Image Source: www.familybydesign.com

Think of childhood. Not necessarily your childhood, but the idea of being a kid in general. What comes to mind? Playing? Curiosity? Imagination? Innocence?

These are all common, if not cliché, notions of what it means to be a child. You play, you learn, you imagine and you are kept sheltered from the dangers of the world for as long as possible. The adults in your life don’t want to rip you from that childhood naiveté; in fact, they love keeping you there. They want you to remain sweet and to remain untainted—to simply be a child.

That notion of childhood, however, is one we completely and utterly made up. French historian Philippe Ariès wrote perhaps the most widely read book on this very subject, Centuries of Childhood. Though much of the book is now criticized–in part, because some of his evidence was anchored in the adult clothing children wore in medieval portraiture–Ariès was the first to present childhood as a modern social construction, rather than a biological right.

Today, while distancing themselves from Ariès’ logic, many academics agree that the last few centuries of history have seen a major shift in how children are treated and how childhood itself is regarded.

Image Source: Amazon

The Routledge History of Childhood in the Western World, a recent compilation of essays from a range of scholars, presents a vast and detailed evolution of what we consider to be childhood–and, as the book is eager to point out, it seeks to finally put Ariès’ text to rest. Editor Paula S. Fass, a historian at UC Berkeley, notes the following in her introduction to the book:

“These essays clearly show that the ‘modern’ perspective on children as sexually innocent, economically dependent, and emotionally fragile whose lives are supposed to be dominated by play, school and family nurture, provides a very limited view of children’s lives in the modern western past. While some children did experience this kind of childhood, for the vast majority, it is quite literally only in the twentieth century that these have been enforced as both preferred and dominant.”

Fass continues to assert that our modern notion of childhood was forged during the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment, or The Age of Reason, spanned from about the 1620s to about the 1780s, and did a good job of shaking up the traditional, and often irrational, ideologies of the Middle Ages. Over the 17th and 18th centuries, the public made a relatively sharp turn toward scientific reason and advanced philosophical thought. As the products of a generation now enamored with reason, children were a big focal point for the many new forms of societal change.

Joshua Reynolds’ popular 18th century painting, “The Age of Innocence,” speaks to the emerging ideals about childhood. Image Source: Tate

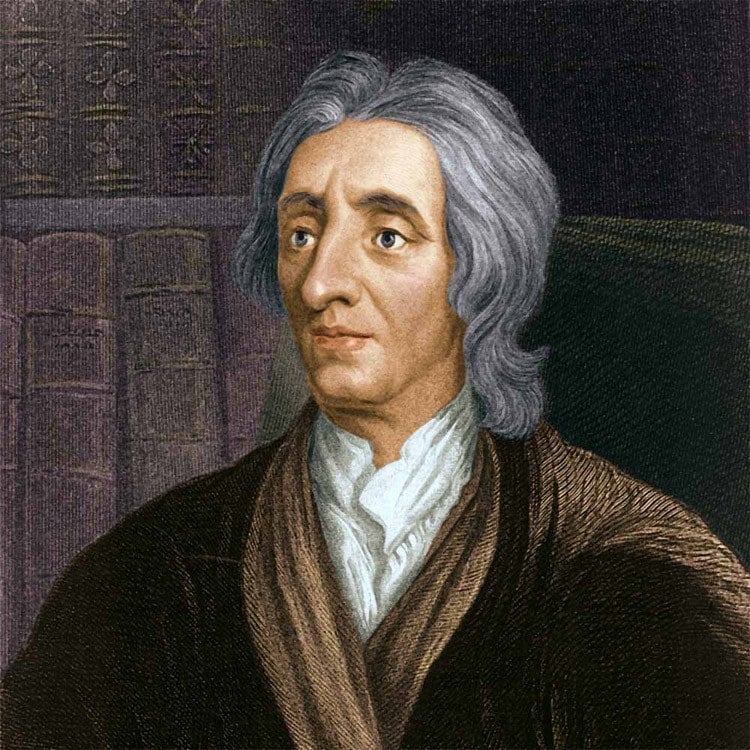

English philosopher and father of the Enlightenment John Locke published strong, controversial pieces on politics, religion, education, and liberty. An opponent of England’s entrenched, tyrannical monarchy, Locke quickly became famous among great thinkers with his 1689 publication of An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, in which he urged people to use reason as their guide, to think for themselves, and to understand their world via observation rather than religious dogma.

John Locke, Image Source: skepticism.org

By the time he published Some Thoughts Concerning Education in 1693, Locke’s ideas were highly regarded in educated circles. Flipping conventional wisdom about education on its head, Locke states that authoritarian teaching is counterproductive, suggesting, of children, that “all their innocent folly, playing, and childish actions are to be left perfectly free.” The goal was to make moral children, not scholars. Education should be enjoyable and sculpted around the needs of the individual child in order to make a productive, positive member of society.

