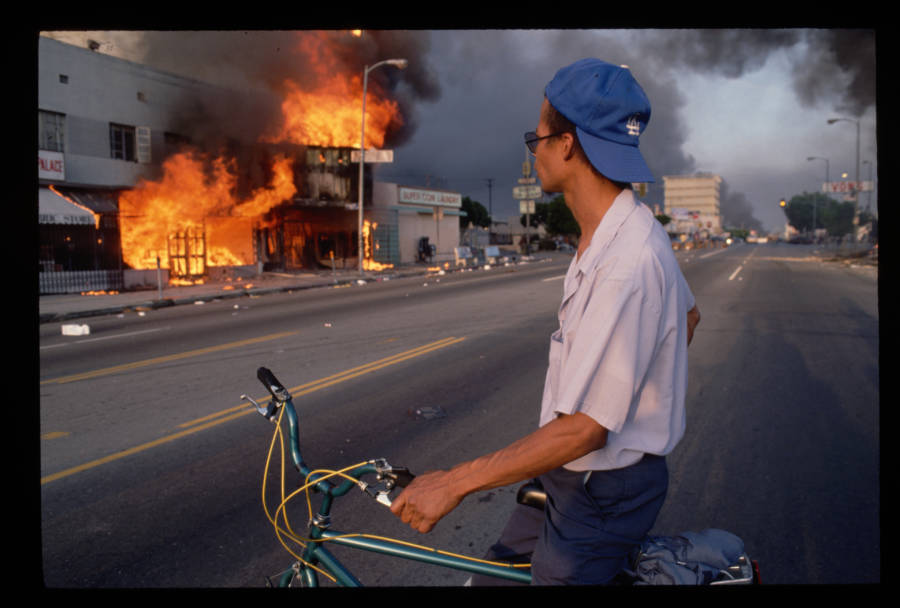

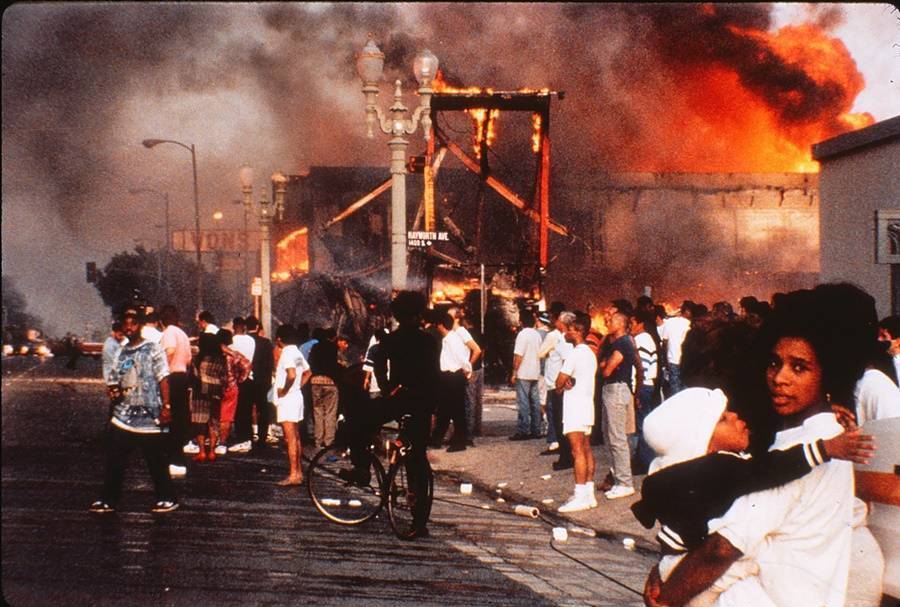

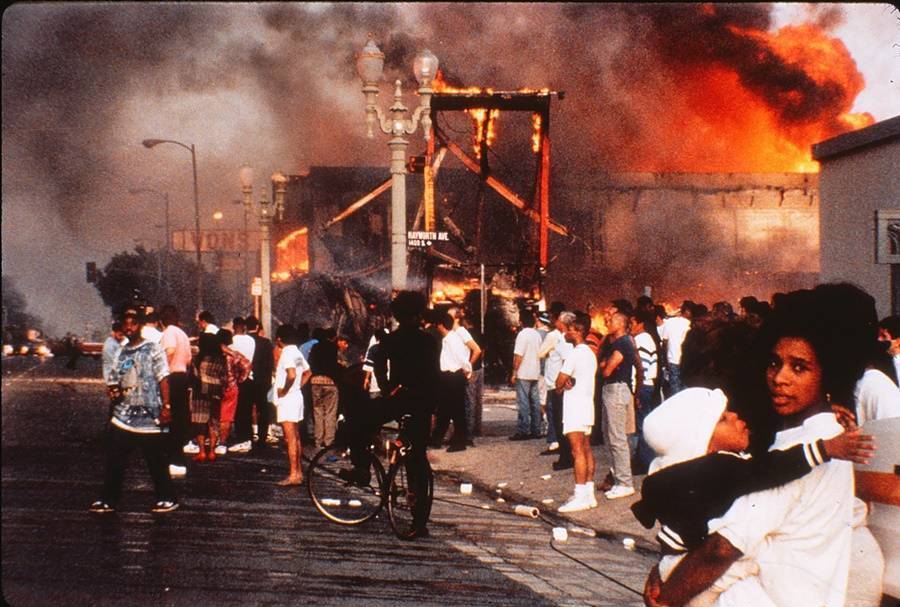

Peter Turnley/Corbis/VCG via Getty ImagesA young man on a bicycle watches buildings burn during the 1992 LA riots sparked by the acquittal of several LAPD officers caught on video beating a black man Rodney King.

But the 1992 Los Angeles riots represented more than a response to just one severely mishandled case of police brutality. They were instead but one symptom of a larger disease of unchecked police brutality and corruption, racism, and inequality that was rampant across Los Angeles at the time and had been for decades.

“Black people are disenfranchised in this community,” business owner Moddie V. Wilson III told a reporter a day after the riots. “We don’t have many stores, but some had started to come back. Now I don’t know.”

“It’s gotten beyond Rodney King,” Wilson added, clearly alluding to the factors that caused the LA riots and foreshadowing their long legacy. “Rodney King was just the straw that broke the camel’s back.”

