On April 15, 1846, the 87 pioneers of the Donner Party left Springfield, Illinois for California — but their journey ended in tragedy when they became snowbound in the Sierra Nevadas.

At the outset of their fateful journey in 1846, the pioneers of the Donner Party were just like so many other American settlers heading westward in the mid-19th century. Led by Jacob and George Donner, along with James Reed, they gathered in Springfield, Illinois in April 1846 and prepared to set out.

But unlike most westward pioneers, the Donner Party decided to take a supposedly shorter — yet untested — route to California.

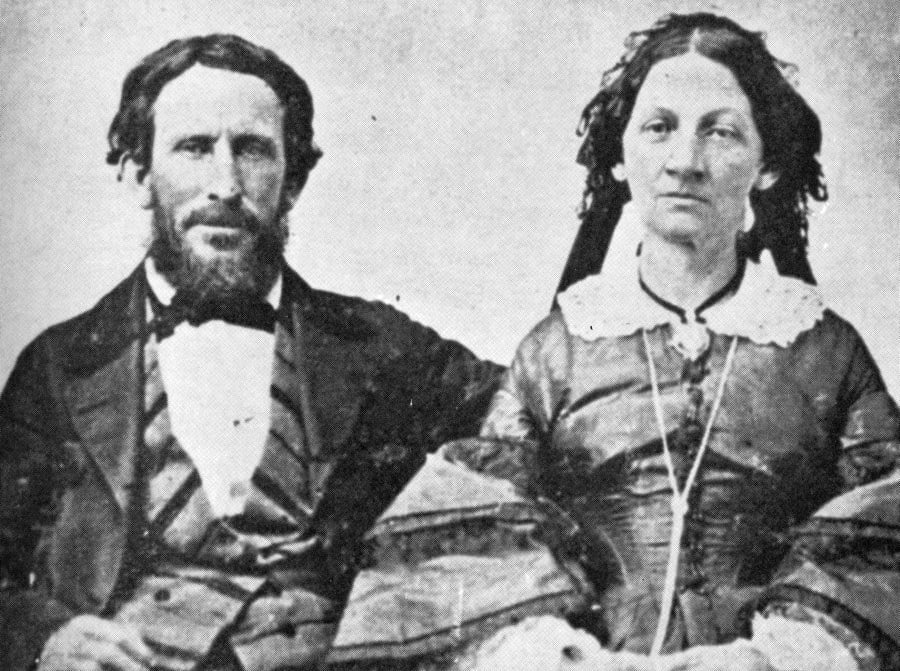

Wikimedia CommonsJames Reed, one of the three leaders of the Donner Party, with his wife Margret. Both were among the survivors.

Tragically, the route proved not only more arduous, but fatal. The Donner Party took so long trying to navigate their shortcut that they didn’t reach California’s Sierra Nevada mountains until winter. There, heavy snowfall trapped them near Truckee Lake.

Unable to move forward or back, the Donner Party quickly ran out of food. It didn’t take long for the social order to break down and for the pioneers to succumb to their hunger and resort to eating each other.

To this day, what happened to the Donner Party at Truckee Lake casts a long, macabre shadow over American history. This is the full story of the Donner Party’s doomed journey west.

The Donner Party Begins Its Journey To California

After a stop in Independence, Missouri to buy provisions and gather the full group, the Donner Party headed west on May 12, 1846. Led by two brothers, Jacob and George Donner, and an Irish businessman named James Reed, the party of 87 pioneers included men, women, and many young children.

By then, however, they’d already made a fatal mistake. Simply put, the Donner Party left too late.

Pioneers like them were supposed to follow a rigid schedule, leaving in mid to late April to ensure that their pack animals had ample grass to eat during the journey before the coldest months arrived. Leaving any later than mid-April meant risking that they’d still be traveling come winter.

“I am beginning to feel alarmed at the tardiness of our movements,” one member of the party, Edwin Bryant, wrote, “and fearful that winter will find us in the snowy mountains of California.”

Perhaps well-aware of their late start, the pioneers decided they’d take a shortcut called the Hastings Cutoff. Though most wagon trains looped north through Iowa, a guidebook author named Lansford Hastings suggested a more direct route existed. Naturally, he named the route after himself.

But there was just one problem — Hastings had never actually explored his own route. One of James Reed’s friends told him as much and begged him not to take the Donner Party along the untested route.

“Don’t take this shortcut!” Reed’s friend warned him. “Lansford Hastings doesn’t know what he’s talking about. He, in fact, has never taken this cutoff himself.

“I advise you strongly, don’t take it. Stick to the known California trail. Don’t take this shortcut that’s going to save you time, because it won’t.”

Tragically, Reed didn’t heed his friend’s advice. Instead of turning north, the Donner Party continued due west — and toward their doom.

