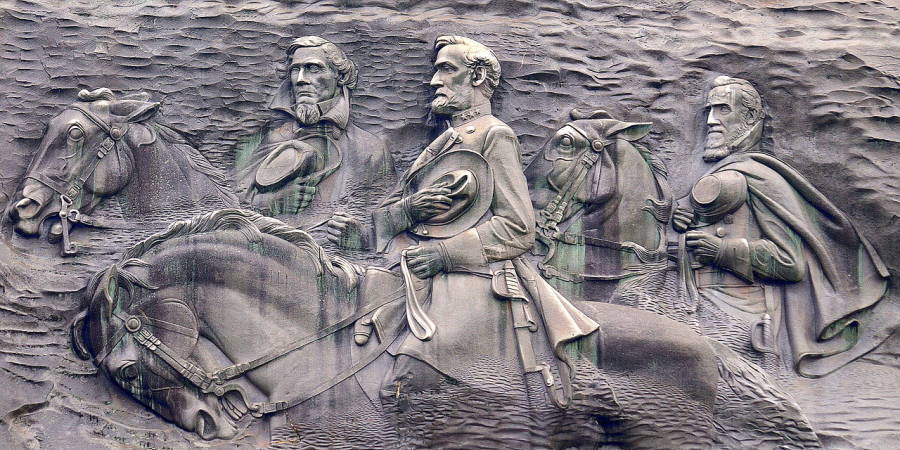

Stone Mountain Park's memorial is the largest high relief sculpture in the world. It's racist, bigoted history has critics calling for alterations or removal, particularly in the wake of recent race-motivated killings.

Image Source: Wikipedia

Stone Mountain Park in Atlanta, Georgia is one of the largest Confederate monuments in the United States. The granite carvings of Robert E. Lee, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, and Jefferson Davis cover over 17,000 square feet of mountain.

According to The Washington Post, it is the largest flat relief sculpture on the planet. At an altitude of 1,700 feet, the monument is certainly visible from a distance, and with the growth in white supremacist crimes across the country, its meres existence has become a point of debate.

The notion of ridding the country of this colossal outcropping has become more realistic in recent years, as Confederate monuments have already been removed in various states. Not to mention that Stone Mountain Park was created at the birthplace of the modern Ku Klux Klan, and currently still serves as a symbolic piece of iconography for white supremacists.

Stacey Abrams, former minority leader of the Georgia House of Representatives, called the monument “a blight on our state” during her time in office. Calls to remove the relic were greeted with vehement opposition at the time.

As it stands, the monument remains intact. Its history, and staunchly defended right to exist, is a thoroughly elucidating part of American history that might shock, distress, or surprise you.

The Ancient History Of Stone Mountain

Stone Mountain is a monadnock — an isolated mountain — that was created when a pocket of magma underground became trapped 300 million years ago and was pushed to the surface 15 million years ago.

According to The Smithsonian, Paleo-Indians gravitated toward the mountain as early as 4000 B.C. Archaeologists have based these early occupations at Stone Mountain from soapstone bowls and a variety of other artifacts discovered at the site. Researchers later found stone walls on the summit, which are estimated to date back to 100 B.C.

Wikimedia CommonsThe late 1800s saw the Stone Mountain granite quarries get thoroughly excavated by the Stone Mountain Granite and Railway Co. The stone was used all over the country, and even as far as Japan.

In 1869, the Stone Mountain Granite and Railway Co. decided to mine the mountain. Taken over by the Venable Brothers in 1882, the massive effort saw workers mine 200,000 paving blocks per day. These blocks were shipped across the U.S. and the world, and used in a variety of historic structures.

From the steps of the U.S. Capitol’s east wing and the locks of the Panama Canal, to the Arlington Memorial Bridge and the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, granite from Stone Mountain can be found all over the world. Dozens of post offices and courthouses in America used it in their construction.

In 1916, however, the gigantic structure would be adorned with a now-infamous carving that has been greatly contested in recent years.

The Ku Klux Klan

Atlanta Georgian newspaper editor John Temple Graves believed that the South needed and earned a monument to the heroes of its Confederacy. He argued for the cause in his paper on June 14, 1914.

“Just know, while the loyal devotion of this great people of the South is considering a general and enduring monument to the great cause ‘fought without shame and lost without dishonor,’ it seems to me that nature and Providence have set the immortal shrine right at our doors.”

Graves was an utter racist who argued a decade earlier that lynching black people was the most preventative method against rape, because “the negro is a thing of the senses…[and] must be restrained by the terror of the sense.”

Civil War widow C. Helen Plane read his call for a monument and agreed.

Wikimedia CommonsIt was William Simmons who introduced cross burning to the modern KKK. He was inspired by D.W. Griffith’s ‘Birth of a Nation.’ Seen here are Klan members burning a cross in Denver, Colorado. 1921.

The 85-year-old member of the Atlanta United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) was eager to honor the memory of her late husband and all other dead Confederate soldiers, and raised the prospect of a memorial in front of the city and state chapters of the UDC.

The organization firmly agreed, and settled on Mount Rushmore sculptor Gutzon Borglum as the right man for the job. Borglum’s initial idea was far more expansive than the proposition he was approached with. After visiting the site, the sculptor wanted to carve 700 to 1,000 figures across 1,200 feet.

Lee, Jackson, and Davis would be in the foreground while hundreds of Confederate soldiers comprised the background. This would be far more costly and time-consuming, of course, and require eight years and $2 million to accomplish.

