During the Holocaust, 130,000 female prisoners pass through the gates of Ravensbrück — most of whom never walked back out.

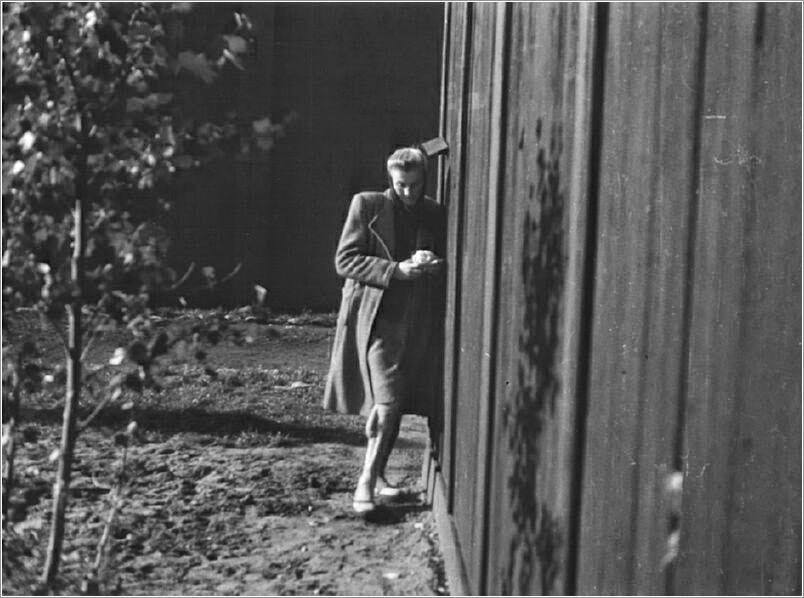

Rescued women from Ravensbrück.

Among the horrors of Nazi concentration camps like Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Dachau, and Mauthausen-Gusen, the story of Ravensbrück often gets overlooked.

Perhaps it’s because it was one of the only camps exclusively for female prisoners — perhaps a strange concession to propriety in the middle of a genocide that killed men, women, and children indiscriminately — and people mistakenly assume that a women’s camp was a kinder, gentler place.

Or perhaps it’s because the camp was almost immediately sealed off in East Germany after its liberation by Soviet forces, meaning it would be years before the Western world glimpsed its facilities.

It doesn’t help that it wasn’t photographed upon liberation. Unlike Bergen-Belsen or Dachau or Buchenwald, its horrors weren’t recorded by the professional photographers who accompanied Allied troops in the war’s final days. But the story of Ravensbrück concentration camp is well worth remembering.

The following images of Ravensbrück women’s concentration camp present a stark image of the brutality of the Nazi regime — but, more than that, they are a testament to the strength of these women, who would make jewelry, write comic operettas about camp life, and organize secret education programs to remind themselves of their humanity.

Incredibly, in some photos, the female inmates even muster the energy and the courage to smile.

Who Was Sent To Ravensbrück?

World War II saw 130,000 female prisoners pass through the gates of Ravensbrück — most of whom never walked back out.

What's surprising is that a relatively small number of those women were Jewish. Surviving records suggest that during the camp's operating years (May of 1939 through April of 1945), only 26,000 of the inmates were Jewish.

So who were the camp's other female prisoners?

Some had resisted the Nazi regime; they were spies and rebels. Others were scholars and academics who had openly supported socialism or communism — or put forward other opinions Hitler's government considered dangerous.

The Romani, like the Jews of Europe, were never safe where Nazis walked, and neither were prostitutes or Jehovah's Witnesses.

Other women simply didn't meet German expectations of femininity — this group included lesbians, the Aryan wives of Jews, the disabled, and the mentally ill. They, along with the prostitutes, were made to wear a black triangle badge that marked them as "asocial." Criminals, by contrast, wore green triangles, and the political prisoners red.

Jewish inmates, already familiar with the star badge that had singled them out prior to incarceration, were now assigned yellow triangles.

The more boxes you checked, the more badges you got, and the worse your fate was likely to be.

There were no exceptions, and there was no mercy. Whether a woman was pregnant or clutching toddlers didn't matter to the Gestapo; the children would follow their mothers into the camp. Almost none survived.

When all was said and done, the women of Ravensbrück had almost nothing in common. They came from all over Europe, wherever German troops roamed, and spoke different languages: Russian, French, Polish, Dutch. They had different socioeconomic backgrounds, different levels of education, and different religious views.

But they did share one thing: the Nazi party considered every single one of them "deviant." They were not part of Germany's glorious future, and everything about camp life was designed to leave them in no doubt about where they stood.

What Was Life Like At Ravensbrück?

When Ravensbrück was built on the orders of Heinrich Himmler in 1938, it was almost picturesque.