Why The Hastings Cutoff Was A Shortcut To Damnation

Wikimedia CommonsThe Donner Party unfortunately opted for an enticing new route named after an unscrupulous guidebook author named Lansford Hastings.

Once on the Hastings Cutoff, it didn’t take the Donner Party long to realize their mistake. Instead of walking the well-trod paths of the California Trail, they had to cross the Wasatch Mountains and hike across the Salt Lake Desert.

Navigating the Hastings Cutoff was bad enough on its own. The nonexistent trail meant that the pioneers had to cut a path in the wild so that their wagons could get through. And many almost died of thirst during the five-day crossing of the salt desert.

But the worst part of the Hastings Cutoff was that it stole precious days from the Donner Party’s journey. This delay, plus their late departure, meant that they arrived at the Sierra Nevada mountains by early November. Had they left even a week earlier, they may have made it through the mountains.

Instead, they got stuck in a blizzard.

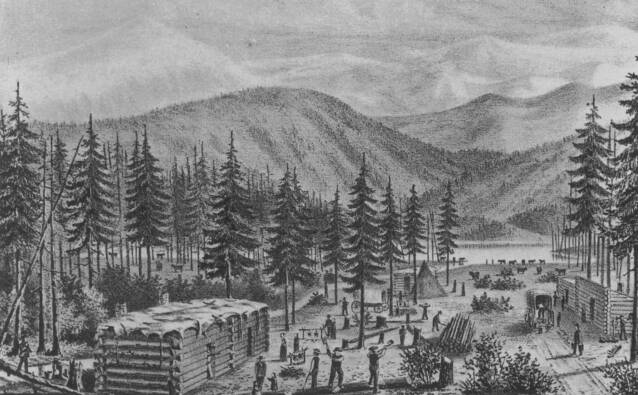

Library Of CongressPart of the landscape where the party was stranded. The height of the tree stumps indicates the height of the snow.

“All I could see was snow everywhere,” one Donner Party survivor later wrote. “I shouted at the top of my voice. Suddenly, here and there, all about me, heads popped up through the snow. The scene was not unlike what one might imagine at the resurrection when people rise up out of the earth. The terror amounted to panic. The mules were lost, the cattle strayed away, and our further progress rendered impossible.”

At this point, the Donner Party had just 100 miles to go. But with snowdrifts as tall as 25 feet, it was impossible to move forward. Instead, they set up camp at Truckee Lake. And they hoped to survive the long, cold winter.

The Donner Party Becomes Trapped In The Sierra Nevadas

Wikimedia CommonsTruckee Lake has since been renamed Donner Lake. Seen here is the Donner Lake Pass, photographed during the King Survey in the 1870s.

Trapped in the Sierra Nevadas, the Donner Party ate everything they could.

Because they’d already used up most of their rations on the long journey, they first killed their pack animals. To stretch out the meal, they sucked bone marrow and tried to make an edible paste from the animal hides.

Next, the Donner Party killed field mice. Then they killed and devoured their loyal dogs. Lacking any more animals to eat, the frantic pioneers chewed on pine cones and tree bark.

It wasn’t enough. And it didn’t escape anyone’s attention that there was an alternative food source nearby — the bodies of those who had perished, whom the pioneers had buried in a snowbank.

Diaries and letters written by the Donner Party survivors make it clear: the pioneers succumbed to their hunger. Deep into their desperate winter, the Donner Party’s members began resorting to eating each other.

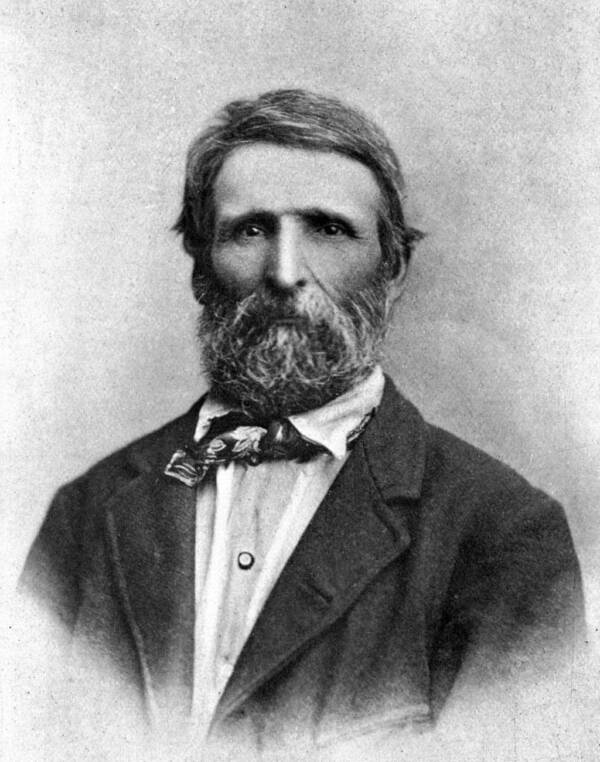

Wikimedia CommonsJust before completing their 2,500-mile journey from Illinois to California in 1846, the pioneers of the Donner Party became stranded in the Sierra Nevadas.