A Crime Epidemic And Citywide Racism Fuel The LA Riots

To this day, the nearly 10 years between the late ’80s and mid-’90s in Los Angeles are widely known as the “decade of death.”

At the time, low-income communities of color in and around South Central LA were both in the midst of a crack epidemic and overrun by gangs like the Crips and Bloods. Drive-by shootings had become a daily occurrence as some 1,000 people were killed annually during the worst years, typically in connection with gang violence.

Those gangs, according to a report from the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office, boasted some 150,000 members by 1992, the year of the riots. With 936 active gangs, nearly half of the county’s young, black males were involved with gang activity.

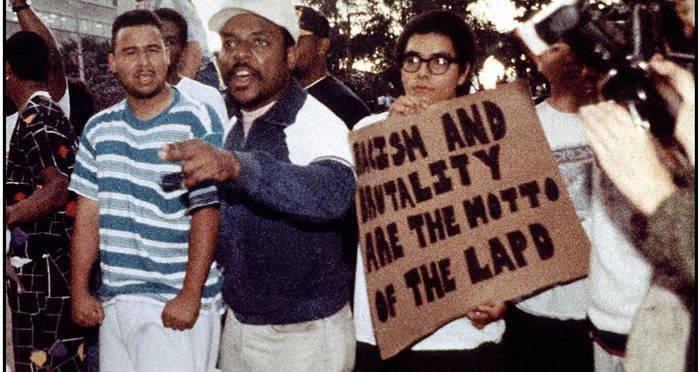

Mike Nelson/AFP/Getty ImagesA demonstrator protests the verdict in the Rodney King beating outside the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) headquarters.

But it wasn’t just black gangs, and racial tensions added another layer to the existing crime issues. South Central LA had been predominately populated by African-Americans between the 1970s and 1980s, but a wave of immigrants from Latin America and Asia had begun to change the neighborhood’s racial makeup as the riots approached. Eventually, South Central’s mostly black population was half of what it had been a generation earlier by the time the 1990s rolled around.

At the same time, many poor and minority neighborhoods had fallen into disrepair due to neglect and divestment. In South Central, nearly half of the black male population was unemployed.

With changing demographics and urban neglect as well as unemployment causing strife, tensions bubbled between various combinations of ethnic groups in South Central, including blacks and Koreans. For example, around the same time that Rodney King was beaten by local police, 15-year-old African-American teen Latasha Harlins was shot and killed by a Korean-American store owner, Soon Ja Du, after a brief altercation in which Du suspected Harlins of stealing.

Du, who was convicted of voluntary manslaughter but never received prison time, claimed the killing was in self-defense — though Harlins had been unarmed. Harlin’s murder and Du’s sentencing only increased tension between South Central’s black and Korean communities, tension that would rear its ugly head again during the riots.

But more than anything, the greatest tension that set the stage for the LA riots was surely that between the city’s black community and its police force.

Police Corruption And Brutality

Communities of color in America have always historically been over-policed, and LA in the era of the riots (and for years upon years beforehand) was a glaring example of this.

Going all the way back to the ’60s, when LA was seeing a dramatic rise in its black population, tensions between this community and the LAPD had sometimes turned violent.

The most intense example of this was undoubtedly the Watts riot of 1965, which started when police pulled over a young black man for reckless driving and a scuffle ensued between the officers, the young man, and his family. Accounts of the scuffle vary, but when word got out that police had brutalized the man and his mother, an angry populace already frustrated with mistreatment by the authorities lashed out. With eerie foreshadowing of what was to come, the rioting lasted six days and only ended when the California Army National Guard came in, at which point 34 were dead and some 3,500 had been arrested.

With racially-motivated tensions between police and LA blacks long since established, relations between the LAPD (which was about 60 percent white) and the city’s citizens only grew worse as the department grew more aggressive and even corrupt.

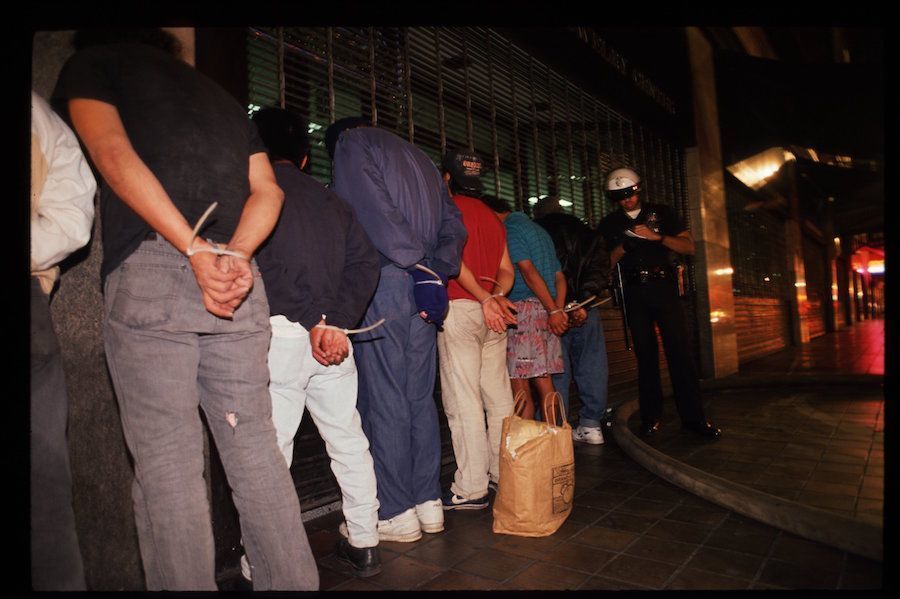

This abuse of authority was, in the years leading up to the Rodney King riots, typified by Operation Hammer, an LAPD initiative beginning in 1987 that saw officers under Chief Daryl Gates conduct massive sweeps and roundups of suspected gang members — in ways that went well beyond protect and serve.

These sweeps routinely saw huge numbers of officers conduct raids on suspected gang-infested areas and brutalize suspects of even just passersby with impunity. Rarely did these sweeps lead to arrests, let alone prosecutions and convictions, but instead they were meant to “send a message.”

