The March on Washington: why John F. Kennedy opposed it, why Martin Luther King Jr. almost didn't "have a dream," and everything else your history teacher never told you.

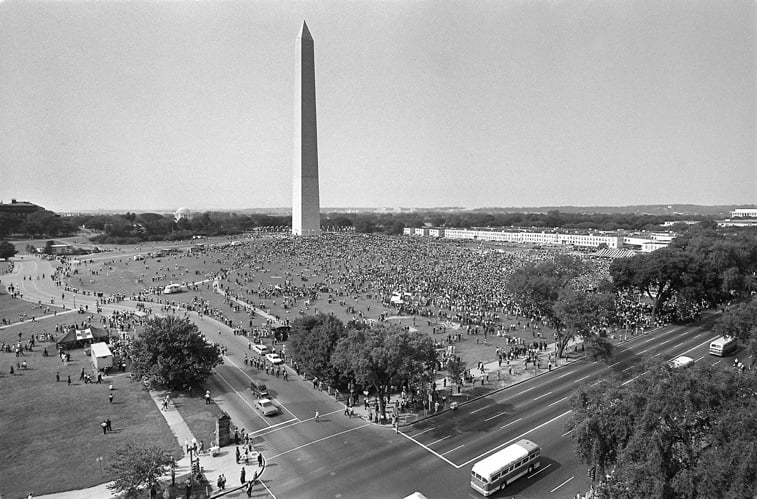

AFP/AFP/Getty ImagesMore than 200,000 civil right supporters gather for the March on Washington on August 28, 1963.

The 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom is probably best remembered as the event in which Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have A Dream” speech. But King almost didn’t even say those words that day. In fact, there’s much more to the story of this crucial civil rights moment than you learned in school.

1. A Gay Quaker Organized The March On Washington In Just Two Months

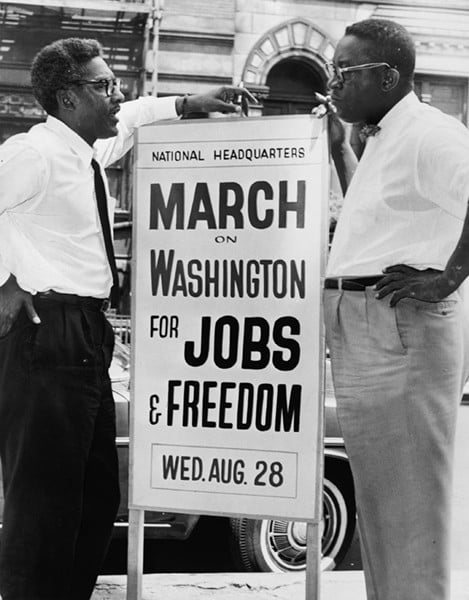

Wikimedia Commons Bayard Rustin (left) standing with a sign announcing the march.

The idea for the March on Washington came from A. Phillip Randolph, a prominent civil rights leader at the time. He had dreamed of having the march since 1941, when he threatened President Roosevelt with a march of 100,000 people to protest military segregation.

Eventually, in 1962, Randolph asked civil rights leader Bayard Rustin to organize the March on Washington. It wasn’t until July of 1963, when Randolph and other civil rights leaders met to make the march official, that Rustin could start planning in earnest. The march was scheduled for August 28, giving Rustin only eight weeks to put the enormous event together.

Though Rustin was an experienced activist, some opposed his role in the march because he was gay, and as a Quaker, was jailed as a conscientious objector during World War 2.

Event planners worried these facts could be used to discredit the march, but Randolph and King, who had worked with Rustin on other demonstrations such as the Montgomery bus boycott, insisted on keeping him on as the head organizer.

2. President Kennedy Didn’t Support The March On Washington

Wikimedia CommonsJohn F. Kennedy (eighth from left) meets with some of the march’s organizers including Martin Luther King Jr. (third from left), John Lewis (fourth from left), Whitney Young (second from right), and A. Philip Randolph (seventh from left).

Though President John F. Kennedy had recently introduced his Civil Rights Act (which would pass in 1964, thanks in large part to the march’s success), he tried to stop the March on Washington from happening. This opposition came not from a general dislike of the march, but from concerns that such a large demonstration might lead to violence and thus dissuade Congress from passing his Civil Rights Act.

With these fears in mind, in June 1963 Kennedy met with the “Big Six” civil rights leaders (King, Randolph, James Farmer, John Lewis, Roy Wilkins, and Whitney Young) and tried to get them to cancel the march. They refused.

Seeking compromise, Kennedy successfully imposed limits on the march: He reduced the number of attendees allowed; outlawed any signs not pre-approved; demanded that it take place on a weekday, and that everyone show up in the morning and disperse by nightfall.

3. The March Shut Out The Civil Rights Movement’s Female Leadership

Wikimedia CommonsDaisy Bates (left) and Odetta Holmes.

While the Civil Rights Movement actively campaigned for equality, that principle didn’t seem to fully apply when it came to selecting who could speak during the official ceremony. Though singer Josephine Baker spoke briefly before the official program began, women did not speak at the Lincoln Memorial podium. Organizers didn’t even invite Dorothy Height, leader of the National Council of Negro Women, to make a speech.

This decision appeared to be systematic. By Cambridge Movement leader Gloria Richardson’s own account, she — one of the few women originally slated to speak at the rally — had her microphone taken away as she greeted the audience.

The exclusion continued even after the event, when male leaders went to visit JFK and left critical female activists including Rosa Parks behind.