In one account, a young woman named Sarah Murphy Foster had hardly begun mourning her brother, Lemuel, when she realized that other pioneers were eating his heart.

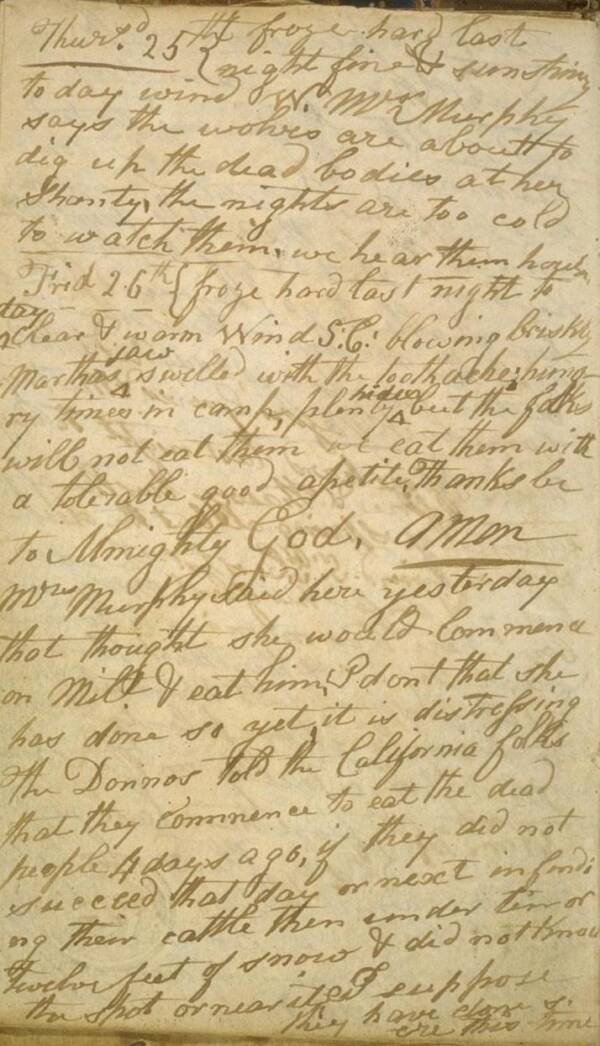

In another, Patrick Breen recorded in his diary that: “Mrs Murphy said here yesterday that thought she would Commence on Milt & eat him. I dont that she has done so yet, it is distressing.”

And when wolves began to sniff around the snowbound graves of the dead pioneers, one pioneer wrote in her diary: “Perhaps God sent the wolves to show Mrs. Murphy and also Mrs. Graves where to get sustenance for their dependent little ones… Was it culpable, or cannibalistic to seek and use the only life-saving means left them?”

For the most part, Donner Party members were determined to only eat people who had already died. But there were two tragic exemptions.

The Forlorn Hope Murders

On Dec. 16, a group of the strongest members of the Donner Party decided they’d try to get help. Their party — later called “Forlorn Hope” — included two Native Americans named Salvador and Luis.

Wikimedia CommonsAn 1880 illustration of the Truckee Lake camp, based on descriptions by Donner Party survivor William Graves.

The Native Americans had joined up with the Donner Party shortly before the blizzard trapped everyone in the Sierra Nevadas. They set out with the pioneers in December in hopes of finding rescue.

But after days on the march, the Forlorn Hope party found nothing but more snow. And they — already starving — began to get hungry.

When one of the men quietly warned Luis and Salvador that the others might kill them to eat, the two Native Americans fled.

“Some time during the night of the fourth, the Indians left them; no doubt fearful to remain, lest they might be sacrificed for food,” explained John Sinclair, a Californian who published a report on the Donner Party.

Luis and Salvador were right to flee. The pioneers quickly followed their trail in the snow. Once they found the Native Americans, collapsed in exhaustion, they killed them.

Wikimedia CommonsThe starving members of the Donner Party barely made it through the winter at Truckee Lake.

Donner Party member William Foster shot them both in the head, after which they were chopped up, cooked, and consumed by the others. Their deaths mark the only time that the Donner Party killed someone to eat.

Other Donner Party stories emphasize the fact that they only ate people who were already dead.

But although their journey was horrific, the Forlorn Hope party did succeed in their goal. After a month, they stumbled onto a ranch in California — and alerted the world to the horror unfolding in the mountains.