That’s precisely what Officer Todd Patrick said about one particularly intense Operation Hammer raid that took place in August 1988 and saw police round up, humiliate, and beat dozens of people in two adjacent apartment buildings under the guise of looking for drug dealers. The raid netted just a tiny amount of drugs — but that’s because it wasn’t really about confiscating contraband in the first place.

“We weren’t just searching for drugs,” Patrick later said. “We were delivering a message that there was a price to pay for selling drugs and being a gang member… I looked at it as something of a Normandy Beach, a D-day.”

Eventually, in the wake of the Rodney King riots, a number of the officers involved were prosecuted — just some of the 1,400 officers who were investigated for excessive force in the late ’80s, with only one percent prosecuted.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=18A-FAipK8k

Likewise, a New York Times report from 1991 stated that from 1986 to 1991, more than 2,000 lawsuits were filed against the LAPD for excessive force. Of those 2,000, only 42 gained any legal traction.

“It was an open campaign to suppress and contain the black community,” lawyer and civil rights activist Connie Rice told NPR.

“LAPD didn’t even feel it was necessary to distinguish between pruning out a suspected criminal where they had probable cause to stop and just stopping African-American judges and senators and prominent athletes and celebrities simply because they were driving nice cars.”

The Rodney King Beating

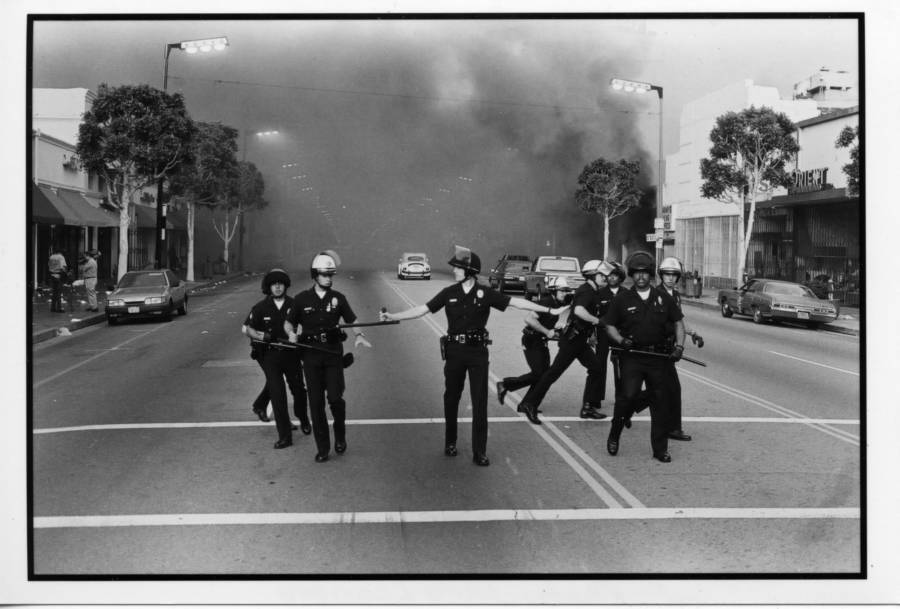

Ted Soqui/Corbis/Getty ImagesThe Rodney King riots showed the country how desperate the situation in Los Angeles had become for its minorities.

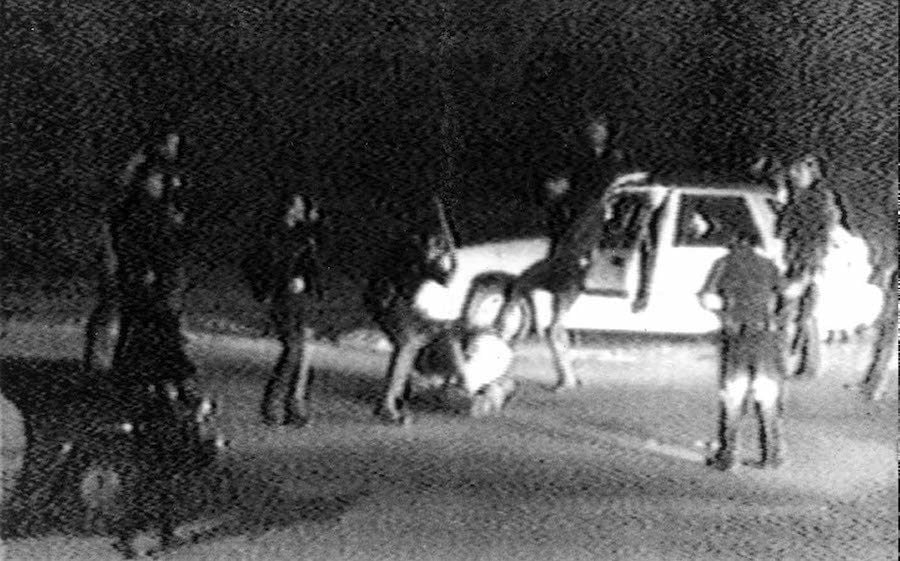

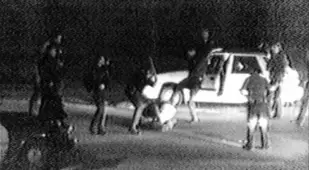

On March 3, 1991, police officers tried to pull over a young black man named Rodney King for a traffic violation. King, who had been drinking and was on probation, instead led police on a high-speed chase. King eventually pulled off the freeway and stopped his car in front of an apartment building in the San Fernando Valley.

Police ordered King out of the car. Then, the officers descended on him violently. King was kicked and beaten with batons for 15 minutes.

George Holliday, a resident of the apartment building, videotaped the incident. It was later broadcast on local station KTLA and news networks nationwide. The video showed a defenseless King on the ground as he was bludgeoned by a group of LAPD officers while more than a dozen other cops stood by and watched.

King had been struck at least 55 times during the attack and as a result suffered from skull fractures, broken bones and teeth, and brain damage.

Mass outrage followed the video of King’s attack and arrest. Within a week, a Los Angeles County grand jury released an indictment charging the four officers in the video — Sgt. Stacey Koon, Officers Theodore Briseno, Laurence Powell, and Timothy Wind — with felony assault and other offenses. All four cops pleaded not guilty.

A year later, on April 29, 1992, a trial jury consisting of 12 mostly white suburban LA residents and no African-American citizens found the four officers not guilty.

