Three days after the devastation of Hiroshima, U.S. forces carried out the atomic bombing of Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. The attack killed 70,000 in an instant and remains fiercely debated to this day.

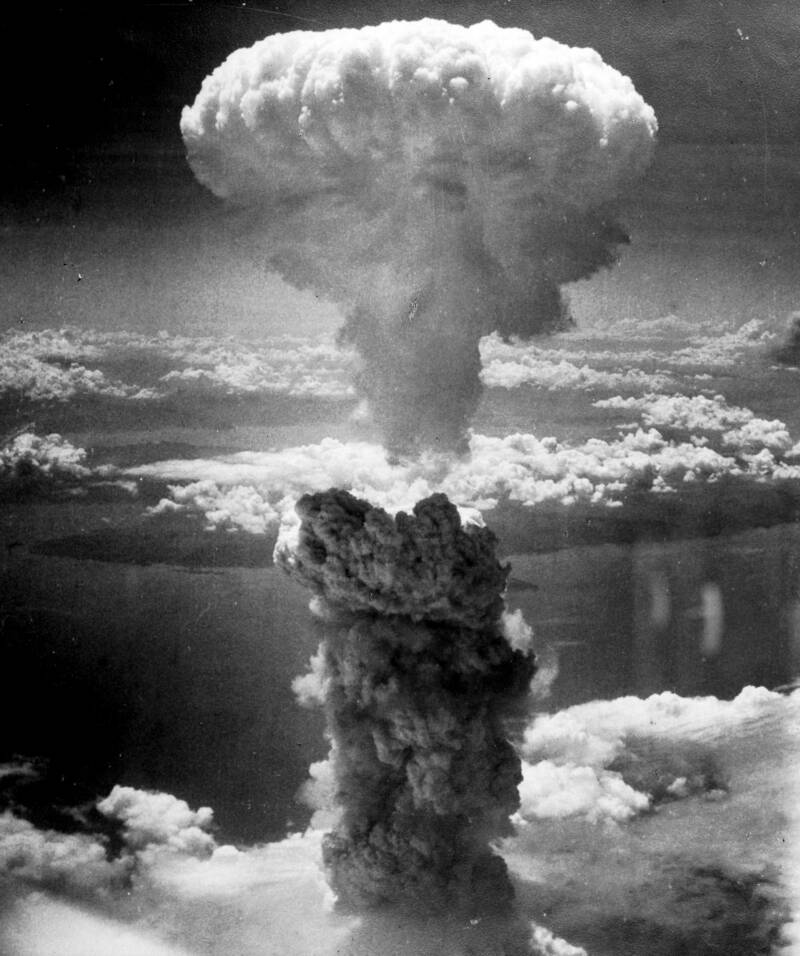

Wikimedia CommonsThe atomic cloud rises over the city after the Nagasaki bombing on August 9, 1945.

On the morning of August 9, 1945, the United States dropped the second atomic bomb ever used in warfare on the city of Nagasaki, Japan. The blast created temperatures hotter than the Sun, sent a mushroom cloud more than 11 miles into the air, and killed an estimated 70,000 or more people in an instant. As one survivor later recalled, upon emerging from hiding just after the blast, “I will never forget the hellscape that awaited us.”

But it almost didn’t happen.

In history class, we’re taught that the U.S. dropped two bombs — “Fat Man” and “Little Boy” as they were so called — in succession, one on the city of Hiroshima, the other on Nagasaki three days later. And while this is true, most fail to regard these two bombings as two distinct missions — one of which was not in the original plan.

While the Nagasaki bombing often gets lost in the shadow of the Hiroshima attack today, the true story of how the Nagasaki blast happened — and whether it should have happened at all — often goes overlooked.

The Preparations For The Atomic Bombings

Wikimedia CommonsThe crew of the Enola Gay, the primary aircraft used in the Hiroshima bombing and a secondary aircraft used in the Nagasaki bombing.

The United States’ development and deployment of two atomic bombs heralded the end of World War II and the culmination of a race between the U.S. and the Germans to create these supremely powerful weapons.

Working in conjunction with allies from Canada and the United Kingdom, the U.S. atomic bomb effort (the Manhattan Project) took root in New Mexico’s Los Alamos Laboratory under the guidance of physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, with tests beginning in the early summer of 1945 after about four years of development.

