Source: Flickr Commons

Around 353,000 babies are born every day. Some of them will be born in hospitals, others at home with the assistance of a midwife or doula, while others will make their grand entrance in the back of a car or ambulance somewhere in between home and hospital.

The history of childbirth, and in particular of midwifery, is a complicated and often cyclical one. Throughout 19th century America, midwives attended the majority of births, especially in the American South. Improved medicine and accompanying technologies meant that by the early 20th century, midwifery was highly discouraged, only to come around again when the natural birth movement was born in the 1960s.

In other words, the natural act of childbirth reflected the technological, social and medical beliefs and practices of the time. You can learn a lot about what life was like in a particular time period by examining societal attitudes toward childbirth.

16th Century

Midwives have been around since the beginning of human history. No doubt our caveman ancestors had other female tribe members help hold them up or stagger into a cave long enough to give birth. Even prior to modern language, some human acts require no verbal communication: coitus and childbirth among them.

If we start by looking at a period in history when midwifery became a specified community role, we’d start around 1522. At this point, elder females in communities worldwide ruled the roost when it came to helping younger women deliver babies. Having been licensed and educated in childbirth, midwives were highly respected community members. So much so that when they arrived to aid a laboring woman, it was the mom-to-be’s task to make the midwife feel at home and appreciated, offering her “groaning beer” or special cakes.

Source: Teresa Doula

Thus childbirth became a very social event, where women close to the new mom would join the midwife in the home to cluck around, eat cake, drink and maybe lend a hand as the woman struggled. These women had a cute nickname, too: God sibs. Over time, the name morphed into a term you’re probably more familiar with: gossips.

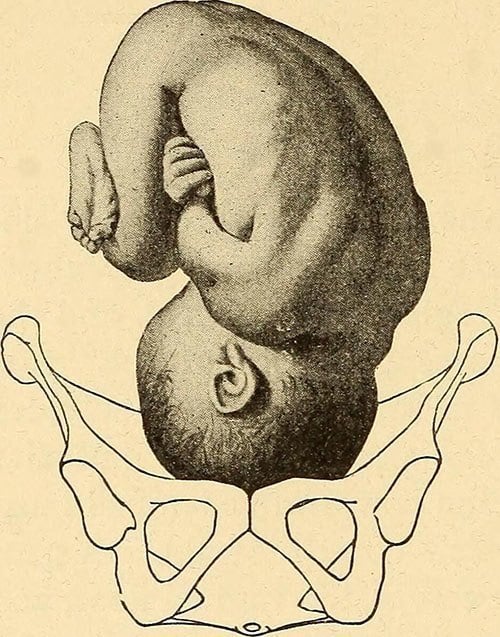

Towards the middle of the century, and after hearing horror stories of childbirth fatalities, a family known as the Chamberlens created a tool that they believed would change the birthing game forever. They created the obstetric tool commonly known as forceps, and they guarded their invention ferociously.

They would often attend births with the tool hidden under their cloaks, blindfolding the mother so that she wouldn’t see it, and bang pots and pans to disguise the sound of the tool (which they feared, if heard, could give away the key to its design). It would be another two hundred years before forceps became widely used, in part because the original prototype would be discovered in the floorboards of the Chamberlens’ house long after the inventors had died.