Destruction And Devastation Across Los Angeles After The Acquittal

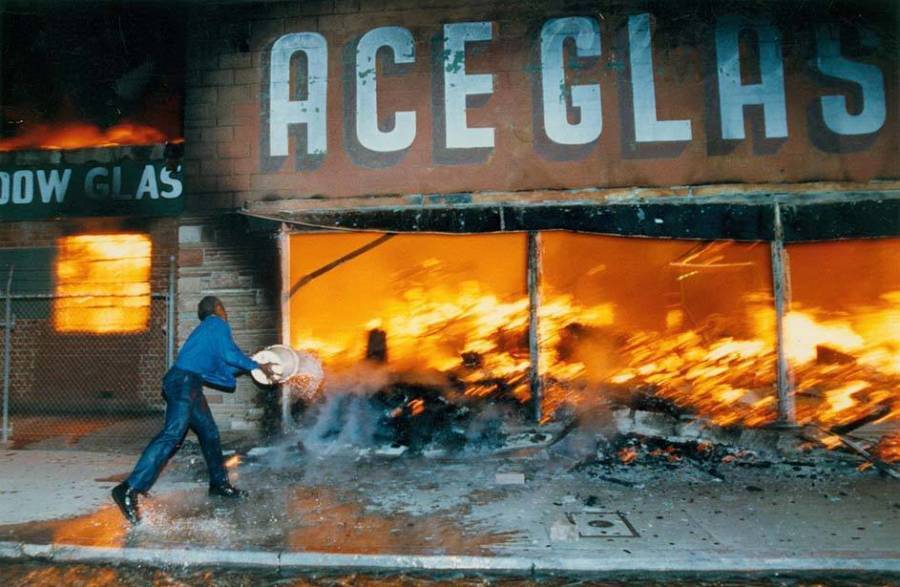

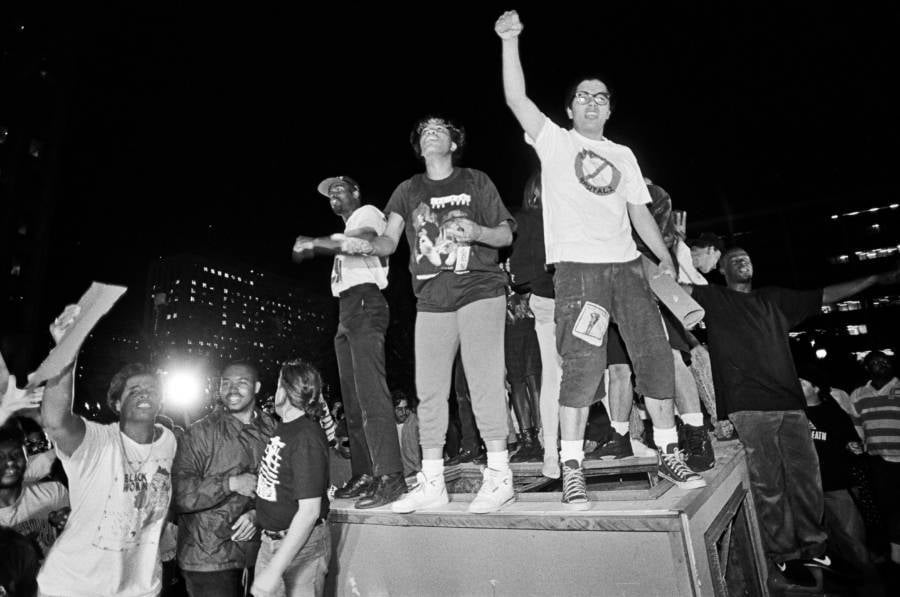

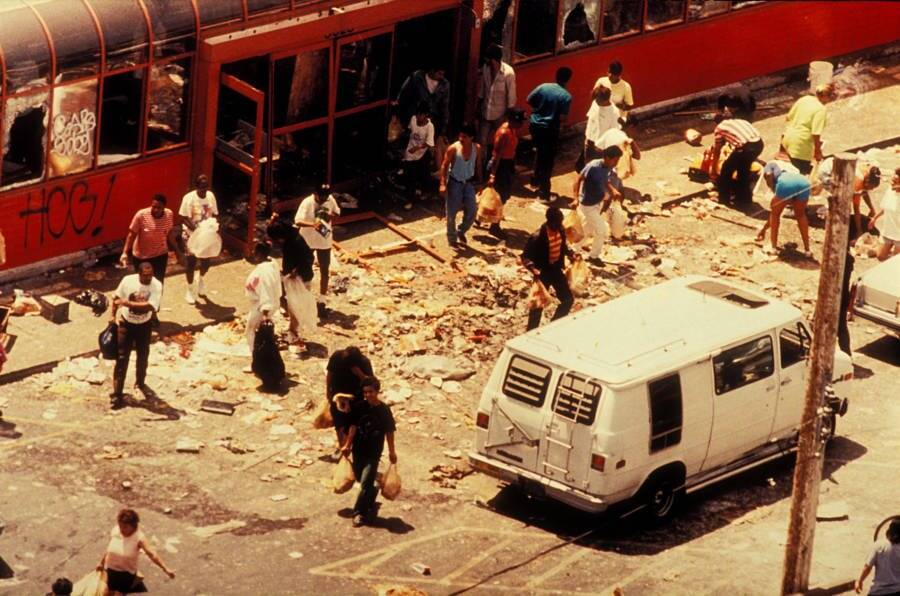

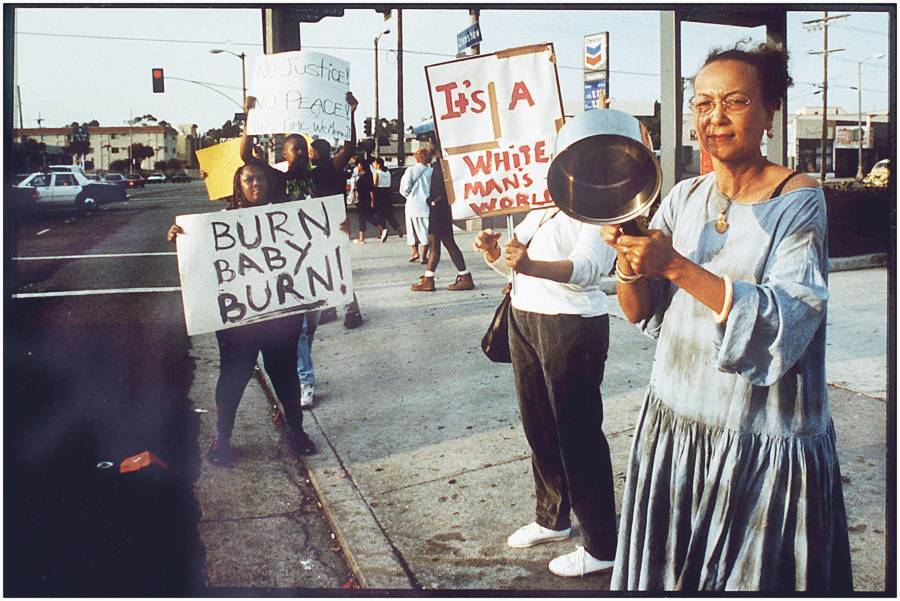

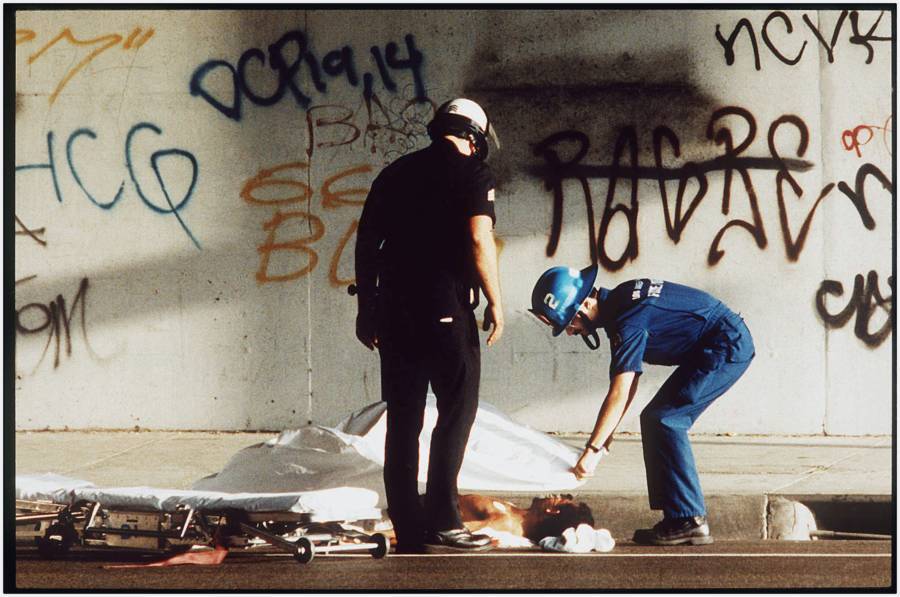

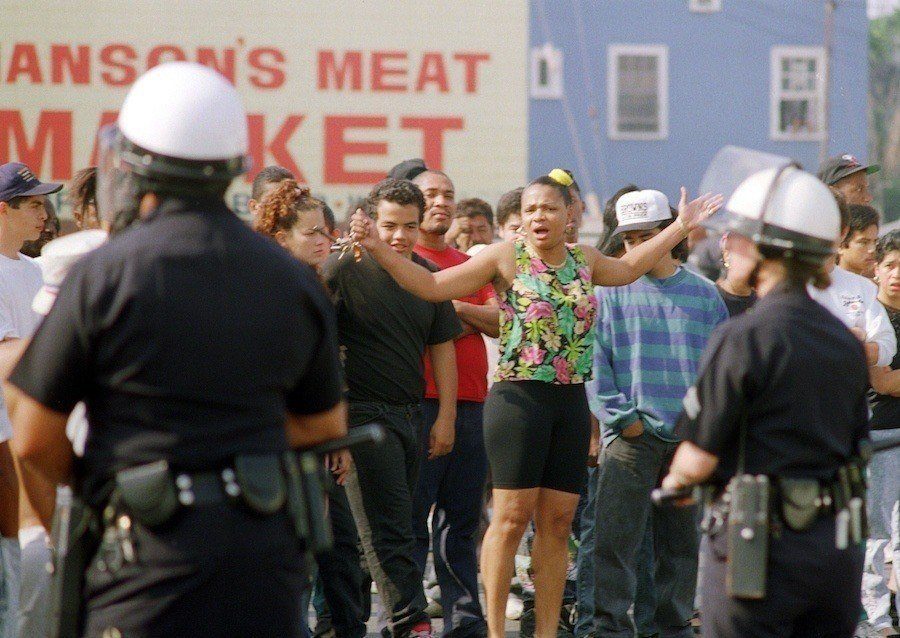

Within the hours of the acquittal, angry residents took to the streets. Hundreds gathered in protest outside the LAPD headquarters. They destroyed, looted, and burned down buildings.

Almost as soon as the LA riots began, people started calling 911. But the city did not respond to these calls until well after the first calls were made. This only felt like more evidence to the residents of South Central LA that their city had failed them and that the police didn't care about them one bit.

Resident Terri Barnett, for one, remembered her experience with her boyfriend and two other African-American residents in the LA riots. "There were four cops in each car that passed by," Barnett told NPR. "They saw us. They looked right through us."

Her group would, later that day on April 29, come to the aid of a white trucker named Reginald Denny who had been viciously attacked by several people soon after the riots began.