Immediately, the military planned to unleash their new bombs on Japan, their remaining enemy in a war that was nearing its end. Top military officials quickly joined together to form a Target Committee, which would identify the most devastating places the bombs could be dropped — ideally destroying sites that contained munitions factories, aircraft manufacturers, industrial facilities, and oil refineries. Target selection was also based on the following criteria:

- – The target was larger than 3 mi (4.8 km) in diameter and was an important target in a large urban area.

– The blast would create effective damage.

– The target was unlikely to be attacked by August 1945.

Beyond the physical size of the area, the committee focused on selecting targets that held great meaning to Japan. The U.S. military wanted to devastate Japan in no uncertain terms — but they also wanted the atomic bomb’s blast to be so magnificent, so spectacular, that the entire world would be paralyzed by its power.

Thus the committee first settled on the cities of Kokura, Hiroshima, Yokohama, Niigata, and Kyoto. Nagasaki was not on the short list.

Finalizing The Locations For Destruction

Wikimedia CommonsNagasaki six weeks after the bombing.

Kyoto — chosen because of its military significance and its status as an intellectual hub of Japanese culture — was one of the first cities to be removed from the list. In his biography, Edwin O. Reischauer, an expert on Japan for the U.S. Army who was consulted as a part of the Target Committee’s search, mentioned that the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, probably saved Kyoto from being bombed.

He wrote that Stimson “had known and admired Kyoto ever since his honeymoon there several decades earlier,” and at his urging (directly to President Truman), Kyoto was removed from the Target Committee’s list.

In his diary, President Truman noted after this conversation:

“This weapon is to be used against Japan between now and August 10th. I have told the Sec. of War, Mr. Stimson, to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children. Even if the Japs are savages, ruthless, merciless and fanatic, we as the leader of the world for the common welfare cannot drop that terrible bomb on the old capital [Kyoto] or the new [Tokyo]. He and I are in accord. The target will be a purely military one.”

As the shortlist further dwindled down, Hiroshima emerged as a strong choice. Not only was it a Japanese military-industrial hub, at least 40,000 military personnel were stationed in or just outside of the city. Of all the major cities in Japan, it remained the most intact after the series of air raids, making it even more appealing. The population was around 350,000.

The committee added Kokura and the nearby city of Nagasaki as alternative targets, should something go wrong with the plan to drop the atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima, which would take place on August 6, 1945.

The Devastation Of Hiroshima And The Decision To Drop A Second Bomb

Bernard Hoffman/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesA man looks at the ruins of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall after the bombing. The structure was preserved and was later renamed the Genbaku Domu (Hiroshima Peace Memorial).

When the first atomic bomb, Little Boy, was dropped on the city of Hiroshima, it detonated with a blast equivalent to 16 kilotons of TNT. Temperatures reached higher than 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit and the light was brighter than the Sun.

The firestorm that came next caused the most deaths in the immediate aftermath of the Hiroshima blast. All told, the bomb killed 30 percent of Hiroshima’s population, some 80,000 people, and left upwards of 70,000 injured. Because the bomb slightly missed its original target and instead detonated above a hospital, it killed or injured 90 percent of the city’s doctors and 93 percent of its nurses, leaving few to tend to the wounded.

Alfred Eisenstaedt/Pix Inc./The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesA mother and child sit in the ruins of Hiroshima four months after the bombing.

In the days that followed, the U.S. military turned to their second choice, Kokura, as well as Nagasaki, one of the largest seaport cities in Japan. The latter produced some of the country’s most vital military supplies, including ships.

While Nagasaki was known to be an important city to Japan, it had evaded previous firebombing because it was very difficult to locate at night with military radar. Beginning on the first of August, the U.S. military dropped several small-scale bombs in the area, mostly hitting shipyards and beginning to chip away at the city’s sense of security after having been spared the blasts plaguing the rest of the country. Nevertheless, Kokura remained the primary target.

Meanwhile, American engineers completed the second atomic bomb, Fat Man, on August 8. President Truman had only stipulated that the pair of bombs be used on Japan as they became available, so the timing of the second bombing depended squarely on how soon the engineers could complete it. In a hurry to drop a second bomb, the U.S. planned to drop it just the day after it was finished.

The Fateful Bombing Of Nagasaki

Wikimedia CommonsThe mushroom cloud rose more than 11 miles into the sky following the bombing of Nagasaki.

The mission to drop Little Boy on Hiroshima went off basically without a hitch: the bomb was loaded, “weaponeers” prepped for their task, the target was located and, for the most part the bomb hit as directly as wind would allow.