Conditions were good, and some prisoners, coming from the poverty of the ghettos, even expressed wonder at the manicured lawns, peacock-filled birdhouses, and flowerbeds lining the great square.

But behind the pretty façade was a dark secret — one Himmler was fully aware of. The camp had been built far, far too small.

Its maximum capacity was 6,000. Ravensbrück blew past that cap in just eight months, and some estimate that the camp once held as many as 50,000 prisoners at one time.

Barracks meant to accommodate 250 women had to fit as many as 2,000; even sharing beds wasn't enough to keep many off the floor, and blankets were scarce. Five hundred women shared three doorless latrines.

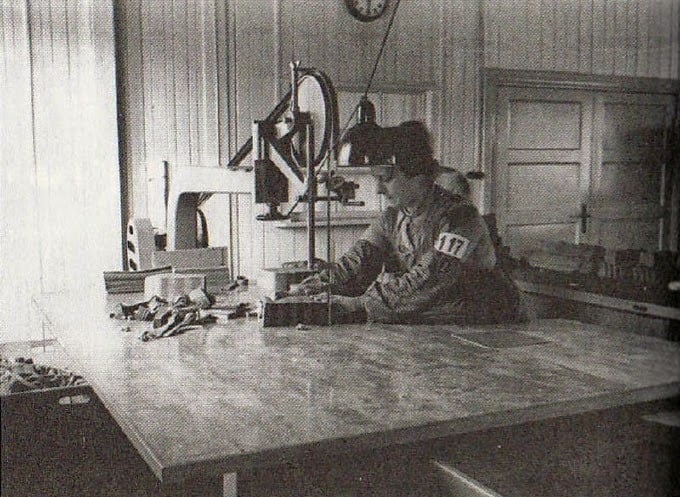

The results of overcrowding were disease and famine, both exacerbated by grueling manual labor. The women woke before 4:00 a.m. to build roads, pulling paving rollers like oxen before the plow. When inside, they spent long shifts bent over the electrical components of rockets, and in drafty, poorly lit halls, they sewed uniforms for prisoners and coats for soldiers.

They were only spared work on Sundays, when they were permitted to socialize.

Medical Experimentation And The Women Who Ran The Concentration Camp

One of the most confusing things about Ravensbrück is why it existed at all. Other camps housed both female and male prisoners. So why bother to create an all-women camp?

Some have suggested that Ravensbrück was created in part as a training ground for female prison guards, known as Aufseherinnen.

Women could not belong to the SS, but they could hold auxiliary roles — and the Ravensbrück facility trained thousands of women for guard duty in concentration camps across Germany.

They were no better than their male counterparts. Some said they were worse, because success as a guard offered them a rare opportunity for status and recognition in a deeply patriarchal regime — and they fought hard for it. Every step they took forward came at the expense of the inmates they oversaw.

They punished disobedient prisoners without mercy, locking them in solitary confinement, whipping them, and occasionally setting the camp's dogs on them.

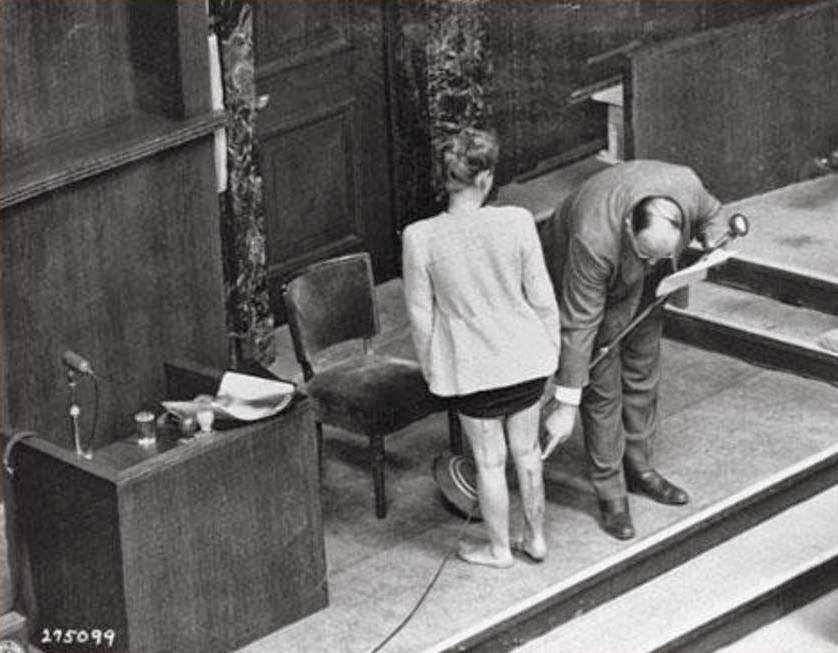

But that wasn't the worst that inmates faced. Eighty-six prisoners, most of them Polish, became known as the Ravensbrück "rabbits" when camp doctors selected them for medical experimentation.