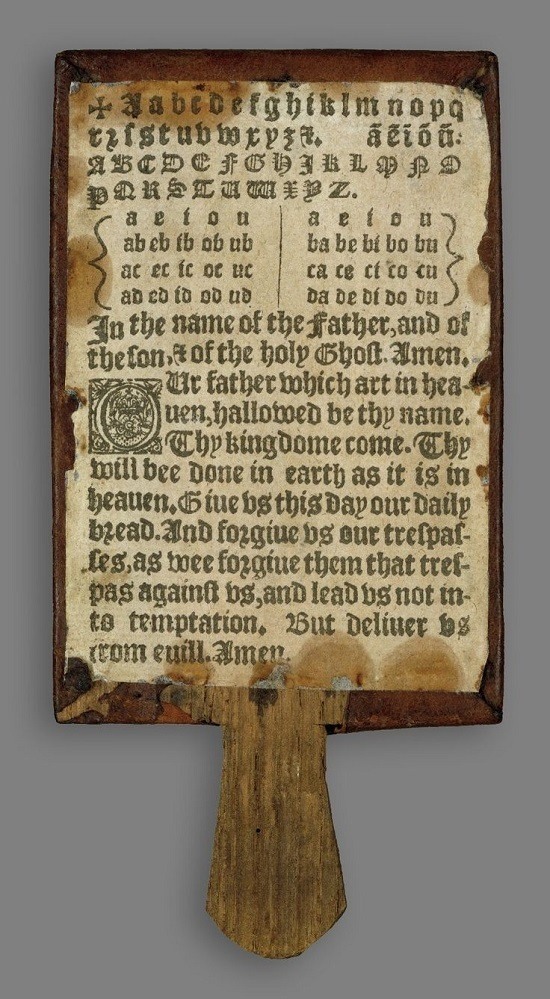

To understand just how revolutionary Locke’s ideology on education and children was, it needs to be put into context. In Locke’s time, forms of unstructured play or entertainment were considered a waste of time. As a result, throughout Locke’s life, the only “book” and learning tool specifically for children was the hornbook.

With a history that traces back to the 15th century, this “book” was actually a wooden paddle, traditionally inscribed with the alphabet, numbers from zero to nine, and a passage of scripture. And if that wasn’t fun enough, it had the dual purpose of being both a learning tool and a form of punishment if the child did something awful, like recite the alphabet incorrectly.

A hornbook from approximately 1630. Image Source: Pinterest

A woman holding a hornbook. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Furthermore, in Locke’s time, very little thought was given to a child’s rights. Especially if you didn’t have the money to care for a child, that child was simply a functional object, an extra worker. If the child wasn’t an extra hand, then they were an extra mouth to feed.

