Born out of England's need to quickly rebuild after World War II, Brutalist architecture is characterized by its divisive use of raw concrete and clunky design.

There's probably no architectural style of the last century that is more controversial than Brutalism.

Brutalist art started out as the practice of function over form and was viewed as a quick way to rebuild urban areas of Great Britain after World War II. It was primarily used for low-cost social housing, but it soon spread to institutional buildings, universities, government buildings, and libraries as well.

The name and style stem from the phrase "beton brut," which is French for "raw concrete." Despite its sparse, clunky design, Brutalism was introduced as a modern take on architecture — though few people welcomed its existence.

Brutalism Was Born Out Of Necessity

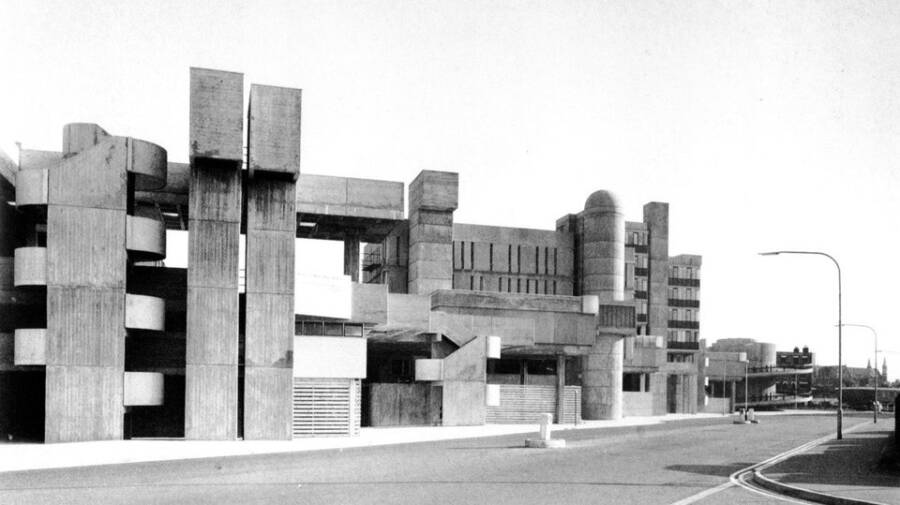

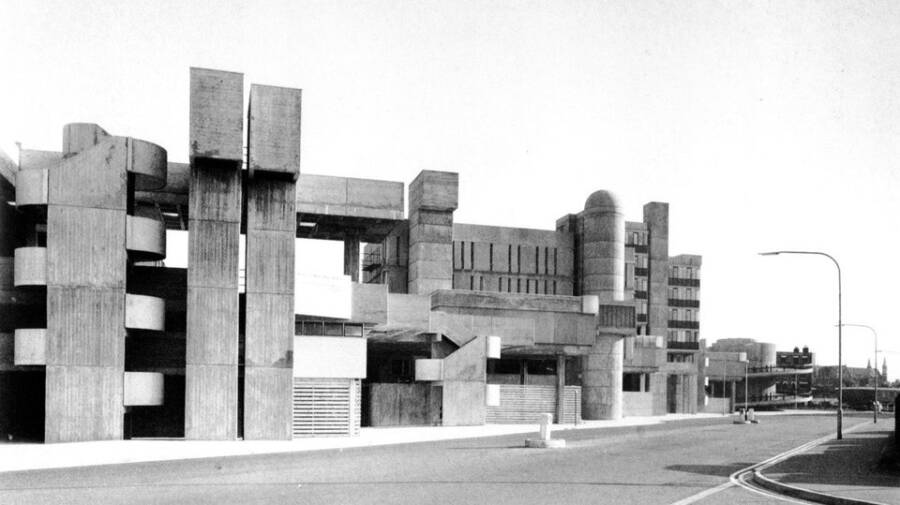

Iantomferry/Wikimedia Commons

East elevation of Unité d'habitation, in Marseille, France, is built in the style of Brutalism.

Brutalist art was a form born out of necessity. Material shortages in the post-World War II period demanded that concrete and brick, along with timber, were used in the majority of urban rebuilding. These elements would remain as they were found: unfinished and raw. This lack of material ultimately helped to define the style of Brutalist art.