The Nagasaki mission, however, seemed to go wrong right from the start — primarily because the planes were initially headed for Kokura.

As the B-29 flew into the night with 13 military personnel on board, something unexpected happened: the bomb armed itself, seemingly apropos of nothing. Grabbing the bomb’s manual, those on board clamored to figure out what had happened, and what they needed to do to be sure it did not detonate before they reached their target.

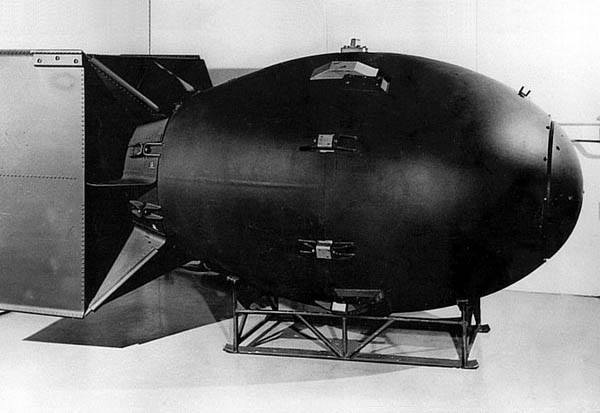

Wikimedia CommonsKnown as Fat Man, the plutonium bomb that was detonated over Nagasaki on August 9, 1945.

Exactly what transpired on this flight is not well-documented, except from what appears in the diaries of the men aboard the plane. Highly-edited versions appear in archival military reports. The personal accounts vary, depending on perspective.

Firebombing and cloud formation from the previous atomic bomb detonation just days earlier clouded the skies above Japan, in particular above Kokura. Mission pilots panicked, worrying that they were running out of time and fuel (which they were) and elected to forget about Kokura and head for the backup target of Nagasaki.

As they approached Nagasaki, the clouds parted, and the pilot radioed in that he could see the city. He was given the go-ahead.

As the plane carrying Fat Man — packed with 14 pounds of plutonium — flew over the city, no sirens warned civilians of the impending disaster. Officials thought the small number of planes on the bombing missions were just reconnaissance aircraft, so they sounded no alarm.

As Nagasaki resident Takato Michishita later recalled, it was “an unusually quiet summer morning, with clear blue skies as far as the eye can see.”

But then, the pilot of the Bockscar dropped the bomb out of the sky in silence, and 47 seconds later, it detonated.

Inside The “Hellscape” Created By The Nagasaki Bombing

Wikimedia CommonsA victim of the Nagasaki bombing who suffered burns in the ensuing firestorm.

Estimates say that the bomb instantly killed some 70,000 men, women and children. Only 150 were members of the Japanese military. The bomb injured 70,000 more, and radiation would continue to take the lives of those who had been there for decades.

Meanwhile, many who died in the immediate aftermath did so slowly and painfully. Though the firestorm burned many to death at once, many more suffered horrific burns that made the scene just after the blast especially nightmarish for survivors.

“As we sat there shell-shocked and confused,” survivor Shigeko Matsumoto recalled, “heavily injured burn victims came stumbling into the bomb shelter en masse. Their skin had peeled off their bodies and faces and hung limply down on the ground, in ribbons.”

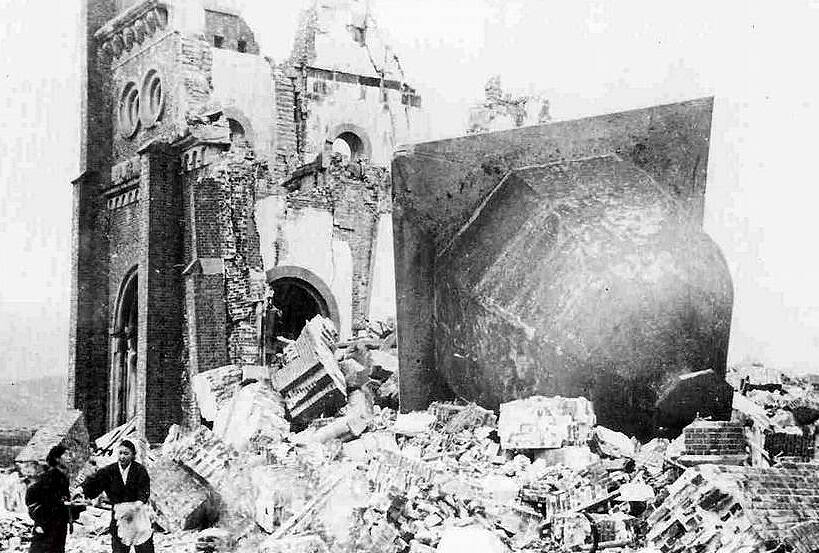

Wikimedia CommonsPeople walk among the ruins of Nagasaki’s Urakami Tenshudo church months after the bombing.