Source: Flickr Commons

Civil War Era

Source: Blogspot

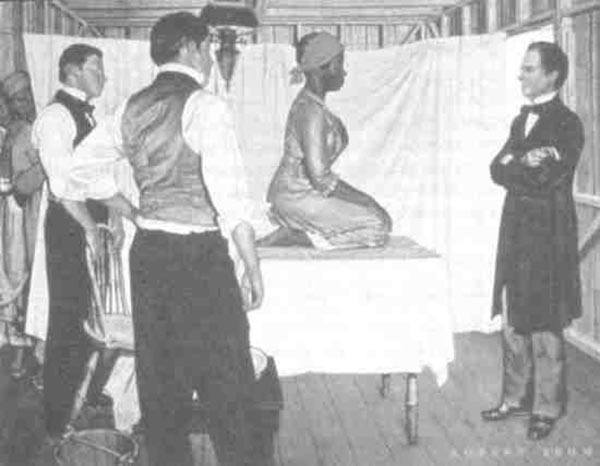

The next major renaissance in midwifery and obstetrics came from the Antebellum South. Young doctors practiced suturing techniques on female slaves and often bought slaves specifically with that purpose in mind. Subsequently many common gynecological procedures were developed during this time, most notably the treatment of fistulas, tears that can occur during childbirth and lead to complicated infections if they aren’t repaired.

Victorian England

Across the pond, London’s destitute women were dying in droves of something called “childbed fever”, or puerperal fever. “Lying-in” hospitals, which were also cropping up in many U.S. cities during this time, were almost entirely dedicated to delivering the poorest women’s babies. It’s an interesting corollary to modern times, when giving birth to a baby in the hospital can cost up to $32,000.

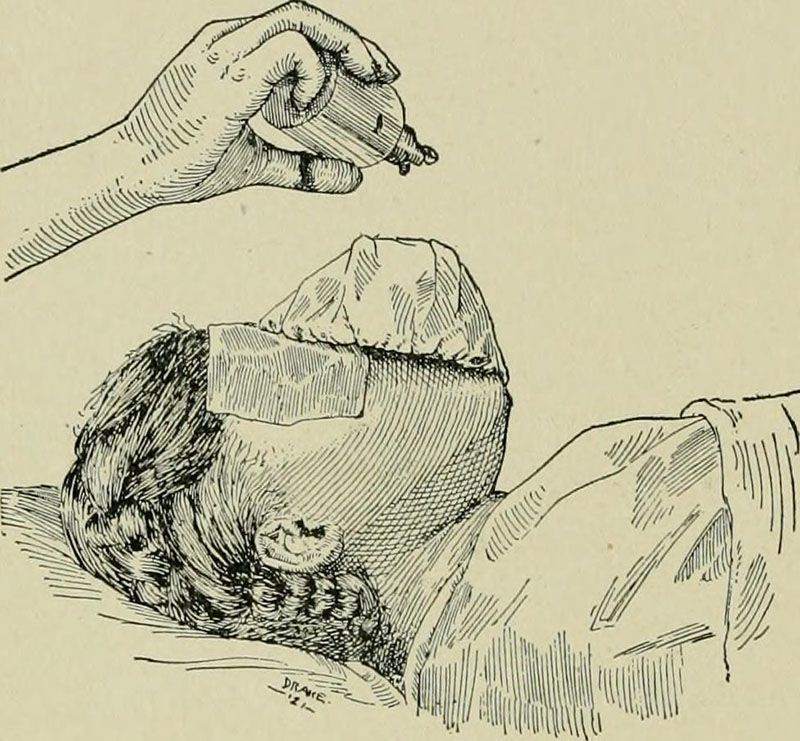

As women came into the hospital to give birth—only to die within a week—young doctors were scurrying back and forth between the birthing room and the morgue to suss out why these women had died. Unfortunately, they weren’t washing their hands after conducting the autopsies, and continued to spread the very bacteria that had killed the women on whom they were performing autopsies to the otherwise healthy women in the ward.

Source: Flickr Commons

Luckily for the women of London, “germ theory” (what we would call bacteriology today) began to take hold in city hospitals, and new medical students were being taught proper hand washing and sterilization techniques. Not surprisingly, as soon as these simple innovations were added to lying-in protocols, the occurrence of childbed fever dropped dramatically.

PR damage had already been done, however, and most upper class Victorian women wouldn’t be caught dead in a hospital to give birth. Queen Victoria herself gave birth at Buckingham Palace—though, not without help. It was she who blew the next winds of change into midwifery in the form of ether.

Source: Flickr Commons