The style is also based on the ideas of a Swiss-French architect named Le Corbusier, who believed that style should follow function.

A watchmaker-turned-artist, Le Corbusier (born Charles-Edouard Jeanneret) published the book Vers une Architecture in 1923, in which he famously declares, "A house is a machine for living in" and "a curved street is a donkey track; a straight street, a road for men."

Le Corbusier's articles proposed a new kind of architecture, one that would satisfy the demands of the post-war industry. Of course, there are many designers who contributed to the movement, such as British architects like Alison and Peter Smithson.

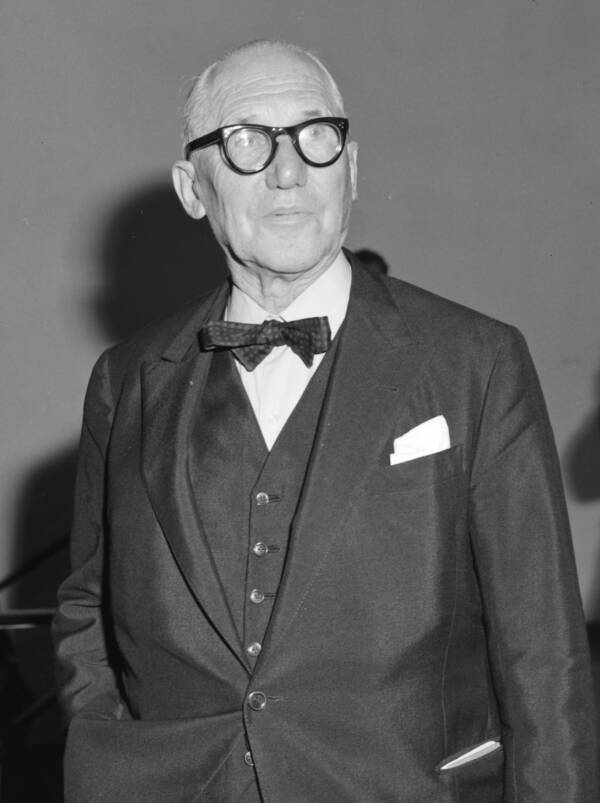

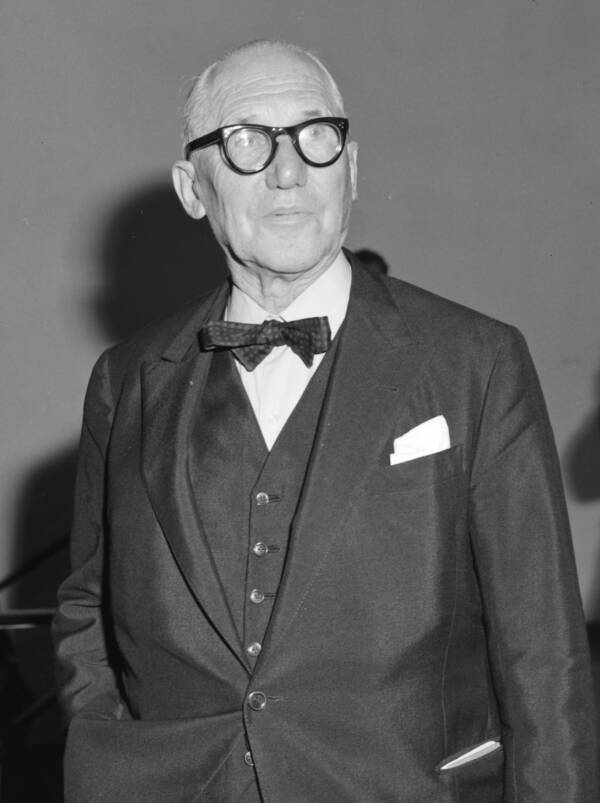

Joop van Bilsen / Anefo/Wikimedia Commons A portrait of Le Corbusier.

Described as cold and soulless, heavy and imposing, Brutalism is often associated with totalitarianism. In fact, many Brutalist structures do appear similar to buildings in Stalin's Soviet Union.