As another survivor, Masakatsu Obata, remembered:

“I encountered a coworker who had been exposed to the bomb outside of the factory. His face and body were swollen, about one and a half times the size. His skin was melted off, exposing his raw flesh. He was helping out a group of young students at the air raid shelter. ‘Do I look alright?’ he asked me. I didn’t have the heart to answer.”

Despite the macabre suffering of those on the ground, the Nagasaki bombing went largely overlooked beyond the city’s own borders.

As it happened, Soviet troops had advanced into Japan at the same time as the U.S. missions to drop the bombs — and it was this event that made headlines on August 8 and 9, not the bomb dropped on Nagasaki. In Truman’s subsequent radio address to Americans, he mentioned the atomic detonation on Hiroshima once, and did not mention Nagasaki at all.

To this day, the bombing too often goes overlooked. However, many who have taken a closer look believe that the bombing was not necessary at all.

The Complicated Legacy Of The Nagasaki And Hiroshima Bombings

Wikimedia CommonsThe view of the mushroom cloud over Nagasaki from the vantage point of one of the American B-29 bombers flying overhead.

By most mainstream Western accounts, which have continued to focus on the ethical justification for both atomic bombings, the events in Hiroshima and Nagasaki forced the Japanese military to surrender and brought World War II to a close.

However, some historians contend that the Japanese military wasn’t swayed toward surrender by the atomic bombings, but was instead much more scared of the Soviet invasion.

Meanwhile, Japanese history books teach that the U.S. government acted in what is termed “atomic diplomacy”: The U.S. intended to intimidate the Soviet Union with their weaponry, and the country of Japan was a casualty in what constituted the earliest stages of the Cold War.

Critics in both countries and elsewhere say that the attacks weren’t needed to end the war, targeted civilians as an act of terror, were in fact designed to intimidate the Soviet Union with U.S. nuclear power, and were carried out because the U.S. was able to dehumanize its non-white enemies in Japan.

As U.S. General Curtis LeMay, the man who relayed President Truman’s order to drop the bomb, later said, “If we’d lost the war, we’d all have been prosecuted as war criminals.”

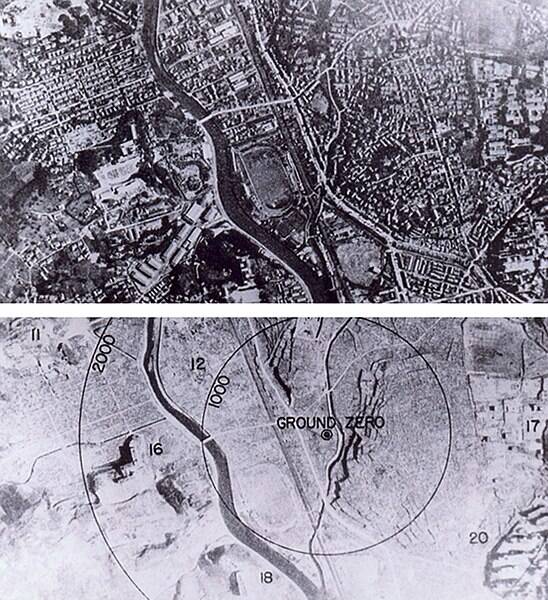

Wikimedia CommonsAerial views of Nagsaki before and after the atomic bombing.

No matter the lens one uses to look at the legacy of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, one thing is clear: The world has never been, and will never be, the same again.

And for some of those who lived through the Nagasaki bombing, we must do what we can to set the world back to the way it was. As Nagasaki survivor Yoshiro Yamawaki put it, “Weapons of this capacity must be abolished from the earth… I pray that younger generations will come together to work toward a world free of nuclear weapons.”

After this look at the Nagasaki bombing, see the nuclear shadows of Hiroshima’s victim that formed as the city was being destroyed. Then, learn the story of the USS Indianapolis, the ship that delivered the ingredients for the Hiroshima bomb before sinking in shark-infested waters.