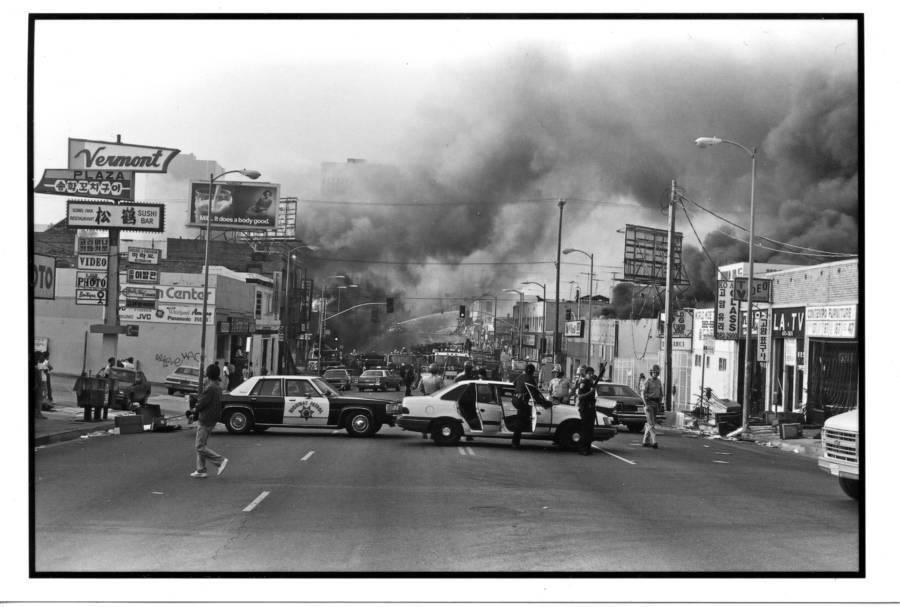

Kirk McKoy/Los Angeles Times/Getty ImagesThe 1992 LA riots lasted a grueling five days during which incensed citizens looted and burned shops across the city.

But Barnett wasn't alone in feeling like what had begun was about a lot more than one miscarriage of justice. Instead, it was about a widespread and longstanding pattern of oppression and abuse.

"This is no longer about Rodney King," said an Asian-American man captured on footage in the Smithsonian documentary The Lost Tapes: L.A. Riots. "This is about the system against us, the minorities."

Without an immediate response from the LAPD, residents were left to endure the uncontrollable disarray of their neighborhoods alone. A Los Angeles Times reporter wrote of one such bizarre scene amid the violence:

"At the corner of 43rd Place and Crenshaw, more than a dozen laughing and animated patrons packed the tiny Crenshaw Cafe's outdoor tables, sipping coffee and dining on a hearty breakfast of pancakes and eggs. Across the street a ferocious fire was blazing, sending a trail of destruction through a manicure shop and the Muslim Community Center."

Later reports showed that law enforcement did not respond to distress calls during the 1992 LA riots until three hours after the violence had broken out. And, despite LAPD Chief Darryl Gates' announcement that his officers had the situation under control, the city did not have any official plans.

According to journalist Joe Domanick, who studied and wrote about the 1992 Rodney King riots, Chief Gates in fact went to speak at a fundraiser in West LA when the riots broke out and reportedly ordered cops to retreat. The situation had grown so catastrophic that the police themselves were now fleeing the scene.

Police Flee And Citizens Fight Back

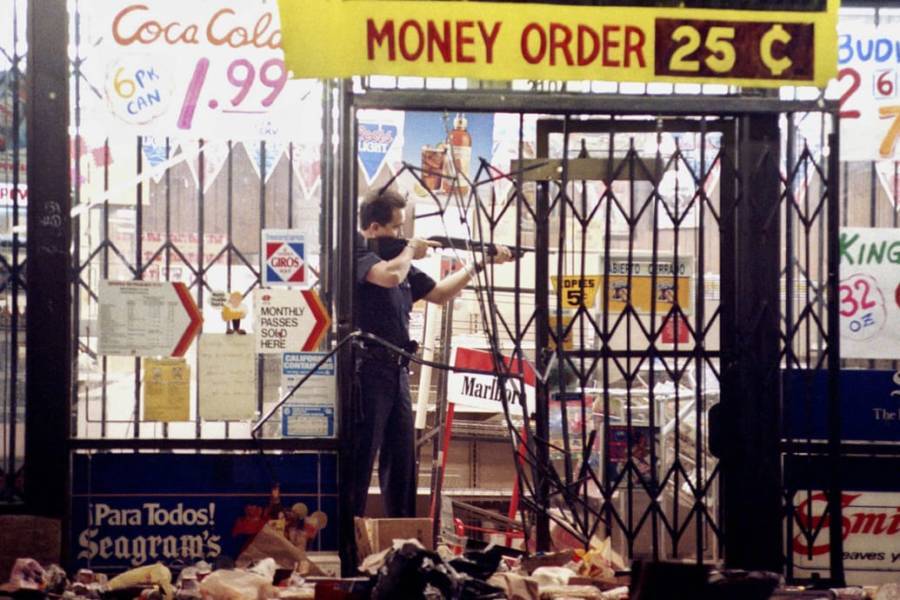

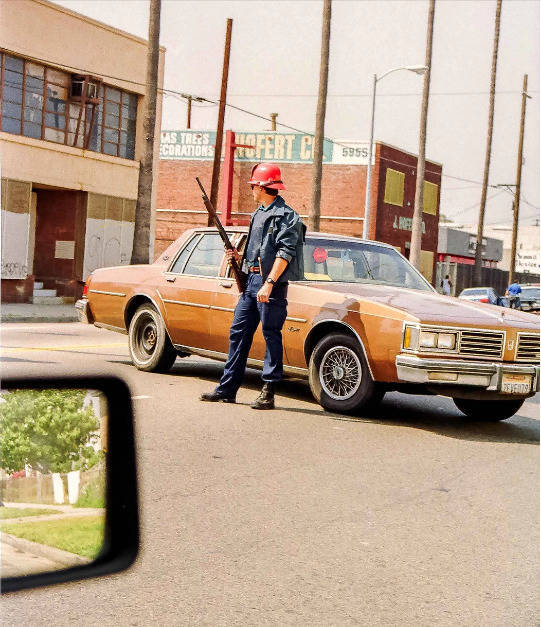

Though in retreat, police created a barrier between Koreatown and richer neighborhoods like Beverly Hills.