In an interview with Atlas Obscura, photographer and Brutalist enthusiast Ty Cole described the style's history in this way:

"First and foremost it was a cost-efficient building method. Thanks to the evolution of modernism, and a growing need for municipal buildings, universities, and low-income housing, there was an explosion of brutalist buildings. I think it tells us that the artists, including architects, wanted to express themselves in a more humanistic way, hence Le Corbusier's desire for architecture that felt like it was created by man."

Le Corbusier's social ideals and structural theories soon became reality. He designed Unité d'habitation buildings, which were modernist residential apartments that contained shops, restaurants, and even schools. He envisioned a whole city under one roof, surrounded by a park-like setting.

The most popular of these are the Unité d'habitation in Marseille, France, la Cité Radieuse, (also in Marseille) and Berlin's Unité.

The Style Divides Tastes

u/CJ105/redditTricorn Shopping Center in Portsmouth, United Kingdom.

Because Brutalism was something altogether different from previous architectural styles, it was polarizing when it was first introduced.

Prince Charles of Wales, for example, was Brutalist enemy number one. When he paid a visit to the Brutalist Birmingham Library over three decades ago, he purportedly likened it to a place where books are burned rather than put on loan. He also described the Brutalist Tricorn shopping center in Portsmouth, England designed by architect Rodney Gordon in the '60s as "a mildewed lump of elephant droppings."

Those who were fans of the style expressed their feelings just as strongly as those who were against it. Fans said of the Tricorn building, "There are as many ideas in a single Gordon building as there are in the entire careers of most architects," and that to behold the building was to feel oneself "in the presence of genius."

Tricorn was razed in 2004.

Polarizing, indeed. However, there are many examples of beauty and creativity within the style, and this is likely what has sparked its revival.

It's important to note that Brutalism and the "New Brutalism" of today resist a singular stylistic definition, as the term has come to be used for anything concrete. Brutalist buildings are not always concrete, but they do blatantly place the focus on their materials or forms.

The revival appears to be rooted in an appreciation (and the preservation of) still-standing Brutalist buildings.

Preservation Efforts Today

Fred Romero/Wikimedia CommonsCité radieuse, in Marseille, France.

In New York, Brutalist enthusiasts battled to save architect Paul Rudolph's Orange County Government Center from demolition — to limited success.

The city decided to only partially remove the eye-popping jumbled pile of blocks, whose "aesthetically lacking" exterior was countered by a politically consequential interior. Rudolph's atrium design forced government officials to interact with citizens, which the former often found to be an impediment to their work.

Meanwhile, in Boston, many administrative and academic buildings have been characterized as Brutalist, and a group of architects has attempted to reposition Brutalism through a discursive shift. The group aims to rebrand these structures as "Heroic" and reestablish the utilitarian ethos behind the style.

Now, there is #SOSBrutalism, a burgeoning campaign to save what supporters call our "beloved concrete monsters." The campaign is anchored to a growing database that currently contains over 1,900 Brutalist buildings. If you tag a building photo with #SOSBrutalism on social media, it will be checked to see if it's already included in the database.

Will Brutalist Architecture See A Revival?

Beyond physical preservation efforts, fans of Brutalism are attempting to cement the style into pop culture. They hope these efforts will help rebuild an appreciation of the style critics love to hate.

One way people have preserved Brutalist structures is through compromise. In the '90s, Ivor Smith's Brutalist Park Hill apartment block avoided destruction by having its interiors renovated. In addition, others have been granted UNESCO Heritage Site honors as standing tributes to Brutalism.

Builders are now softening many defining aspects of the style in both existing buildings and new construction. Concrete façades are sandblasted to create a more stone-like look or covered in stucco.

While no one knows exactly why the popularity of Brutalism has risen in recent years, GQ's Brad Dunning has a theory:

"Brutalism is the techno music of architecture, stark and menacing. Brutalist buildings are expensive to maintain and difficult to destroy. They can't be easily remodeled or changed, so they tend to stay the way the architect intended. Maybe the movement has come roaring back into style because permanence is particularly attractive in our chaotic and crumbling world."

Instead of destroying what may be easy to dislike on a superficial level, perhaps we should construct a deeper understanding of what the style attempted — and succeeded in — doing.

After this look at Brutalist art and architecture, check out the Ecuadorian cemetery in Tulcán that's decorated with life-sized whimsical topiaries. Then, explore some stunning examples of ancient architecture from around the world.