The unbelievable story of Mount St. Helens and the most destructive volcanic eruption the U.S. has ever seen. Plus: the chances it'll soon erupt again.

USGSMount St. Helens on May 17, 1980, one day before the eruption.

For 123 years, Mount St. Helens was quiet. Then, in March 1980, the volcano in Washington state began to rumble. It erupted on May 17, 1980, forever dividing the history of region into two parts: Mount St. Helens before and after the catastrophic eruption.

In the aftermath, the area surrounding the volcano dramatically changed. Forests that had been there for over a century disappeared in the blink of an eye; thousands of animals and millions of fish perished; and the region’s beloved Spirit Lake was consumed by ash and debris.

But in the wake of destruction that rained down, new life grew too.

Mount St. Helens Before The Eruption

Mount St. Helens, a volcano that belongs to the Pacific Ocean’s “Ring of Fire,” had known its fair share of eruptions. The mountain had formed over the last 2,200 years, and had had at least nine significant eruptions before May 1980. But the last significant eruption had been in 1857 — 123 years earlier.

U.S. Forest ServiceThe natural beauty of Mount St. Helens — seen here before the May 1980 eruption — had long drawn campers, hikers, and more permanent settlers.

In the interim, nature around the mountain had flourished. Hundreds of miles of old-growth forest stretched out from its base, with trees like Douglas firs, Pacific silver firs, and mountain hemlocks providing dense forest cover for dozens of species of small mammals like flying squirrels.

Mount St. Helens before the eruption was also home to Spirit Lake, a popular tourist destination that drew campers and hikers. People admired the lake, which plunged to 200 feet at its depths, for its clear blue waters.

The beauty of the region drew more permanent settlers as well. Thousands had settled in the surrounding Skamania County, which boasted a population of almost 8,000 people by 1980, according to the U.S. Census.

But living near Mount St. Helens also meant living near constant danger. The volcano, though quiet for over a century, was considered a “Sleeping Giant.” And in March 1980, the “Giant” began to wake up.

The Eruption Of Mount St. Helens

On March 20, 1980, seismic activity was detected at Mount St. Helens for the first time in 123 years. A 4.2 earthquake rocked the mountain, quickly followed by a series of microquakes. According to a report compiled by the state of Washington in June 1980, new craters began to crack open, releasing plumes of ash and steam that rose thousands of feet into the air.

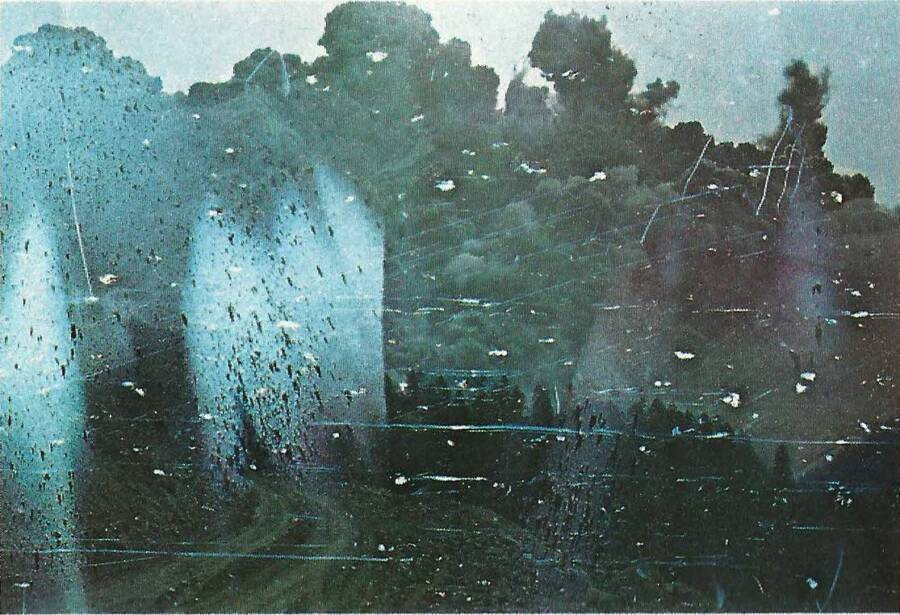

Public DomainA phreatic eruption at Mount St. Helens, when steam is released, shortly before the volcanic eruption.