The Donner Party’s Worst Horrors At Truckee Lake

In all, it took four “relief” teams two months to rescue survivors of the Donner Party. And each relief team brought back harrowing stories about what the Donner Party had done during their desperate final chapter.

One man described seeing a “revolting and appalling spectacle” at Truckee Lake that included human skeletons in “every variety of mutilation.”

Another account claimed to have seen children “sitting upon a log, with their faces stained with blood, devouring the half-roasted liver and heart of the father.” This account went on to describe “hair, bones, skulls, and the fragments of half-consumed limbs” around the fire.

And one rescue party insisted that they’d seen a survivor, Jean Baptiste Trudeau, holding a human leg when they arrived at Truckee Lake.

Wikimedia CommonsOut of all the stories of the Donner Party, perhaps none is more chilling than that of Jean Baptiste Trudeau.

Trudeau himself later admitted to eating other Donner Party members. In a conversation with H.A. Wise, who published one account of the tragedy, Trudeau allegedly confessed to eating both Jacob Donner and his four-year-old son. Wise said that Trudeau told him, “[I] eat baby raw, stewed some of Jake, and roasted his head, not good meat, taste like sheep with the rot; but, sir, very hungry, eat anything.”

But perhaps no story from the Donner Party is as disturbing as that of Lewis Keseberg’s. The last person rescued from Truckee Lake in April 1847, Keseberg was purportedly discovered half-mad and surrounded by half-eaten bodies.

Other Donner Party members remember Keseberg, a German immigrant, as short-tempered and often cruel to his young wife. Rumors spread that he’d once comforted a young boy, only to kill him, hang him up in his cabin, and later eat him.

Wikimedia CommonsAs legend has it, German-born immigrant Lewis Keseberg was both abusive to his pregnant wife and ate some of the children while trapped in the mountains among the Donner Party. However, it was never proven.

Rescuers of the final relief claimed to have found him with a cauldron of human flesh. Allegedly, they offered him food but he demurred — and said he’d come to prefer eating people.

Other stories from the Donner Party reliefs are equally harrowing if less stomach-churning. One describes how Margaret Reed had to make a “Sophie’s Choice” concerning her children when rescue first arrived.

In journalist Ethan Rarick’s Desperate Passage: The Donner Party’s Perilous Journey West, the writer used both diaries and archaeological evidence to garner invaluable insight into the tragedy, with the Reed account convincing him the project was worth his time.

“One thing that led me to write the book is the moment when Margret Reed is walking out with her four children with the first rescue party,” he told U.S. News. “It becomes clear that Patty and Tommy [ages 8 and 3] will not be able to keep going. They’re going to have to be sent back.”

Wikimedia CommonsThe 28th page of Donner Party member Patrick Breen, recording his observations in February 1847. It reads: “Mrs Murphy said here yesterday that thought she would Commence on Milt. & eat him. I dont [sic] that she has done so yet, it is distressing.”

“The idea that another rescue party would get in before they would starve to death is pretty unlikely. Which means they’re probably going to die…She has to determine: Is she going to send back two of her children and try to go on? Is she going to go with them?”

“It”s like Sophie’s Choice, and she finally is convinced that she should go ahead with her two [older] children. As they say goodbye, Patty looks at her mother and says, ‘Well, Ma, if you never see me again, just do the best you can.'”

The Aftermath Of The Rescue And The Legacy Of The Donner Party To This Day

Though such accounts remain infamous even after nearly two centuries, actual stories of the Donner Party’s members eating each other are harder to come by. The survivors gave contradicting stories, and often retracted what they’d previously said. Trudeau, for example, later denied that he’d eaten anyone.

The firsthand accounts of rescuers and witnesses, however, along with the informed, researched opinions of journalists and historians after the fact, confidently state that as many as 21 people were eaten.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Donner Party Pioneer Statue memorial, erected in June 1918 and seen here in 2005. The plaque reads: “Virile to risk and find; Kindly withal and a ready to help. Facing the brunt of fate; Indomitable,—unafraid.”

But for Michael Wallis, who wrote The Best Land Under Heaven: The Donner Party in the Age of Manifest Destiny, the ghoulish aspects of the story have greatly overshadowed the bravery and resilience inherent in the accounts of the Donner Party’s survivors.

“Eating human flesh was a total, last resort,” Wallis explained. “People say, ‘Oh, those cannibals, how could they do that?’ I turn it around and say, ‘What would you do if you are a mother watching your children starve and freeze to death?'”

Wallis argues that when it came to the Donner Party, there was no black and white — only gray. The pioneers were desperate. Many of them had young children. Trapped in the mountains, they did what it took for their families to survive.

“Some of them never ever spoke of it again,” Wallis noted. “Some denied it, but not that many.”

After reading about the Donner Party, learn about the most incredible survival stories in history. Then, see some of the most incredible photos of the American frontier.