Many women who had campaigned tirelessly for their cause recognized the slight all too well. “We grinned; some of us,” activist Anna Arnold Hedgeman recalled of that day, “as we recognized anew that Negro women are second-class citizens in the same way that white women are in our culture.”

4. The March On Washington Didn’t Just Focus On Civil Rights

Wikimedia CommonsThe crowd gathered beneath the Washington Monument.

While popularly remembered as a critical success in the civil rights story, the march hardly confined itself to the question of civil rights alone. That truth can be found in the event’s very name, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Indeed, the official goals of the march were just as much about civil rights — in terms of political and social freedoms — as they were about workplace equality for all Americans.

When translated to concrete demands, this equality meant the desegregation of all schools, comprehensive civil rights legislation that gave black people access to decent housing and protected their right to vote, but also a minimum wage of two dollars and federal programs that would train and place unemployed workers — both both black and white.

5. Many Celebrities Attended The March And Supported The Movement

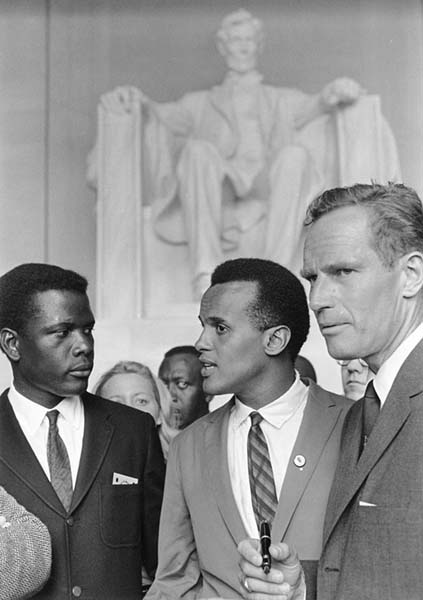

Wikimedia CommonsFrom left: Charlton Heston, James Baldwin, and Marlon Brando.

While many cite the names of civil rights leaders when recalling the march’s big names, many artists and celebrities also participated in the March on Washington.

Hollywood had a large contingent at the rally: Actor Charlton Heston came with legendary director Joseph Mankiewicz, and stars like Marlon Brando, Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, and Paul Newman composed part of the 250,000-person crowd. On the stage, actors Ruby Dee and her husband, Ossie Davis, served as the demonstration’s emcees.

Wikimedia CommonsFrom left: Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, and Charlton Heston.

Outside of Hollywood, Jackie Robinson brought his young son, David, to the march. Iconic writer James Baldwin came out, along with singer Sammy Davis Jr. and folk legend Bob Dylan, who performed a song with Joan Baez.

6. The Organizers Weren’t A Wholly United Front

Wikimedia CommonsMartin Luther King Jr. (second from left in front row) leads the March On Washington.

The march’s official leadership consisted of the most powerful and influential men in the civil rights movement: Jim Farmer, co-founder of the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE); Martin Luther King Jr., president of the Southern Christian Leadership Council; current member of the House of Representatives John Lewis, who at the time of the march was chairman of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) at only 23 years old; Roy Wilkins, executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People; Whitney Young, executive director of the National Urban League, which sought to end employment discrimination; and A. Phillip Randolph, who founded the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the Negro American Labor Council.

However, none of them could agree on what the goals of the march should be: Wilkins would not participate in any act of civil disobedience, nor would he criticize the Kennedy administration, while the more radical CORE and SNCC wanted to use the opportunity to protest the administration’s lack of substantial action on civil rights issues. Meanwhile, Randolph and King were especially interested in furthering economic causes, like raising the minimum wage.

Eventually, the organizers were able to come to a moderate agreement that addressed labor concerns as well as civil rights concerns, and, moreover, kept all the leaders invested and cooperative.

7. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have A Dream” Speech Happened Spontaneously

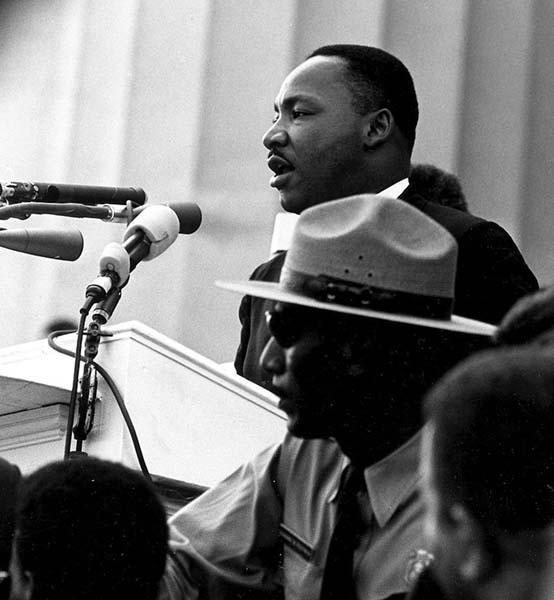

Wikimedia CommonsMartin Luther King Jr. giving his famous speech.

One of the nation’s most widely-revered speeches happened extemporaneously. King spoke last that day, as advisors suggested that news crews might leave if he spoke early on or midway through.

And when he stepped to the podium toward the end of the official program, King didn’t even have his “dream” on his notes. Indeed, it wasn’t until singer Mahalia Jackson stood up and called out from the audience, “Tell them about the dream, Martin!” that King pushed his notes aside and delivered one of history’s most significant speeches.

Next, check out ten fascinating Martin Luther King Jr. facts you’ve never heard before. Then, see 20 inspiring photos from the March on Washington.