The medical team was interested in the efficacy of antibacterial drugs known as sulfonamides in treating infections on the battlefield, especially gangrene. To that end, they infected patients, cutting deep into muscle and bone to deposit deadly bacteria on splinters of wood and glass.

But the doctors didn't stop there. They were also interested in the possibility of bone transplants and nerve regeneration. They conducted amputations and forced transplants, killing many of their "rabbits" in the process. Those who survived did so with permanent damage.

The doctors also practiced sterilization techniques, focusing on Romani women who agreed to the operation on the condition that they would be released from Ravensbrück. The doctors performed the surgeries, and the women remained behind bars.

The Final Days And The Liberation Of Ravensbrück

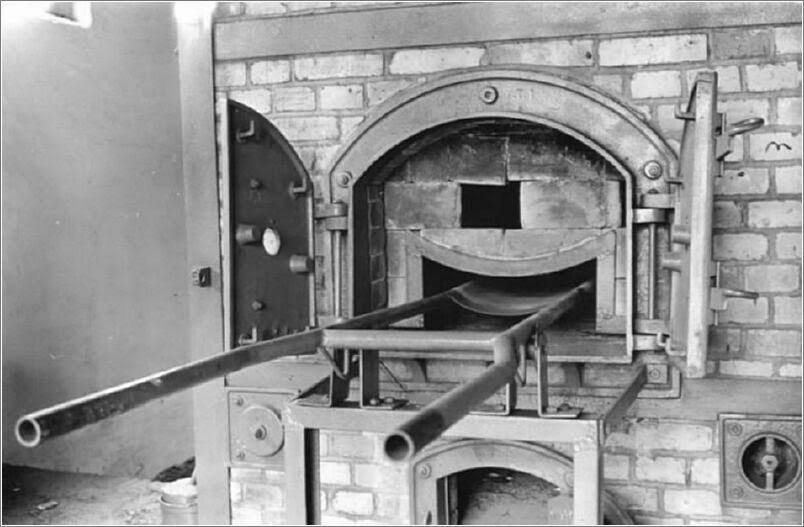

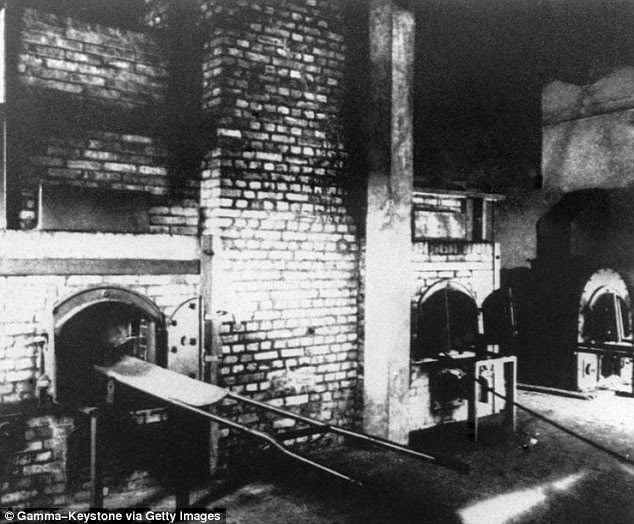

For much of the war, the Ravensbrück facility did not have a gas chamber. It had outsourced its mass executions to other camps, like the nearby Auschwitz.

That changed in 1944 when Auschwitz announced it had reached maximum capacity and closed its gates to new arrivals. So Ravensbrück constructed its own gas chamber, a hastily built facility that was used immediately to put to death 5,000 to 6,000 of the camp's prisoners.

In the end, Ravensbrück killed between 30,000 and 50,000 women. They met their ends at the hands of brutal overseers and experimenting doctors, froze and starved to death on cold earth floors, and fell victim to the diseases that plagued the overcrowded barracks.

When the Soviets liberated the camp, they found 3,500 prisoners clinging to life. The rest had been sent on a death march. In total, just 15,000 of the 130,000 prisoners who came to Ravensbrück lived to see its liberation.

The women who survived told stories of their fallen comrades. They remembered little forms of resistance and small moments of joy: they sabotaged rocket pieces or sewed soldiers' uniforms to fall apart, held secret language and history classes, and swapped stories and recipes most knew they would never make again.

They modified records and kept their friends' secrets — and even ran an underground newspaper to spread word of new arrivals, new dangers, or small causes for new hope.

Their ashes now fill Lake Schwedt, on whose shores the women of Ravensbrück made their last stand.

For more on the Holocaust, see our poignant gallery of Holocaust photos and the story of Stanislawa Leszczyńska, the woman who delivered 3,000 babies at Auschwitz. Then, read about the fearsome concentration camp guard known as Ilse Koch.