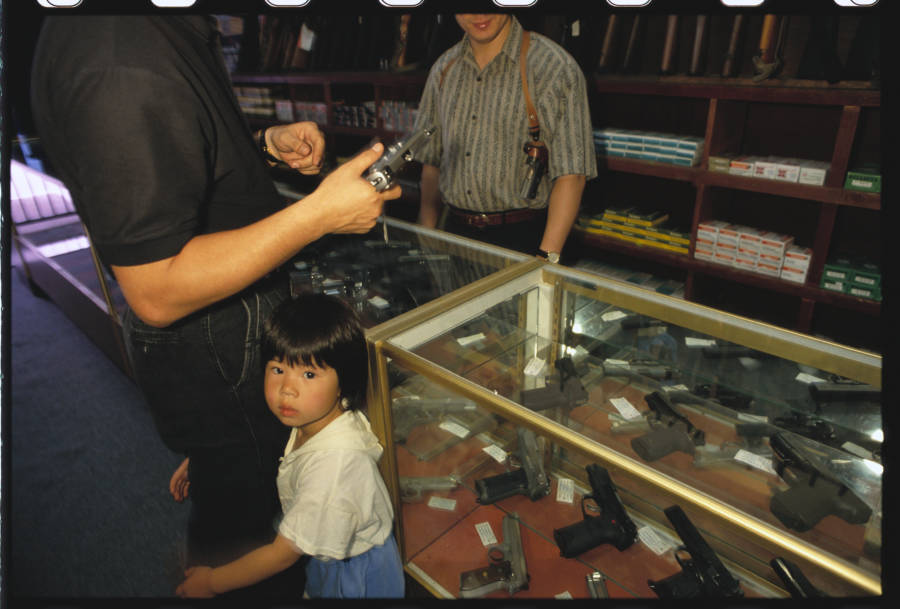

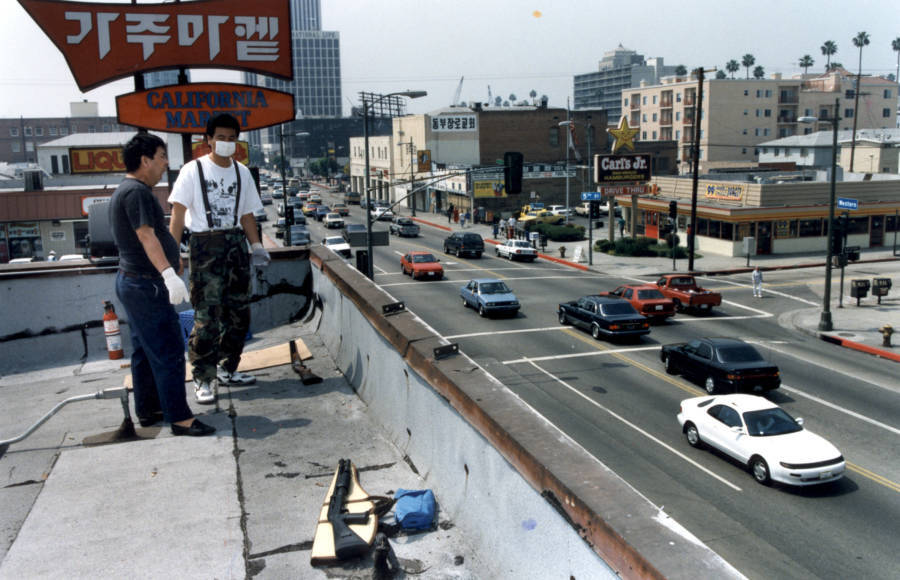

As such, residents were trapped in the chaos taking place across Koreatown and elsewhere. Korean residents were thus left particularly vulnerable — and some of them fought back.

While residents of Koreatown certainly weren't the only ones to fight back, their stories have become the most emblematic of this dire phase of the LA riots in which people had to fend for themselves in what was essentially a cop-less war zone.

Shopkeepers like 35-year-old Chang Lee took up arms and bunkered themselves inside their stores or on the roof, ready to scream — or even fire — at any looters who got too close. Lee remembers sitting on his rooftop, clutching a gun and whispering to himself "where are the police?" over and over.

And while Lee was pinned on that rooftop protecting his grocery store, he used his portable TV to see news footage of a nearby gas station that was burning to the ground at that moment — then he realized that it was his gas station. A young entrepreneur, Lee owned several businesses in Koreatown, but now they were falling before his eyes.

At the same time, business owner Kee Whan Ha was preparing to defend his interests after realizing that the cops were nowhere to be found.

"From Wednesday, I don't see any police patrol car whatsoever," he said. "That's a wide-open area, so it is like Wild West in old days, like there's nothing there. We are the only one left, so we have to do our own."

Getty ImagesApproximately 2,000 Korean-run businesses were damaged or destroyed in the riots.

And what made stories of those like Lee sting all the more is that they believe, with good reason, that the police let the terror in Koreatown happen.

"I truly thought I was a part of mainstream society," Lee said. "Nothing in my life indicated I was a secondary citizen until the LA riots. The LAPD powers that be decided to protect the 'haves' and the Korean community did not have any political voice or power. They left us to burn."

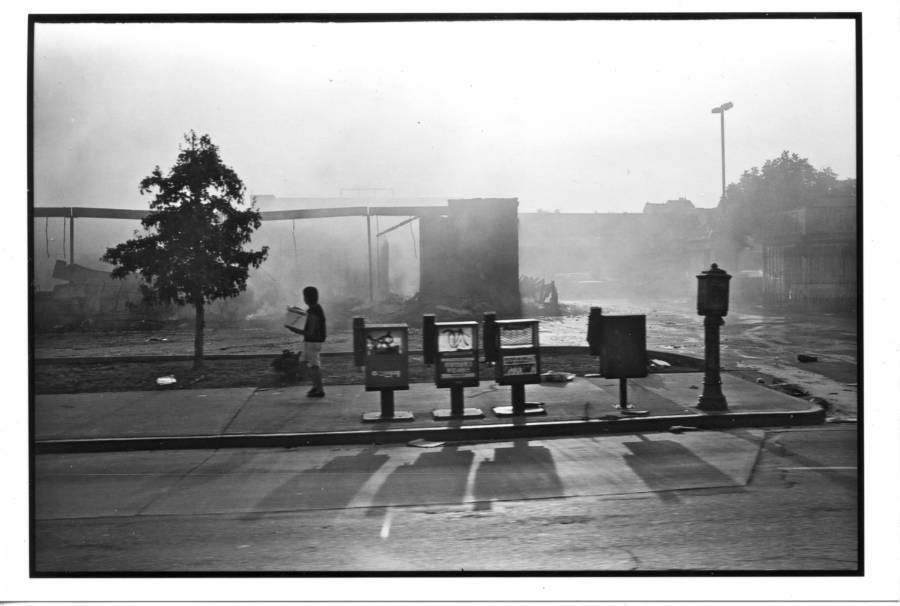

The End And Aftermath Of The 1992 Los Angeles Riots

On the third day of the uprising on May 1, King, who had become an involuntary symbol of the racially-charged riots, spoke publicly against the fighting and looting. He uttered what would become a lasting call for peace, "People, I just want to say, you know, can we all get along? Can we get along?"