“The Confederacy furnished the story, God furnished the mountain,” Borglum said in front of potential investors in 1915. “If I can furnish the craftsmanship and you will furnish the financial support, then we will put there something before which the world will stand amazed.”

Plane, meanwhile, secured some of the funding as well as a land lead from the Venable family. Patriarch Sam Venable invited Borglum — as well as founder of the modern KKK, William Simmons — to his property in the fall of that year.

The resurgent KKK was founded at the top of Stone Mountain on Nov. 25, 1915. The group had largely dissipated in the late 1800s, but that night, over 12 men gathered to start anew. With D.W. Griffith’s Birth Of A Nation as their inspiration, they burned a cross and pledged allegiance to the Klan.

Wikimedia CommonsProperty owner Sam Venable invited both sculptor Gutzon Borglum and founder of the modern KKK, William J. Simmons (pictured) to his property in 1915. Simmons and 12 men burned a cross and pledged allegiance to the KKK on Nov. 25, 1915 atop the mountain.

Borglum started considering implementing the KKK into his new project. Plane wrote:

“The Birth of a Nation will give us a percentage of next Monday’s matinee. Since seeing this wonderful and beautiful picture of Reconstruction in the South, I feel that it is due to the Ku Klux Klan which saved us from Negro domination and carpet-bag rule, that it be immortalized on Stone Mountain. Why not represent a small group of them in their nightly uniform approaching in the distance?”

Borglum agreed that the racist group should be represented in the memorial, but fortunately, his work was extensively delayed by the First World War — before a disagreement with management had him exit the project altogether in 1925. He went on to work on Mount Rushmore from 1927 to 1941.

In the meantime, the KKK grew to more than four millions members. The group conducted its infamous march on Washington, D.C. in 1925.

The Civil Rights Movement

The Venables had granted the UDC 12 years to complete the project, and with only three years to go before expiration of the contract, a second sculptor was hired. Unfortunately for Augustus Lukeman, he wasn’t able to remove Borglum’s work and make headway on his own before he was forced to exit the project in 1928.

With the land deed contract expired, the Venable family reclaimed its property — which remained untouched for 36 years. Georgia state tried to get Stone Mountain recognized by the National Park Service, but the latter rejected the filing due to the granite quarry and incomplete carvings tainting the mountain’s value.

The 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision firmly stated that segregated schools were unconstitutional, yet Georgia governor Marvin Griffin promised his constituents that “there will be no mixing of the races” in his 1955 inaugural address.

Wikimedia CommonsVisitors situate themselves in Stone Mountain Park and prepare for the nightly laser show. Both the memorial and the park’s train can be seen in the distance.

He then purchased Stone Mountain for $1 with the help of the Georgia General Assembly — and made the Stone Mountain Memorial Association a state authority. This allowed him to appoint whomever he wanted to its board of directors, and paved the way to construct the troubling Confederate monument without a fight.

“State politicians formed Stone Mountain Park as part of an effort to ground the white southern present in images of the southern past, a sort of neo-Confederatism, and halt nationally mandated change in the region,” wrote historian Grace Elizabeth Hale.

“For the governor and other supporters of the new plans, the completion of the carving would demonstrate to the rest of the nation that ‘progress’ meant not black rights, but the maintenance of white supremacy.”

Thus, work resumed after a nearly 40-year break in 1964 with Walter Kirkland Hancock selected as the sculptor in charge. A dedication ceremony was held on May 9, 1970, with the memorial seeing completion in 1972.

The Stone Mountain Sculpture And Its Backlash

The Stone Mountain memorial is a rather impressive piece of art, though its subject matter is an upsetting reminder of America’s cruelty and injustices. The fine detail (eyebrows and belt buckles visible) and the sculpture’s sheer size — an adult male could stand in one of the three horse’s mouths — is still remarkable craftsmanship.

Of course, even though it became the largest relief sculpture in the world, it was built as a tribute to the horrors of American slavery. As such, its grandeur is more nauseating than awe-inspiring. In its early days, the park beneath even included a plantation replica — replete with slave quarters described as “neat” and “well furnished” in the park’s promotional pamphlets.

The slaves, meanwhile, were called “hands” and “workers.”

As such, the Stone Mountain Park memorial has been staunchly criticized in recent years, particularly as the nation’s divisiveness comes into stark relief and mass shootings by white supremacists continue to increase. The clearest reassessment came after the violence at Charlottesville, of course.

Lt. Gov. Casey Cagle, of course, firmly disagreed with recent proposals to sandblast the monument or add black American historical figures to it in an attempt to balance history.

“Instead of dividing Georgians with inflammatory rhetoric for political gain, we should work together to add to our history, not take from it,” he said.

Part of 2001 Georgia state law — passed during the very same discussions that rid the Georgia flag of its Confederate Stars and Bars — vehemently secures carvings like the Stone Mountain mural from being “altered, removed, concealed, or obscured in any fashion…for all time.”

In 2015, park officials agreed to plan on installing a working “freedom bell” atop Stone Mountain in honor of Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. After all, it was his 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech that included the following request of us all:

“Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia.”

Hopefully, that day will actually come.

After learning about Stone Mountain Park and its Confederate history, read about the tragic story of Jonestown massacre, modern history’s largest mass “suicide.” Then, take a look at 28 shocking photos of modern history’s most infamous assassinations.