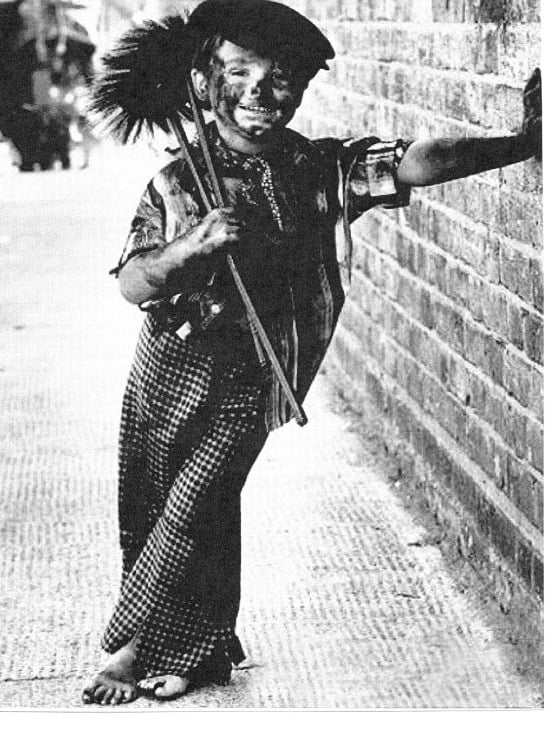

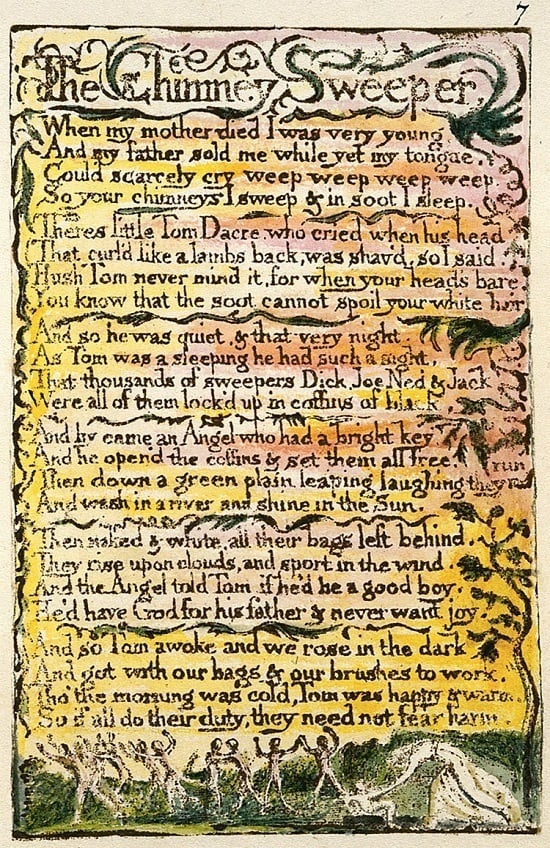

Perhaps nowhere is this more acutely evident than in the 200-year-long English tradition of child chimney sweeps, which really took off in the 1660s. Small boys between 4 and 10 years old from families of poverty were sold to master sweeps. Using their elbows, back and knees, the boys would climb up and down narrow chimneys to clean out the soot. These children were severely beaten, starved, disfigured, prone to serious health complications, and even liable to die as a result of getting permanently lodged in chimneys.

However, this “business model” remained popular because most were unsympathetic and no one bothered to create large brushes or rods until they were forced to, in 1875, when it finally became illegal to use children as chimney sweeps.

A master and apprentice chimney sweep. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

A child chimney sweep, Image Source: Western Civilization

William Blake’s 1789 poem, “The Chimney Sweeper,” from his book, Songs of Innocence. Image Source: Answers

Locke died in 1704 (long before the practice of using children as chimney sweeps), but in the following decades, the Enlightenment movement he helped create continued to move forward. Those he influenced continued to popularize his ideas. Literacy was also steadily on the rise (by 1800, 60-70 percent of adult men in England would be able to read, in comparison to 25 percent in 1600), and with literacy came both the ability to spread ideas more quickly and the demand for new publications. In 1620s, about 6,000 titles appeared. By 1710s, that number rose to nearly 21,000 and by the end of the century, it was over 56,000. As a result, religious texts and their medieval philosophies started to lose their monopoly over the written word and public mind.

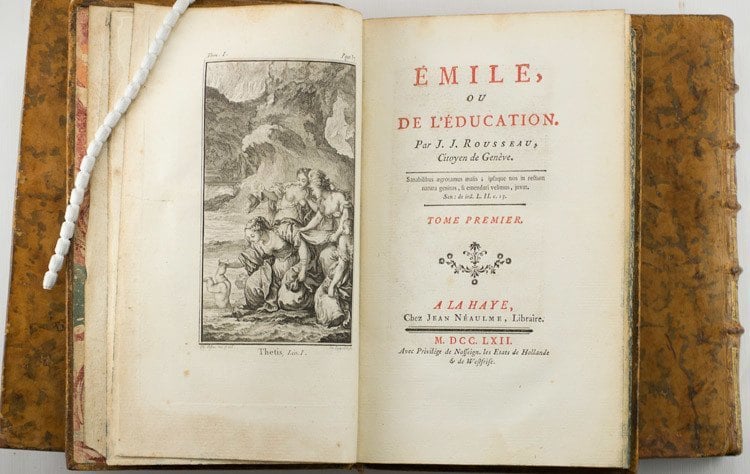

At this time, the next influential player in the creation of modern childhood stepped up. Greatly inspired by Locke, French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote a number of extremely popular works that had a profound influence on the continuation of the Enlightenment. In particular, Émile confronts the nature of education and man. It is from this writing that most of our modern notions surrounding the innate purity of children emerge. In contrast to the church’s views, Rousseau writes, “nature made me happy and good, and if I am otherwise, it is society’s fault.” Nature is, Rousseau believed, our greatest moral educator and children should focus on their bond with it.

Image Source: www.heritagebookshop.com

Whether from Locke, Rousseau or elsewhere in the Enlightenment, these notions of childhood largely go unquestioned today. Émile was published in 1762. Just over 250 years later, most of us adamantly believe that children have the right and freedom to be wild (within reason), explore nature, and enjoy a life unaffected by societal corruption. However, a century after Émile, we were still shoving sooty children down chimneys. And it wasn’t even a century ago that the United States fully put a stop to child labor, in 1938.

By that point, the Enlightenment had long come and gone. See, it takes time for these ideas we take for granted to spread through the classes and generations to be made “real.” As a result, today we sit secure in a concrete concept that separates us and our children from those of the Dark Ages, scarcely realizing that that concept is only as old as our grandparents.