That night, Mayor Tom Bradley, the first African-American mayor of Los Angeles, called for a state of emergency while California Governor Pete Wilson requested 2,000 troops from the National Guard. Between a natural denouement and the influx of new law enforcement, the rioting wound down to an end by May 4.

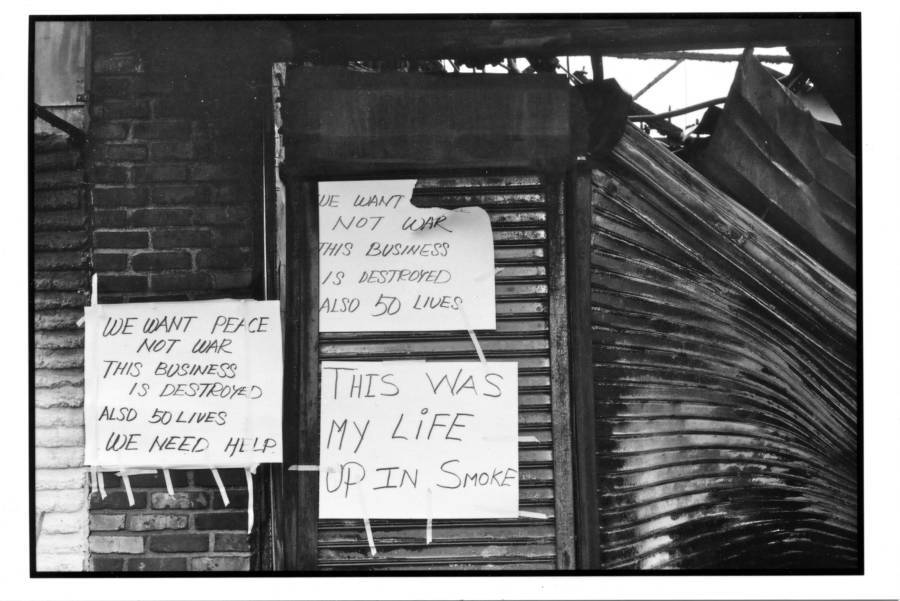

Even with the deployment of the National Guard to support local law enforcement, the devastation left by the 1992 LA riots was unprecedented. More than a thousand buildings were destroyed and approximately 2,000 Korean-run businesses were damaged.

In all, an estimated $1 billion worth of property damage was left in the aftermath. More than 2,000 people were injured and at least 10 people were shot and killed by LAPD officers and National Guardsmen. In total, 55 lay dead.

Nearly 6,000 alleged looters and arsonists were arrested. Despite media coverage that focused disproportionately on black rioters, only 36 percent of rioters who were arrested were African-Americans, while 51 percent were Latinos, according to the Rand Corp.

During the riots, a city curfew from sunset to sunrise had been imposed. Public services such as mail delivery were also stopped, and most LA residents were unable to go to work or school. This only served to further highlight just how much LA's minority populations had been left behind by their city.

The anger and frustration felt by these communities were further compounded by the helplessness they felt as the city's law enforcement, who were meant to serve and protect them, had largely abandoned them. The riots had only confirmed the patterns of abuse that had long been in place.

The Lasting Effects Of The Rodney King Riots

Lindsay Brice/Getty ImagesCrowds gather as businesses burn. An estimated $1 billion was lost due to the riots.

After the fires were extinguished, a federal investigation into the acquittal of the four cops commenced.

In the end, a grand jury returned a two-count indictment against the four officers for use of excessive force and assault with a deadly weapon. Local leaders and activists applauded the new charges.

"I think that this action is going to help bring about a sense of confidence on the part of the people that this system is now working," Mayor Tom Bradley said. "They want to see it pursued to the end."

Two years after the riots, Congress passed Section 14141 of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. This legislation granted authorization to the U.S. Justice Department to investigate local police departments when they exhibit evidence of excessive misconduct and deadly force.

Despite the verdict, the police officers involved in King's case maintained their innocence.

"What can I say? I'm not real happy about it, but I know I didn't do anything wrong so I can't believe they're doing this again to me," said Officer Laurence Powell. "But I still stand by the fact that I didn't do anything wrong. I just did what I was supposed to do."

After the mishandling of the LAPD's response in the Rodney King riots, Chief Gates retired. He called the federal verdict, "dumb, dumb, dumb."

The loss and pain that followed the 1992 LA riots continue to haunt residents decades later. The communities in the neighborhoods in question have largely remained economically displaced, though they have made some progress in recovery since 1992. Meanwhile, South Central LA has been renamed South LA.

Recent reports have also found that the LAPD's police-related killings have somewhat declined, though the department still holds the record for the highest civilian killings in the country. Black residents continue to make up a high percentage of these killings.

Kevork Djansezian/Getty ImagesNot long after he released his memoir, Rodney King was found dead in his home's swimming pool. He was 47.

Rodney King himself published a memoir detailing his struggles in the aftermath of his case and stated in multiple interviews that he had not been able to find steady work afterward. He also struggled with the unwanted fame of the Rodney King riots and his own sobriety.

"As far as having peace within myself, the one way I can do that is forgiving the people who have done wrong to me. It causes more stress to build up anger. Peace is more productive," King said in an interview with The New York Times, one of the last that he would do before his death.

In 2012, King was found dead in a swimming pool at the home he shared with his fiancée. Authorities ruled his death as an "accidental drowning" with the alcohol, cocaine, marijuana, and PCP that was found in his system were deemed to be contributing factors. King was just 47.

"Rodney King was a symbol of civil rights and he represented the anti-police brutality and anti-racial profiling movement of our time," the Rev. Al Sharpton said in a statement. "It was his beating that made America focus on the presence of profiling and police misconduct."

After this intense look at the Rodney King riots, relive the civil rights movement through 55 powerful photos. Then, learn the explosive story of the 1967 Detroit riots.