As Fox News Weather reports, this foreboding development prompted evacuations within a 15-mile radius of the volcano, as well as roadblocks. But though the mountain started to form a rapidly growing bulge, the mountain was fairly quiet in April and early May. Some officials even started talking about reopening certain areas for Memorial Day, even as scientists warned that the danger of a catastrophic volcanic eruption had not yet passed.

Then, on May 18, 1980, Mount St. Helens erupted.

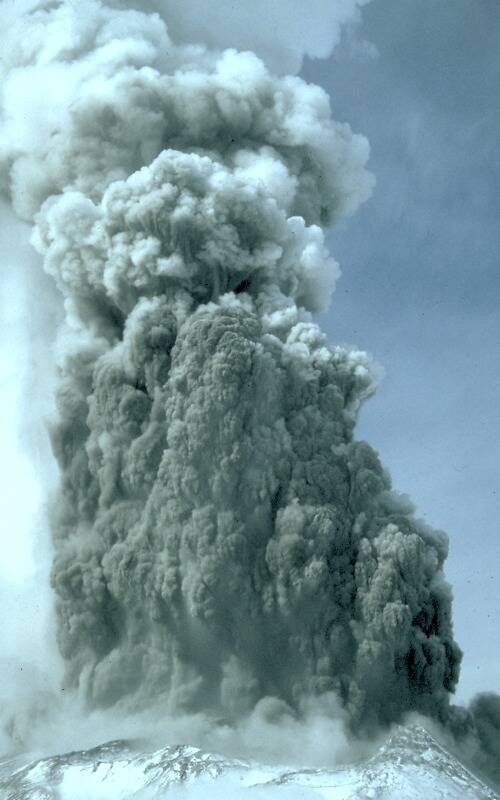

United States Geological SurveyThe eruption of Mount St. Helens on May 18, 1980.

The north face of the mountain collapsed, volcanic matter surged forward at a speed of 300 miles per hour, and an avalanche of molten debris (660 degrees Fahrenheit) punched through 17 miles of land in just three minutes.

Meanwhile, ash billowed 80,000 feet up into the sky, blotting out the sun and casting far-flung cities like Spokane (250 miles away) into total darkness.

Wikimedia CommonsOne of the eerie final photos of the Mount St. Helens eruption taken by photographer Robert Landsburg, one of the 57 people who died.

Mount St. Helens after the eruption was never the same again.

Mount St. Helens After The Eruption

The eruption of Mount St. Helens destroyed 230 square miles of forests and obliterated all trees within six miles. It killed 57 people, some 7,000 big game animals, and 12 million young salmon, as well as almost all the birds and small mammals in its path. The United States Geological Survey additionally reports that the eruption also destroyed 27 bridges, 185 miles of highways and roads, 15 miles of railways, and more than 200 homes.

Spirit Lake was also buried beneath tons of ash, tree debris, and mud.

In the days afterward, the area around Mount St. Helens looked like another planet. Everything was gray and draped in ash. Flat gray earth stood where forests had once thrived, and the air was still and quiet without birdsong.

U.S. Forest ServiceThe same plot of land near Mount St. Helens in 1979 (left) and 1981 (right).

“The initial impression was that nothing or few things would survive,” Charlie Crisafulli, an ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station and one of the first scientists to arrive on the scene after the eruption, recounted to CBS News in 2015. “It looked like everything had been destroyed, that all vestiges of life had been snuffed out.”

But despite the awesome destruction of the eruption, life on the mountain slowly crept back. Ants and gophers — who had survived by burrowing in the earth — began to emerge, and vibrant flowers like the purple-blue prairie lupines began to sprout. Robins, attracted by the open space, flocked to the region, and elks began to return to take advantage of the new plant life.

USGSAvalanche lilies on Mount St. Helens in June 1980, just a month after the volcanic eruption.

Meanwhile, the landscape around Mount St. Helens changed in other ways as well. The eruption had created 150 new lakes and ponds, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and Spirit Lake slowly came back to life. Wider, shallower, and warmer than before, it has fostered different kinds of species, like rainbow trout. Dead trees, which float in the lake to this day, also created a “floating ecosystem” for different kinds of insects.

Though some species have not returned to the area — like flying squirrels — researchers have been overall impressed with the resilience of the Mount St. Helens ecosystem. And because Congress allocated 110,000 acres of wildlife around the mountain for the National Volcanic Monument, nature there has been allowed to thrive unmolested.

That is, until the next time Mount St. Helens erupts.

For more incredible then and now photography, check out how much the world’s most densely populated city has changed, and the sad evolution of what was once the world’s most beautiful train station.